eBook - ePub

From Foragers to Farmers

Papers in Honour of Gordon C. Hillman

Ehud Weiss, Andrew S. Fairbairn

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 298 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

From Foragers to Farmers

Papers in Honour of Gordon C. Hillman

Ehud Weiss, Andrew S. Fairbairn

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This volume celebrates the career of archaebotanist Professor Gordon C. Hillman. Twenty-eight papers cover a wide range of topics reflecting the great influence that Hillman has had in the field of archaeobotany. Many of his favourite research topics are covered, the body of the text being split into four sections: Personal reflections on Professor Hillman's career; archaeobotanical theory and method; ethnoarchaeological and cultural studies; and ancient plant use from sites and regions around the world. The collection demonstrates, as Gordon Hillman believes, that the study of archaebotany is not only valuable, but vital for any study of humanity.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

From Foragers to Farmers è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a From Foragers to Farmers di Ehud Weiss, Andrew S. Fairbairn in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Social Sciences e Archaeology. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

Social SciencesCategoria

Archaeology17

Glimpsing into a hut: The economy and Society of Ohalo II’s inhabitants

Introduction

Archaeologists using remnants of prehistoric sites to reconstruct our ancestors’ way of life face a Herculean task. In most cases, the unearthed wastes are a remarkably small fraction of the residents’ material culture, and investigators must reconstruct the whole picture from a limited number of fragments. One of Gordon Hillman’s great contributions to the field of archaeobotany and to us – his students – is his approach of restoring the picture by deducing information from many related fields of research. In Gordon’s way, the pieces collected are woven together via well-reasoned interpretations, a process that aims at providing readers with an understanding of how this interpretation was achieved. In this chapter, I will summarise several years of archaeobotanical research on the inhabitants of Ohalo II, an Upper Palaeolithic site in Israel. The goal of analysing the site’s plant remains was a search for the face of these people and to reconstruct their way of life in the way Gordon taught us.

Beyond the many hours of formal lectures and discussions during my studies on the third floor and the imbibing of major quantities of scientific thought and information, it was Gordon’s enthusiasm that still inspires me, among others, to live archaeobotany. With sparkling eyes, he discussed an issue, explained a procedure, a plant’s anatomy or morphology, but above all – he exuded self-confidence that archaeobotany is indeed possible and even wondrous. His spirit percolates slowly and inexorably into the souls and minds of his students.

For me, it is a special honor and pleasure to dedicate this paper to Gordon. My Ohalo II archaeobotanical research started in Professor Mordechai Kislev’s laboratory, but various issues were also intensively discussed with Gordon, especially during my stay with him during the academic year of 1998. It was Gordon who urged me to go back to Israel after I did my MSc with him at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, and to investigate the Ohalo II material as my PhD project. I therefore find it appropriate to review here our current view of the hunter-gatherer society of the Upper Jordan Valley, 23,000 years ago.

Ohalo II: The site, its excavation and preservation

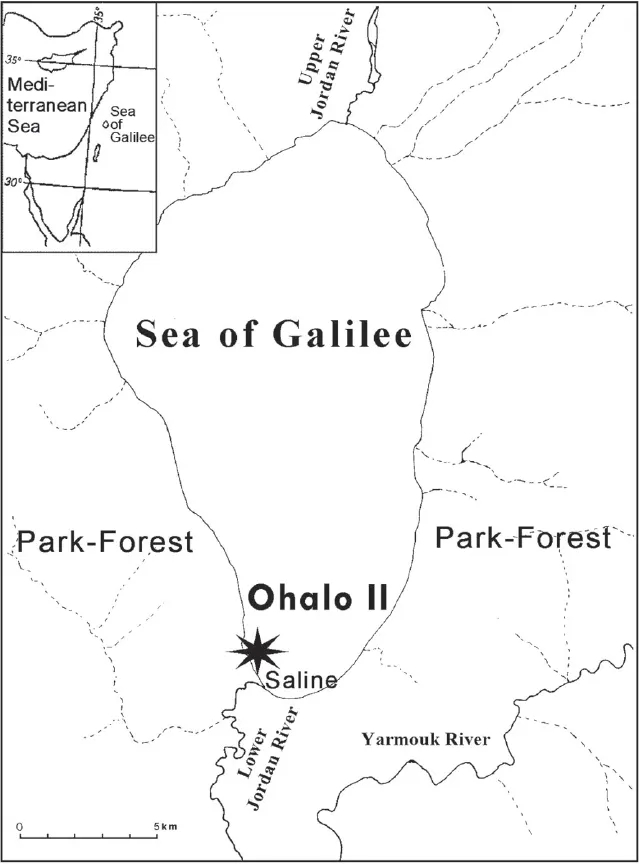

Ohalo II is located on the southwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret), on the Israel side of the Rift Valley (Figure 17.1). It is a submerged, late Upper Paleolithic (locally termed Early Epipalaeolithic) site, radiocarbon dated to 23,000 cal BP (Nadel 2002, Nadel, Carmi, and Segal 1995). Ohalo II covers more than 2000m2 (0.2 hectare) and its findings include the remains of six brush huts, hearths and a human grave; it is reconstructed as a hunter-gatherer fishing camp. It was occupied during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a period of cold, dry climate when ice sheets covered parts of North America and Europe (Bard et al. 2000, Bar-Mathews, Ayalon and Kaufman 1997, Baruch and Bottema 1991, Baruch and Bottema 1999).

Since the discovery of Ohalo II in 1989, six excavation seasons have been conducted by Dr Dani Nadel of Haifa University. Three successive seasons were carried out immediately (1989–1991) when the Lake Kinneret water level dropped as a result of severe drought, exposing the site on the expanded beach perimeter. The rainfall of winter 1991 was particularly high, resubmerging the site for several years and rendering fieldwork difficult. However in 1999–2001, another set of severe droughts and heavy pumping from the lake exposed Ohalo II once more, making possible three more seasons of excavation.

The archaeological site is situated on the bedrock of the salty Lisan formation, 212m below mean sea level (msl) (Belitzky and Nadel 2002, Tsatskin and Nadel 2003). The Lisan Formation was created by lacustrine sediments of the salty Lake Lisan, dated from 70,000–15,000 cal BP. In ~25,000 cal BP, the lake approached its maximum elevation for this period, 164m below msl; it stretched approximately from the present-day Sea of Galilee in the north to Hazeva, Arava Valley, in the south. At ~23,000–19,000 cal BP, the lake had dropped again to ~270m below msl (Bartov et al. 2002).

Figure 17.1. Location of Ohalo II on the southern shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel, and a general reconstruction of nearby habitats where plants were gathered.

The huts of Ohalo II were dug into the Lisan Formation bedrock that accumulated over the period of high lake elevation and that were subsequently exposed on the shores of the newly formed Sea of Galilee. Before building the walls of these huts, the site inhabitants dug shallow, 20–30cm deep, oval depressions into the soft bedrock. They then built a wall along the perimeter of the depression with local trees such as tamarisk (Tamarix), willow (Salix), and oak (Quercus). The skeleton of the walls was formed from thick branches of these trees, which was later covered with local grasses and smaller, leaf-bearing branches. The walls were probably tilted inward in order to touch one another and form a dome-like structure. This simple design requires no central support and, in fact, no postholes were found in the huts or around them (Nadel and Werker 1999).

Ohalo II is a rich site. There is no other Levantine Upper Palaeolithic site with such well-preserved huts, hearths, a grave, and large quantities of remains. These include flint and ground stone tools, a large faunal spectrum (mammals, birds, rodents, fish, mollusks) and a rich plant assemblage (Bar-Yosef Mayer 2002, Belmaker 2002, Belmaker, Nadel, and Tchernov 2001, Kislev, Nadel, and Carmi 1992, Nadel 2002, Nadel et al. 1994, Rabinovich 1998, Rabinovich 2002, Rabinovich and Nadel 1994–5, Simmons 2002, Simmons and Nadel 1998).

The rise in water level, which sealed Ohalo II after its abandonment, is probably the major reason for the site’s excellent preservation (Belitzky and Nadel 2002, Nadel et al. 2002, Tsatskin and Nadel 2003). Nevertheless, the preservation seems to have involved two steps. The first was charring by fire, the mode of preservation for most of the archaeobotanical assemblage. The second is coverage by the rising lake water, which evidently took place after the site was abandoned. We have no evidence to indicate whether the rising water was the reason for abandonment or if there were other independent causes. Nevertheless, the rise in lake level followed site abandonment, with the silt and clay being deposited over an already unoccupied site and sealing the archaeological layers. This combination of charring and of remaining undisturbed under several meters of lake water helped to reinforce the site’s preservation. In addition, it is important to note that Ohalo II is a single-period site and that its preservation under the water for all these years prevented damage by various agents well-known at other sites. These include freeze-and-thaw and wet-and-dry cycles, animal burrowing, ditch digging, and so forth (Weiss 2002).

The plant assemblage

Although only a fraction of the samples taken from the site have been analysed, some 90,000 charred seeds and fruits, representing 142 taxa, have already been identified. Among them only 152 seeds are waterlogged. This data-set is larger than that of any contemporary site (Kislev, Nadel and Carmi 1992, Kislev and Simchoni 2002, Kislev, Simchoni, and Weiss 2002, Nadel et al. 2003, Simchoni 1998, Weiss 2002).

In order to evaluate the level of preservation manifested at Ohalo II, we will employ several measures. These include the total quantity of finds (including those still unidentified), the number of different taxa and different families, the percentage of seeds identified as belonging to a single species, the percentage of seeds identified as belonging to 2 alternative species, the percentage of seeds identified as belonging to a genus, and the percentage of seeds identified as belonging to the above-genus level (two alternative genera or a family, Table 17.1). A last measure, which we do not quantify, is the preservation of delicate morphological features. As accepted in the archaeobotanical literature, several plants were identified to a species level but with a question mark, which indicates a slightly lower confidence level in their identification. To make Table 17.1 clearer, we did not refer to the few question marks when attributing the species to groups.

Plant identification level is extremely important for environmental reconstruction. Since all plant species have their own requirements, including growing conditions, climate, soil, solar radiation and so on, their identification allows evaluation of the site’s ecological surroundings. Moreover, plants that grow under similar conditions can be found together in particular ecological niches. By listing the plants found in an archaeological site, present-day geobotanical data for these species may be used for reconstructing the prehistoric ecosystem around the site. Therefore, for confident environmental reconstructions, only plants identified at the single species level should be used. In some cases, when the identification is restricted to two species sharing the same habitat, these too may be used for environmental reconstruction. In Ohalo II, some 100 taxa were found suitable for representing their habitat (Kislev, Nadel, and Carmi 1992, Kislev and Simchoni 2002, Kislev, Simchoni, and Weiss 2002, Nadel et al. 2003, Simchoni 1998, Weiss 2002).

Number of finds | 90,341 |

Number of taxa | 142 |

Number of families | 33 |

Single species identification | 82 (~58%) |

Two closely related species | 23 (~16%) |

Genus level | 22 (~15%) |

Above-genus level | 15 (~11%) |

Table 17.1. Measures of the level of preservation of Ohalo II finds.

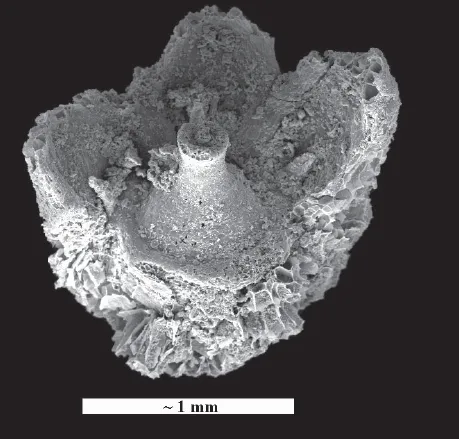

Figure 17.2. Egyptian sea-blite (Suaeda aegyptiaca) flower, side and half-up view. Of the original five perianth leaves, three are preserved, holding the stamens’ filament at their base. In the middle of the flower is an elongated pear-like ovary, with a shallow depression on its top. A very short style emerges from the bottom of the depression and is split into three stigmas.

The last measure, which is the first to be discovered when an assemblage is initially examined under the microscope, is the appearance of delicate morphological features. This category is hard to quantify, but may be clearly illustrated in few pictures, taken under the SEM (Figures 17.2–17.4). The Egyptian sea-blite flower (Suaeda aegyptiaca, Figure 17.2), the premat...