eBook - ePub

International Business Geography

Piet Pellenbarg, Egbert Wever

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 304 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

International Business Geography

Piet Pellenbarg, Egbert Wever

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Written by eminent scholars who are well known within their fields across Europe, this book explores changes in the international economic environment, their impacts on the strategy of firms and the spatial consequences of these changes in strategy.The economic environment in which major companies operate is subject to rapid and important changes.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

International Business Geography è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a International Business Geography di Piet Pellenbarg, Egbert Wever in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Betriebswirtschaft e Business allgemein. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 The corporate firm in a spatial context

Piet Pellenbarg and Egbert Wever

Introduction

Firms continually face changes in their business environment. Their reactions to these changes can have far-reaching consequences for the geographical organization of their activities, and therefore also for the regions in which their activities are located and for their workers. Ample examples of these dynamics can be found in daily newspapers. A random sample from recent Dutch newspapers, for example, offers a dazzling variety of news items about the international movements of corporate activities.

- An increasing number of Dutch multinational firms are nowadays aware of the attractive conditions for carrying out specific activities in India. (The headline says “Workers in India work hard and we in the Netherlands will notice that!”) In the beginning of 2005 already 36,000 East Indians were employed by food producer Unilever. The ABN AMRO Bank hired more than 4,000 East Indian workers and Philips more than 3,000. These figures suggest that jobs are disappearing from the Netherlands – at least that is the consent among the Dutch. Other news items seem to confirm this idea: for example, fine chemicals producer DSM closed a penicillin plant in the Netherlands and opened new ones in India and China.

- When, on the first of January 2005, the last EU trade restrictions for clothing and textiles were abolished, a newspaper reported on this issue under the headline “Landslide in textiles”. The article discussed the intention of France and Italy, the biggest European producers, to sign a strategic arrangement in order to protect the European textile industry against imports from China.

- Since the crumbling of the Iron Curtain, an increasing part of the spatial rearrangement of Western European multinational firms’ activities is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe. A newspaper article announced that “Poland is becoming the bookkeeper for Europe”, emphasizing Poland as an increasingly tough competitor for a country like India. The article also mentioned that Philips and Lufthansa have already established administrative centers, respectively in Lodz and Krakow.

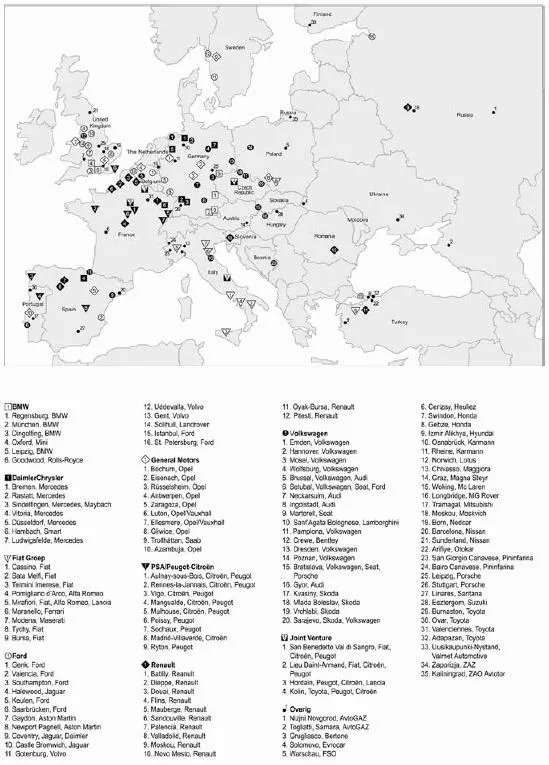

- A report titled “The car industry is moving to East Europe”, lists a number of plants now located in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bosnia and Slovenia. Figure 1.1 depicts this flight of the car industry to Eastern Europe in more detail.

- The flight of jobs concerns all sectors, not only manufacturing; and all continents, not only South and Southeast Asia. Newspapers reported, for example, that AHOLD, the biggest Dutch retail company (worldwide ranked fourth after Walmart, Carrefour and Metro), has a customer service call centre in Cape Town, South Africa.

- International movements are not exclusively motivated by the pursuit of cost efficiency. One newspaper reported, for example, about Inalfa, a Dutch company of sliding roofs and metal components for cars. This company opened a new assembly line in Grand Blanc in the state of Michigan, USA, a line that will work with and for companies such as Chrysler and Dodge.

- The business landscape changes as a result of the reallocation of activities, but even more in terms of ownership, as many newspaper articles show. We can easily grab half a dozen examples: the French TV producer Thomson stepped into a joint venture with TCL, the biggest Chinese producer of TVs and mobile telephones. A few years earlier, TCL had already bought the German TV producer Schneider. Lenovo from China took over the pc activities of IBM. The Russian firm, Amtel, took over the Dutch producer of expensive car tires, Vredestein. The co-operative dairy companies: Arla (from Denmark) and Campina (from the Netherlands), considered a merger that would make them the biggest in the world after Nestlé. The merger did not materialize. Mittal Steel from India, now the biggest steel company in the world, succeeded in taking over Arcelor, number two in the global steel sector, and announced their wish to move their international head office from Rotterdam to Luxemburg. The states of Kuwait and the emirate Dubai belong to the major shareholders of the German–American company DaimlerChrysler.

All of the companies in these examples deal with international competition and changing ‘firm external’ conditions, but some sub-categories can be identified. One of them deals with specific conditions of locations, such as low costs. The car factories in Eastern Europe and the expected changes in the shoe and textile landscapes are examples of the influence of such ‘firm external’ factors. Firms can also improve their competitive position by penetrating into new markets. Inalfa entering the US market, is a clear example, but at least part of the presence of Dutch banks in India, and the new production facilities of DSM and Philips in India and China can also be explained by the opportunities offered by the emerging markets over there. This argument also holds for the Chinese, Indian, and Middle Eastern firms taking over or buying shares in ‘western’ companies. They buy market positions, sometimes including strong brand names. A third category in the newspaper reports has a link with ‘firm internal’ arguments. The considered merger of Arla and Campina is an example, as is the takeover of Vredestein by Amtel. In these cases, firms anticipate that collaboration, using complementary competences (technology, finance, and marketing) and reducing costs because of scale economies, will enable them to cope better with growing international competition. But there too, the interplay between internal and external changes is relevant. Changes in the ‘firm external’ environment may lead to changes in the internal structure of firms, as exemplified by the case studies in the first edition of this book (de Smidt and Wever 1990) and proven again by some of the cases in this volume.

Figure 1.1 The flight of car manufacturing to Eastern Europe (source: NRC/Automotive News Europe 2005).

How can we more fully understand the complex changes in the global patterns of production as exemplified by the newspaper reports and the cases treated in this book? The obvious thing to do is to watch what happens on the level of the individual firm. Firms can be seen as the “containers of production” (Walker 2003, p. 119). When spatial production patterns change we may expect to find the explanations within the decision-making units of these ‘containers’. But that raises the question: what exactly is a ‘firm’? Firms appear in many shapes: small and big, single plant and multi-plant, private and public (state-owned). In this book, we concentrate mostly on corporate firms, more particularly multinational corporations, as they are at the core of the internationally oriented ‘enterprise approach’ since that approach was formulated half a century ago by economic geographer McNee (1958, 1960). Because our case studies are so evidently focused on the three related categories of ‘firm’, ‘place’ and ‘replacement of activities’ economic geography seems the most natural discipline to derive conceptual bases and relevant theories.

The theory of the firm

Reviewing “the concept of the firm in economic geography”, Taylor and Asheim (2001, p. 315) argue that economic geographers have left ‘the category of firms . . . ambiguous because it has rarely been defined with precision’. According to these authors the lack of precision seems to emanate from a lack of real interest in the nature of the firm itself. Quoting Nooteboom (1999), Taylor (1984) and Dicken and Thrift (1992), they point out that economic geographers usually conceptualize the firm as “a phenotype instead of a genotype”: “just a site where social and economic processes meet and interact”, “a game board rather than a player in the game”. However, depending on the paradigm that was chosen as the point of departure, there are a number of different looking ‘game boards’. Taylor and Asheim (2001, p. 316) identify no less than nine, yet overlapping, conceptualizations of the firm.

The neoclassical view treats firms as ‘black boxes’ that change place as a rational way of responding to changes in factor prices

In neoclassical theory, rooted in the work of Adam Smith, a firm is an entity run by a well-informed management that essentially makes rational choices on the allocation of resources. A firm is completely characterized by its production function, in fact it “is a phantom, a production function endowed with perfect knowledge and set to maximize” (Taylor and Asheim 2001, p. 317). Minimizing costs and maximizing sales and profits are marked elements of any firm’s behavior, including its spatial choice behavior. Among well-known authors of theories on location choice working from a neoclassical basis are Von Thünen (1826), Weber (1909), Christaller (1933), Lösch (1944), Hoover (1948) and Smith (1971). The general principles of neoclassical theory were outlined by Isard (1956). Although considered out of date by most economic geographers, neoclassical principles are still frequently used, especially in quantitative models of industrial location used in spatial economics.

The behavioral view accepts rationality as a background for less optimal reactions on changes in the firm’s environment

The new principles of bounded rationality and sub-optimal ‘satisfying’ behavior (as an opposite of maximizing behavior) were developed by Nobel prize winner Herbert Simon in the 1950s (Simon 1960). The most well-known translation of these new concepts to location choice behavior is Pred’s ‘behavioral matrix’ in which the level of information and the ability to use information have replaced the classical primary location factors of transportation costs, labor costs and agglomeration advantages (Pred 1967). The acceptance of location choices, often based on incomplete information and less rational arguing, led to interesting studies on the ‘mental map’ of entrepreneurs (i.e. Meester and Pellenbarg 2006), but a major new location theory based on behavioral principles never developed.

The structuralist view sees the firm as less important as the pressures of class and capital

The structuralist theory draws on the Marxist view that capitalism tends to exploit labor and creates class divisions. In this paradigm, the industrial location pattern is understood as the result of the clash of labor and capital, a clash in which businesses and governments are in fact just passive players (Massey 1979). The location choice or change is only interesting in terms of the effects it has on employment, income and the structures of power rather than in and of itself. Like the neoclassical and behavioral approaches, the structuralist approach is now outside the main flow of economic geographic thinking (especially after the communist economies in Eastern Europe collapsed), but still has its defenders (Swyngedouw 2003).

The institutionalist view defines the firm as a site of rules and routines rather than as a place of work

The institutionalist approach tries to understand the activities of firms within wider social, economic and political structures. This approach focuses on the role that is played by systems of rules, procedures and conventions, both formal (laws, regulations) and informal (standards, values, and conventions). Institutions aim to reduce transaction costs and in doing so, help develop successful local and regional economies; this is considered to be more important than the transport conditions and localized production factors that figure more prominently in the neoclassical approach. Veblen (1899) is often mentioned as the founding father of the institutionalist approach, but fundamental additions were made by Polyani (1944) and later Granovetter (1985). The latter developed a sociological view on institutionalism, as well as the concept of ‘embeddedness’ as an indicator of the degree in which firms are rooted in social, economic and political structures.

The network perspective sees the firm as an organization embedded in socially constructed networks of reciprocity and interdependence

The use of the term ‘embedded’, which highlights the way in which firms are “enmeshed in loosely coupled networks of reciprocity, interdependence and unequal power relations” (Taylor and Asheim 2001, p. 320), already suggests that the network approach is primarily an elaboration of the institutional approach. Following the institutional view, there is a particular interest in the embeddedness of economic networks into social networks. Within economic geography, the network view had a substantial influence on research and publications in the past two decades in the area of new and popular concepts such as ‘new industrial spaces’, ‘industrial districts’, regional innovation systems’, and ‘innovative milieus’ (Scott 1988; Asheim 1994; Braczyk et al. 1998).

The learning firm concept views the firm as a gathering of learning capabilities, embodied in its workers

The concept of the firm as a learning organization has many fathers (see Taylor and Asheim 2001) but according to Atzema et al. (2002) it is rooted, at least in part, in the ideas of the Danish economist Lundvall (1992). Following Schumpeter, Lundvall regards innovation as a process, but not merely a process experienced by the entrepreneur as a person, but as a collective learning process involving larger groups of individuals within the organization. Innovation, in his view, is not so much the expected outcome of investment in research and development (henceforth referred to as R&D) departments of big firms, but the result of ‘learning-by-doing’, ‘learning-by-using’ and ‘learning-by-interacting’. Authors like Florida (1995) and Morgan (1997) transferred the same idea to regions (c...