![]()

PART I

Discovering the Chasm

![]()

Introduction

If Mark Zuckerberg Can Be a Billionaire

There is a line from a song in the musical A Chorus Line: “If Troy Donahue can be a movie star, then I can be a movie star.” Every year one imagines hearing a version of this line reprised in high-tech start-ups across the country: “If Mark Zuckerberg can be a billionaire . . .” For indeed, the great thing about high tech is that, despite numerous disappointments, it still holds out the siren lure of a legitimate get-rich-quick opportunity.

This is the great attraction. And yet, as the Bible warns, while many are called, few are chosen. Every year millions of dollars—not to mention countless work hours of our nation’s best technical talent—are lost in failed attempts to join this kingdom of the elect. And oh what wailing then, what gnashing of teeth!

“Why me?” cries out the unsuccessful entrepreneur. Or rather, “Why not me?” “Why not us?” chorus his equally unsuccessful investors. “Look at our product. Is it not as good—nay, better—than the product that beat us out? How can you say that Salesforce is better than RightNow, LinkedIn is better than Plaxo, Akamai’s content delivery network is better than Internap’s, or that Rackspace’s cloud is better than Terremark’s?” How, indeed? For in fact, feature for feature, the less successful product is often arguably superior.

Not content to slink off the stage without some revenge, this sullen and resentful crew casts about among themselves to find a scapegoat, and whom do they light upon? With unfailing consistency and unerring accuracy, all fingers point to—the vice president of marketing. It is marketing’s fault! Salesforce outmarketed RightNow, LinkedIn outmarketed Plaxo, Akamai outmarketed Internap, Rackspace outmarketed Terremark. Now we too have been outmarketed. Firing is too good for this monster. Hang him!

While this sort of thing takes its toll on the marketing profession, there is more at stake in these failures than a bumpy executive career path. When a high-tech venture fails, everyone goes down with the ship—not only the investors but also the engineers, the manufacturers, the president, and the receptionist. All those extra hours worked in hopes of cashing in on an equity option—all gone.

Worse still, because there is no obvious reason why one venture succeeds and the next one fails, the sources of capital to fund new products and companies become increasingly wary of investing. Interest rates go up, valuations go down, and the willingness to entertain venture risk abates. Meanwhile, Wall Street just emits another deep sigh. It has long been at wit’s end when it comes to high-tech stocks. Despite the efforts of some of its best analysts, these stocks are traditionally misvalued, often spectacularly so, and therefore exceedingly volatile. It is not uncommon for a high-tech company to announce even a modest shortfall in its quarterly projections and incur a 30 percent devaluation in stock price on the following day of trading. As the kids like to say, What’s up with that?

There are, however, even more serious ramifications. High-tech innovation and marketing expertise are two cornerstones of the U.S. strategy for global competitiveness. We will never have the lowest cost of labor or raw materials, so we must continue to exploit advantages further up the value chain. If we cannot at least learn to predictably and successfully bring high-tech products to market, our countermeasures against the onslaught of commoditizing globalization will falter, placing our entire standard of living in jeopardy.

With so much at stake, the erratic results of high-tech marketing are particularly frustrating, especially in a society where other forms of marketing appear to be so well under control. Elsewhere—in cars or consumer electronics or apparel—we may see ourselves being outmanufactured, but not outmarketed. Indeed, even after we have lost an entire category of goods to offshore competition, we remain the experts in marketing these goods to U.S. consumers. Why haven’t we been able to apply these same skills to high tech? And what is it going to take for us to finally get it right?

It is the purpose of this book to answer these two questions in considerable detail. But the short answer is as follows: Our default model for how to develop a high-tech market is almost—but not quite—right. As a result, our marketing ventures, despite normally promising starts, drift off course in puzzling ways, eventually causing unexpected and unnerving gaps in sales revenues, and sooner or later leading management to undertake some desperate remedy. Occasionally these remedies work out, and the result is a high-tech marketing success. (Of course, when these are written up in retrospect, what was learned in hindsight is not infrequently portrayed as foresight, with the result that no one sees how perilously close to the edge the enterprise veered.) More often, however, the remedies either flat-out fail, and a product or a company goes belly-up, or they progress after a fashion to some kind of limp but yet-still-breathing half-life, in which the company has long since abandoned its dreams of success and contents itself with once again making payroll.

None of this is necessary. We have enough high-tech marketing history now to see where our model has gone wrong and how to fix it. To be specific, the point of greatest peril in the development of a high-tech market lies in making the transition from an early market dominated by a few visionary customers to a mainstream market dominated by a large block of customers who are predominantly pragmatists in orientation. The gap between these two markets, all too frequently ignored, is in fact so significant as to warrant being called a chasm, and crossing this chasm must be the primary focus of any long-term high-tech marketing plan. A successful crossing is how high-tech fortunes are made; failure in the attempt is how they are lost.

For the past two decades, I, along with my colleagues at the Chasm Group, Chasm Institute, and TCG Advisors, have watched countless companies struggle to maintain their footing during this difficult period. It is an extremely difficult transition for reasons that will be summarized in the opening chapters of this book. The good news is that there are reliable guiding principles. The material that follows has been refined over hundreds of consulting engagements focused on bringing products and companies into profitable and sustainable mainstream markets. The models presented here have been tested again and again and have been found effective. The chasm, in short, can be crossed.

That said, like a hermit crab that has outgrown its shell, the company crossing the chasm must scurry to find its new home. Until it does, it will be vulnerable to all kinds of predators. This urgency means that everyone in the company—not just the marketing and sales people—must focus all their efforts on this one end until it is accomplished. Chapters 3 through 7 set forth the principles necessary to guide high-tech ventures during this period of great risk. This material focuses primarily on marketing, because that is where the leadership must come from, but I ultimately argue in the Conclusion that leaving the chasm behind requires significant changes throughout the high-tech enterprise. The book closes, therefore, with a call for additional new strategies in the areas of finance, organizational development, and R&D.

This book is unabashedly about and written specifically for marketing within high-tech enterprises. But high tech can be viewed as a microcosm of larger industrial sectors. In this context, the relationship between an early market and a mainstream market is not unlike the relationship between a fad and a trend. Marketing has long known how to exploit fads and how to develop trends. The problem, since these techniques are antithetical to each other, is that you need to decide which one—fad or trend—you are dealing with before you start. It would be much better if you could start with a fad, exploit it for all it was worth, and then turn it into a trend.

That may seem like a miracle, but that is in essence what high-tech marketing is all about. Every truly innovative high-tech product starts out as a fad—something with no known market value or purpose but with “great properties” that generate a lot of enthusiasm within an “in crowd” of early adopters. That’s the early market.

Then comes a period during which the rest of the world watches to see if anything can be made of this; that is the chasm. If in fact something does come out of it—if a value proposition is discovered that can be predictably delivered to a targetable set of customers at a reasonable price—then a new mainstream market segment forms, typically with a rapidity that allows its initial leaders to become very, very successful.

The key in all this is crossing the chasm—performing the acts that allow the first shoots of that mainstream market to emerge. This is a do-or-die proposition for high-tech enterprises; hence it is logical that they be the crucible in which “chasm theory” is formed. But the principles can be generalized to other forms of marketing, so for the general reader who can bear with all the high-tech examples in this book, useful lessons may be learned.

One of the most important lessons about crossing the chasm is that the task ultimately requires achieving an unusual degree of company unity during the crossing period. This is a time when one should forgo the quest for eccentric marketing genius in favor of achieving an informed consensus among mere mortals. It is a time not for dashing and expensive gestures but rather for careful plans and cautiously rationed resources—a time not to gamble all on some brilliant coup but rather to focus everyone on pursuing a high-probability course of action and making as few mistakes as possible.

One of the functions of this book, therefore—and perhaps its most important one—is to open up the logic of marketing decision making during this period so that everyone on the management team can participate in the market development process. If prudence rather than brilliance is to be our guiding principle, then many heads are better than one. If market forces are going to be the guiding element in our strategy—and most organizations insist this is their goal—then their principles must be accessible to all the players, and not, as is sometimes the case, reserved to an elect few who have managed to penetrate their mysteries.

Crossing the Chasm, therefore, is written for the entire high-tech community—for everyone who is a stakeholder in the venture, engineers as well as marketers, and financiers as well. All must come to a common accord if the chasm is to be safely negotiated. And with that thought in mind, let us turn to chapter 1.

![]()

1

High-Tech Marketing Illusion

When this book was originally drafted in 1989, I drew on the example of an electric car as a disruptive innovation that had yet to cross the chasm. Indeed at that time there were only a few technology enthusiasts retrofitting cars with alternative power supplies. When I revised it extensively in 1999, once again I drew on the same example. GM had just released an electric vehicle, and all the other manufacturers were making noise. But the market yawned instead. Now it is 2013, and once again we are talking about the market for electric vehicles. This time the vendor in the spotlight is Tesla, and the vehicle getting the most attention is their Model S sedan.

Stepping back a bit from the cool factor, let’s assume these cars work like any other, except they are quieter and better for the environment. Now the question is: When are you going to buy one?

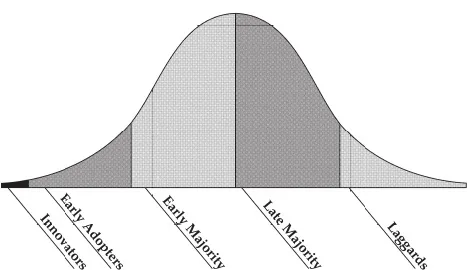

The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

Your answer to the preceding question will tell a lot about how you relate to the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, a model for understanding the acceptance of new products. If your answer is “Not until hell freezes over,” you are probably a very late adopter of technology, what we call in the model a laggard. If your answer is “When I have seen electric cars prove themselves and when there are enough service stations on the road,” you might be a middle-of-the-road adopter, or in the model, the early majority. If you say, “Not until most people have made the switch and it becomes really inconvenient to drive a gasoline car,” you are probably more of a follower, a member of the late majority. If, on the other hand, you want to be the first one on your block with an electric car, you are apt to be an innovator or an early adopter.

In a moment we are going to take a look at these labels in greater detail, but first we need to understand their significance. It turns out our attitude toward technology adoption becomes significant—at least in a marketing sense—any time we are introduced to products that require us to change our current mode of behavior or to modify other products and services we rely on. In academic terms, such change-sensitive products are called discontinuous or disruptive innovations. The contrasting term, continuous or sustaining innovations, refers to the normal upgrading of products that does not require us to change behavior.

For example, when Warby Parker promises you better-looking eyeglasses, that is a continuous innovation. You still are wearing the same combination of lenses and frames, you just look cooler. When Ford’s Fusion promises better mileage, when Google Gmail promises you better integration with other Google apps, or when Samsung promises sharper and brighter TV pictures across bigger and bigger screens, these are all continuous innovations. As a consumer, you don’t have to change your ways in order to take advantage of these improvements.

On the other hand, if the Samsung were a 3-D TV, it would be incompatible with normal viewing, requiring you to don special glasses to get the special effects. This would be a discontinuous innovation because you would have to change your normal TV-viewing behavior. Similarly if the new Gmail account were to be activated on a Google Chrome notebook running Android, it would be incompatible with most of today’s software base, which runs under either Microsoft or Apple operating systems. Again, you would be required to seek out a whole new set of software, thereby classifying this too as a discontinuous innovation. Or if the new Ford Fusion is the Energi model, which uses electricity instead of gasoline, or if the new sight-improvement offer were Lasik surgery rather than eyeglasses, then once again you would have an offer incompatible with the infrastructure of supporting components otherwise available. In all these cases, the innovation demands significant changes by not only the consumer but also the infrastructure of supporting businesses that provide complementary products and services to round out the complete offer. That is how and why such innovations come to be called discontinuous.

Between continuous and discontinuous lies a spectrum of demands for behavioral change. Contact lenses, unlike Lasik surgery, do not require a whole new infrastructure, but they do ask for a whole new set of behaviors from the consumer. Internet TVs do not require any special viewing glasses, but they do require the consumer to be “digitally competent.” Microsoft’s Surface tablet, unlike the Chrome notebook, is compatible with the installed base of Microsoft applications, but its “tiles” interface requires users to learn a whole new set of conventions. And Ford’s hybrid Fusion, unlike its Energi model, can leverage the existing infrastructure of gas stations, but it does require learning new habits for starting and running the car. All these, like the special washing instructions for certain fabrics, the special street lanes reserved for bicycle riders, the special dialing instructions for calling overseas, represent some new level of demand on the consumer to absorb a change in behavior. That’s the price of modernization. Sooner or later, all businesses must make these demands. And so it is that all businesses can profit by lessons from high-tech industries.

Whereas other industries introduce discontinuous innovations only occasionally and with much trepidation, high-tech enterprises do so routinely and as confidently as a born-again Christian holding four aces. From their inception, therefore, high-tech industries have needed a marketing model that coped effectively with this type of product introduction. Thus the Technology Adoption Life Cycle became central to the entire sector’s approach to marketing. (People are usually amused to learn that the original research that gave rise to this model was done on the adoption of new strains of seed potatoes among American farmers. Despite these agrarian roots, however, the model has thoroughly transplanted itself into the soil of Silicon Valley.)

The model describes the market penetration of any new technology product in terms of a progression in the types of consumers it attracts throughout its useful life:

TECHNOLOGY ADOPTION LIFE CYCLE

As you can see, we have a bell curve. The divisions in the curve are roughly equivalent to where standard deviations would fall. That is, the early majority and the late majority fal...