![]()

Part I

The Great Irish Famine [An Gorta Mór], 1845 to 1850

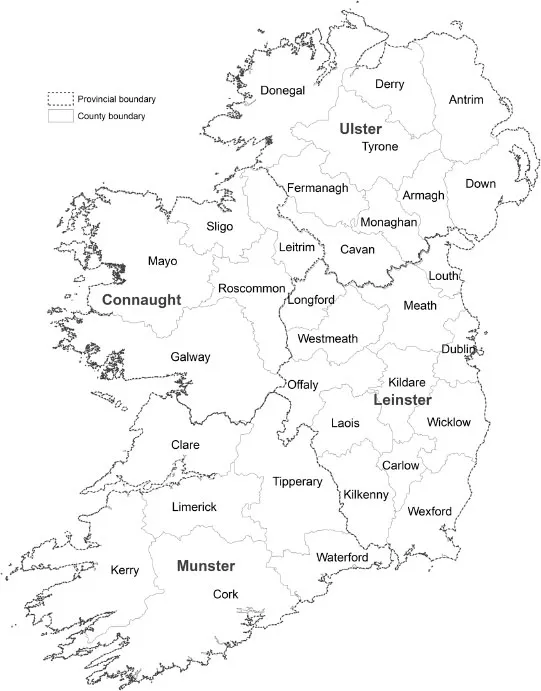

Map PI.1 Provinces and counties of Ireland.

![]()

1 From the ‘haggart’ to the Hudson

The Irish famine across many geographical scales

Declan Curran

Introduction

Where does the local end and the regional, national or international begin? When the impact of a natural disaster, such as an epidemic or famine, or a man-made calamity, such as armed conflict or an economic crisis, is characterised as being, say, localised or regional, does this adequately capture the manner in which this event unfolds across places and over time? Similarly, does the notion of a national or international emergency convey the variation in how such a widespread development might be experienced ‘on the ground’? While what follows is ostensibly an overview of socio-economic aspects of the Great Irish Famine, this chapter highlights the fact that the impacts of such a disaster are felt across many geographic scales simultaneously and that pre-existing local and regional differences, both spatial and social, influence how the ensuing distress is experienced by individuals and households.1 This chapter discusses pre- and post-famine Ireland in an international context, while at the same time acknowledging the local and regional distinctions within Ireland that had become firmly established in the years prior to the famine.2

Ireland before the famine

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, Ireland experienced a period of rapid social and economic change. In an international context, a series of technological improvements in textiles and a major geopolitical event, the Napoleonic Wars of 1793 to 1815, provided a great stimulus to Irish economic development and, through their interaction with existing social and economic structures within Ireland, these developments had far-reaching consequences for Irish living standards. The Napoleonic Wars, in particular, brought about a wartime boom in farm prices, which benefited not only large dairy farmers but also smallholders involved in tillage and pig production. At the same time, textiles had emerged as an important cottage industry, supplementing rural farm incomes. These economic developments were accompanied by an unprecedented population explosion, particularly in Connaught and Munster whose greater proportion of small farmers reaped the benefits of the wartime boom.3 However, the end of the war in 1815, along with the collapse of the domestic textile industry, ushered in an era of economic turbulence between 1815 and the eve of the famine.

Pre-famine economic development

As the 1700s progressed, increased British industrialisation led to a strengthening in demand for Irish agricultural exports and ushered in an era of prolonged agriculture price increases. Crotty points to the repeal of the Cattle Acts in 1760 as the embodiment of Britain’s changing economic orientation from finding markets for its own agricultural output to finding food supplies for its manufacturers and commercial consumers.4 The Cattle Acts, enacted in the 1680s, placed an embargo on the British importation of livestock from Ireland. In Crotty’s view, these acts had inadvertently served as the catalyst for Ireland’s one great industry of the eighteenth century: the provisions trade. Trade in salted meats emerged in place of the export of livestock, and these foodstuffs were exported to Britain, its colonies, and mainland Europe. Subsidiary trades such as cooperage, tanning and tallow manufacturing also emerged, and the resultant increase in employment and income created a strong domestic demand for dairy produce and corn.

Irish agriculture was further boosted by Britain’s involvement in the Napoleonic wars (1793–1815). These wars were characterised by economic warfare between Britain and France, as each tried to restrict the other country’s trade.5 The outlook for Irish agriculture remained positive as long as Britain continued to wage war. War necessitated the suspension of the Gold Standard (the convertibility of paper currency notes into a fixed quantity of gold) and ushered in a period of price inflation, it conferred near-monopoly status on Ireland as supplier of British foodstuff due to the blockade of continental food supplies, and it presented Irish Agriculture with the lucrative requirements of the British army and navy for provisions.6 However, Cullen notes that Irish prosperity during this period may have owed more to price increases than to increased volumes of exports: Irish exports rose by 120 per cent in monetary terms over the duration of the Napoleonic wars, while the volume of exports rose by only 40 per cent over this period.7

It was grain exports, in particular, that benefited from the surge in British wartime demand and this gave impetus to a restructuring of Irish agricultural production from pasture to tillage.8 Tillage gave a higher gross output per acre than either dairy farming or grazing.9 Legislation providing government bounties to grain exporters in 1758 and 1784 reinforced this trend.10 The emergence of the potato in Irish society in the 1750s, with its appeal both as a high-yield root crop and as a nutrition-rich subsistence food for labourers, also contributed to both economic growth and rapid population growth. According to Crotty, the labour-intensive nature of tillage encouraged the subdivision of landholdings in order to provide additional labourers with a means of subsistence through potato cultivation.11 Cullen, on the other hand, contends that the expansion of the potato crop was a response to, rather than a cause of, Irish population growth: the growing population reduced the price of labour and thus made a shift into more labour-intensive arable crops more attractive.12 As Mokyr notes, arable production as a whole benefited from a technological improvement in the shape of accelerating diffusion of potatoes after 1750.13 Taken together, the wartime boom and the potato’s emergence as the ultimate subsistence crop brought about a vast agricultural expansion in the form of increased tillage acreage.

The end of the war in 1815 brought with it severe difficulties for Irish agriculture, particularly for tillage farming.14 The reopening of the British market to grain imports from continental Europe, demobilisation of the British army and navy, and the falling prices associated with the return to the gold standard all combined to create a more challenging environment for Irish agriculture. A banking crisis in 1820, due to Bank of Ireland’s efforts to restrict credit in the face of Britain’s deflationary return to the gold standard, and again in 1826, as a currency union between Ireland and Britain was being implemented as part of the 1800 Act of Union, prolonged the difficulties of the agricultural industry.15 Irish agriculture did overcome this post-war slump, as prices of grain, livestock and livestock products began to recover in the 1830s, and export volumes of livestock, grain and butter expanded once again.16 However, the domestic textiles industry, which had been the second major area of economic expansion in eighteenth-century Ireland, entered into a terminal decline during this period.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, exports of non-agricultural goods, particularly linen, cotton and woollen goods, increased significantly relative to agricultural exports. By the 1790s, the Irish Customs Ledger indicated that textiles accounted for 60 per cent of the value of total Irish exports, almost double the value of all Irish agricultural exports combined.17 O’Malley attributes the burgeoning Irish textile industry at this time to the labour-intensive nature of the work and relatively low Irish wages, while he traces the origins of the Ulster’s strength in this industry to the seventeenth-century influx of Hugoenot and British immigrants skilled in textile manufacturing.18 Linen was the most successful of the Irish textile industries and by 1800 linen had developed into a major rural cottage industry, emerging in northeast Ulster and spreading across the northern half of the country and into isolated parts of the west.19 The principal export markets for Irish linen were Britain and North America.20 The textile industry provided an additional source of employment and income, with many families working in both agriculture and domestic textile production. Many landless labourers and smaller tenant farmers earned additional income, either by spinning yarn or weaving coarser fabrics, while many weavers rented a plot of land where they grew potatoes but paid the rent from weaving earnings.21

In the early 1800s, the linen industry was adapting to mechanised technology at a slower pace than the cotton industry. Belfast experienced a move away from linen to cotton, and cotton spinning mills began to concentrate in the Belfast area. Outlying districts of Ulster and beyond remained active in the linen industry, particularly in fine linen where they had established a strong competitive position.22 Eventually, technological advances were incorporated into Irish linen production. Wet spinning, devised in France in 1810, was introduced in Britain and Ireland in the 1820s.23 Now powered spinning of fine linen was possible and, in the face of competitive pressures, many Belfast cotton mills changed over to linen production. Belfast’s large population of skilled weavers and existing mills put it in a strong position to capitalise on the new linen technology and establish itself as an early centre of mechanised fine linen spinning.24 However, the domestic textile industry that had provided supplementary income to the rural poor could not compete in the face of large-scale mechanised production. Landless labourers, cottiers and smaller tenant farmers were now almost exclusively dependent on farming, and in particular the potato crop, for subsistence.

While there appears to be a consensus that Ireland experienced a process of deindustrialisation in the first half of the nineteenth century, a divergence of views has emerged with respect to the extent and cause of this deindustrialisation.25 Regarding the extent of deindustrialisation, Cullen argues that deindustrialisation was confined to the textile industry, and that other domestic industries such as milling, brewing, iron founding, shipbuilding, rope making, paper and glass making benefited from large-scale production and centralisation.26 Both Mokyr and Solar, on the other hand, speak of a wider deindustrialisation process.27 As for the causes of deindustrialisation, the traditional nationalist view, as articulated by O’Brien, held that the removal of protective tariffs brought about by the Act of Union left Irish industry exposed to free trade with Britain’s larger, more advanced industries.28 Ó Gráda, however, questions whether or not the 10 per cent tariffs (Union dues) removed in the 1820s as a consequence of the Act of Union would have been sufficient to protect Irish industry from competitive pressures exerted by British industry, given the dramatic decline in the prices of British industrial output.29 Mokyr attributes Irish deindustrialisation to weak trading performance in the face of competition arising from proximity to newly industrialised Britain.30 Lee points to the transport improvements that exposed Irish rural industries to competition from British large-scale producers, and attributes the absence of Irish large-scale producers to the lack of Irish entrepreneurship, as well as a dearth of natural resources.31 However, O’Malley argues that deindustrialisation may not have been primarily due to internal i...