eBook - ePub

The Victorian House

Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

Judith Flanders

This is a test

Condividi libro

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

The Victorian House

Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

Judith Flanders

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The bestselling social history of Victorian domestic life, told through the letters, diaries, journals and novels of 19th-century men and women.

Some images were unavailable for this electronic edition.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

The Victorian House è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a The Victorian House di Judith Flanders in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a History e Social History. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

HistoryCategoria

Social History1

THE BEDROOM

IN THE SEGREGATION that permeated the Victorian house, the reception rooms were always considered the main rooms – they presented the public face of the family, defining it, clarifying its status. Bedrooms, to perform their function properly, were expected to separate servants from employers, adults from children, boys from girls, older children from babies. Initially, smaller houses had had only two bedrooms, one for parents and young children, one for the remaining children, with servants sleeping in the kitchen or basement. To accommodate the increasing demands for separation, houses throughout the period grew ever taller.

In addition, the older fashion of the bedrooms serving as quasi-sitting rooms was, in theory at least, disappearing. The Architect said that using a bedroom for a function other than sleeping was ‘unwholesome, immoral, and contrary to the well-understood principle that every important function of life required a separate room’.1 In actual fact, bedroom function was regulated rather less rigidly than the theory of the times advocated. Throughout the period, as well as being rooms for sleeping, for illness, for sex,* for childbirth, bedrooms served more than one category of family member. Alfred Bennett, growing up in the 1850s in Islington, slept on a small bed beside his parents’ bed.* So did Edmund Gosse, until his mother developed breast cancer when he was seven; after she died, he slept in his father’s room until he was eleven. In small houses this was to be expected. Thomas and Jane Carlyle’s procession of servants slept in the back kitchen, or scullery, from 1834 (when the Carlyles moved into their Cheyne Row house) until 1865 (when an additional bedroom was incorporated in the attic). The house was fairly small, but they had no children, and for many years only one servant. Even in large houses with numerous servants it was not uncommon to expect them to sleep where they worked. As late as 1891 Alice James reported that a friend, house-hunting, had seen ‘a largish house in Palace Gardens Terrace [in the new part of Kensington: this was not an old house] with four reception rooms and “eight masters’ bedrooms”; when she asked the “lady-housekeeper” where the servants’ rooms were, she said: “downstairs next the kitchen” – “How many?” “One” – at [her] exclamation of horror, she replied: “It is large enough for three” – maids: of course there was the pantry and scullery for the butler and footman.’2

Like the Carlyles, it is probable that these unknown employers themselves had separate bedrooms. Even couples who shared a room often found it desirable for the husband to have a separate dressing room for himself – this was genteel: that is, what the upper middle and upper classes did, even if the shifts many had to go through to carve out this extra space often reduced the genteel to the ludicrous. (See Adolphus Crosbie’s dressing room on page xlv.) Linley and Marion Sambourne, an upper-middle-class couple living in a fairly large house in Kensington, shared a bedroom, with a separate dressing room next door for Linley.* Their two children, a boy and a girl, slept in one room on the top floor, next to the parlourmaid, while the cook and the housemaid slept in the back kitchen.3 When the children grew too old for it to be considered proper for them to share a room, Linley’s dressing room became his son’s room, and their daughter remained in her childhood bedroom: this was all fairly standard.

Yet even when the occupancy was dense, Mrs Haweis, an arbiter of fashionable interior decoration in several books, was firm about segregation of function: ‘Gentlemen should be discouraged from using toilet towels to sop up ink and spilt water; for such accidents, a duster or two may hang on the towel-horse.’4 That this warning was necessary implies that ink was regularly used in a room where there was a towel rail, and from Mrs Haweis’s detailed description that could only be the bedroom. This was clearly an on-going situation. Aunt Stanbury, Trollope’s resolutely old-fashioned spinster in He Knew He Was Right twenty years later, loathed this promiscuous mixing: ‘It was one of the theories of her life that different rooms should be used only for the purposes for which they were intended. She never allowed pens and ink up into the bed-rooms, and had she ever heard that any guest in her house was reading in bed, she would have made an instant personal attack upon that guest.’5

Bedroom furniture varied widely, from elaborate bedroom and toilet suites, to cheap beds, furniture that was no longer sufficiently good to be downstairs in the formal reception rooms, and old, recut carpeting. Mrs Panton describes the bedrooms of her youth in the 1850s and 1860s with some feeling – particularly

the carpet, a threadbare monstrosity, with great sprawling green leaves and red blotches, ‘made over’ … from a first appearance in a drawing-room, where it had spent a long and honoured existence, and where its enormous design was not quite as much out of place as it was in the upper chambers. Indeed, the bedrooms, as a whole, seemed to be furnished as regards a good many items out of the cast-off raiment of the downstairs rooms.6

As the daughter of W. P. Frith, an enormously popular painter, Mrs Panton had hardly grown up in a house where the taste was either lacking or unable to be achieved through scarcity of money. Nor was her childhood home, to use one of her favourite words, ‘inartistic’: this make-do-and-mend system was the norm.

By mid-century, bedrooms were beginning to be furnished to the standards of the reception rooms, where possible. This meant a good carpet, furniture (mahogany for preference) that included a central table, a wardrobe, a toilet table, chairs, a small bookcase and a ‘cheffonier’, a small, low cupboard with a sideboard top. The bed, if possible, was still four-postered, with curtains. There was also a washstand, in birchwood (which, unlike darker woods, did not show water stains), with accoutrements, a pier glass, and perhaps a couch or chaise longue. In Arnold Bennett’s The Old Wives’ Tale, in which he reworked some of his childhood memories from the Potteries of the 1870s, the master bedroom of the town’s chief linen-draper was splendid with ‘majestic mahogany … crimson rep curtains edged with gold … [and a] white, heavily tasselled counterpane’.7

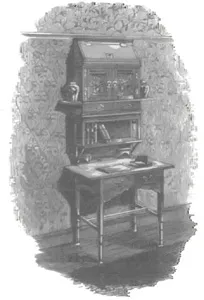

Multi-functionality: a suggestion for a bedroom writing table with, over it, a combination bookshelf and medicine case for when the bedroom was required to double as a sickroom.

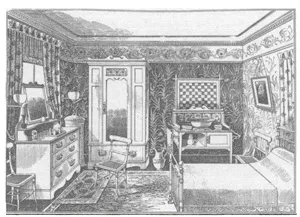

Heal’s and Son, the great furniture shop on Tottenham Court Road, suggested a bedroom furnished in Aesthetic style for the prosperous. Note that by 1896 the bed has no hangings, and gas jets illuminate the dressing mirror, although not the bed, which still has no bedside table.

The range of furniture varied with income and taste. A mahogany wardrobe cost anything from 8 to 80 guineas, while an inexpensive cupboard could be made in the recess of the chimney breast, simply using a deal board, pegs and a curtain in front. Trays and boxes for storing clothes were common – hangers were not in general use until the 1900s (when they were referred to as ‘shoulders’), so clothes either hung from pegs or were folded. Small houses and yards of fabric in every dress meant that advice books were constantly contriving additional storage: in hollow stools, benches, ottomans. Even bulkier items were folded: Robert Edis, another interiors expert, recommended that halls should have cupboards ‘with shelves arranged for coats’.8 ‘Ware’ – shorthand for toilet-ware – also came in a range of qualities. The typical washstand had towel rails on each side, and often tiles at the back to protect against splashing water. It was expected there would be a basin, a ewer or jug, a soapdish, a dish to hold a sponge, a dish to hold a toothbrush, a dish to hold a nailbrush, a water bottle and a glass. A chamber pot might be of the same pattern as the ware. Mrs Panton recommended that identical ware should be bought for most of the bedrooms, as breakages could then be replaced from stock – breakages of bedroom items, she implied, were frequent. A hip bath might also live in the bedroom, to be filled by toilet cans: large metal cans of brass or copper, which were used to carry hot water up from the kitchen.

No room was finished without its ration of ornaments: Mrs Haweis said that even without much money one could have a pretty room: ‘A little distemper in good colours, one or two really graceful chairs … a few thoroughly good ornaments, make a mere cell habitable.’9 Mrs Caddy, in her book on Household Organization, suggested that, as with the furniture and carpets, second best would do for the bedroom – ‘light ornaments … which may be too small, or too trifling, to be placed with advantage in the drawing room’.10 Certainly the desire for small decorative objects was no less upstairs than down. Marion Sambourne’s dressing table in the 1880s had on it five jewel boxes, a brush-and-comb set, a card case, two sachets, six needlework doilies, three ring trays, a pin cushion and a velvet ‘mouchoir case’.11

Bedside tables as we know them were not current. In sickroom literature, nurses were always being advised to bring a table to the bedside to hold the medicines. Mrs Panton, with her love of soft furnishings, suggested for the healthy ‘a bed pocket made out of a Japanese fan, covered with soft silk, and the pocket itself made out of plush, and nailed within easy reach’, to hold a watch, a handkerchief etc., and then, as an innovation which required explanation, ‘furthermore … great comfort is to be had from a table at one’s bedside, on which one can stand one’s book or anything one may be likely to want in the night’.12

Mrs Panton’s bed was a brass half-tester, which had fabric curtains only at the head, lined to match the furniture. This was in keeping with the style of the later part of the century. As more became known about disease transmission, home decorators were urged to keep bedroom furnishings to a minimum, although this frequently given advice must be compared to actuality. A list of objects in Marion Sambourne’s room included a wardrobe, a cupboard to hold a chamber pot, a towel rail, a sofa, a box covered in fabric, two tables, a bookcase, a linen basket, a portmanteau, a vase, two jardinières, plus ten chairs and the dressing table with its display.13 For not all agreed that bed-hangings were unhealthy: Cassell’s Household Guide as late as 1869 thought that draughts were more of a worry than the hangings that kept them away from the sleeper.14 In general, however, four-posters were vanishing. Even if people were not switching to simple iron or brass beds, as advised, they were at least replacing the traditional heavy drapery with beds with only vestigial curtains. The simplified lines of such beds were disturbing to some: Mrs Panton advised that ‘If the bare appearance of an uncurtained bed is objected to’, one could mimic the more familiar style by putting the startlingly naked bed in a curtained alcove.15 Likewise, while carpets did not disappear entirely, they were modified so that they could be taken up and beaten regularly, or rugs were substituted, so that the floor could be scrubbed every week.

As the second half of the century progressed, hygiene became the overriding concern. Mrs Panton, still distressed about bedroom carpets, remembered a carpet that had spent twenty years on the dining-room floor, ‘covered in holland in the summer,* and preserved from winter wear by the most appallingly frightful printed red and green “felt square” I ever saw’. When it was no longer considered to be in good condition, it was moved to the schoolroom, then demoted once more, to the girls’ bedroom. (Note that the schoolroom, a ‘public’ room for children, got the carpet before the children’s bedroom did.) After that, it was cut into strips and put by the servants’ beds, ‘and when I consider the dirt and dust that has become part and parcel of it, I am only thankful that our pretty cheap carpets do not last as carpets used to do, for I am sure such a possession cannot be healthy’.16

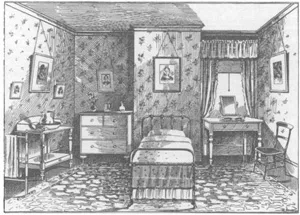

As suggested by Heal’s ...