![]()

1

The Chinese Connection

One of the world’s major opium-cultivation and heroin-producing areas is the Golden Triangle, a 150,000-square-mile, mountainous area located where the borders of Burma (or Myanmar),1 Laos, and Thailand meet.2 Although there is a geographical region promoted by the tourism industry as the Golden Triangle where the Mekong River flows through the three countries, when it comes to drug production and trafficking activities, the territory refers to a much larger area, including most border regions between Thailand and Burma and between China and Burma.3

For decades and up until the late 1990s, the Golden Triangle had a notorious reputation as the “breadbasket” of the world’s heroin trade.4 By the end of the decade, Burma was producing more than 50 percent of the world’s raw opium and refining as much as 75 percent of the world’s heroin.5 Recently, Burma has also become a main source of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) in Asia, producing hundreds of millions of methamphetamine tablets annually.6

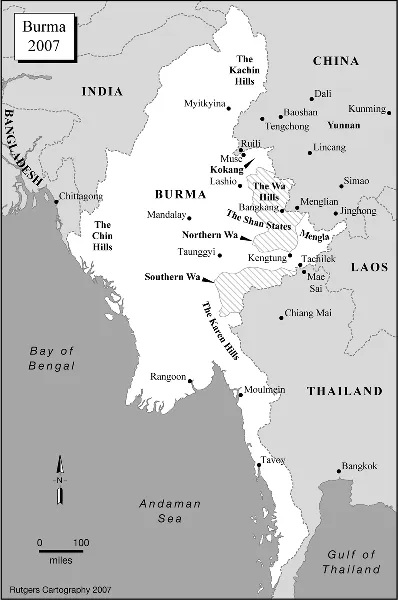

The Golden Triangle has long fascinated researchers and anti-narcotics agencies around the world, and much of the fascination centers on Burma because of its colonial past with the West and its political isolation. Burma’s major opium-growing and heroin-producing area is located in the Shan State, which is occupied by various ethnic armed groups and was the base of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) before it collapsed in 1989.7 According to Burmese authorities, the CPB was bankrolled by China as well as supported by various non-Burmese ethnic groups and was considered the major threat to their regime.8 After the disintegration of the CPB, the Burmese regime arranged cease-fire agreements with various former CPB groups in the Shan State.9 The ethnic groups promised not to fight against the Burmese government and, in return, the Burmese authorities allowed these ethnic groups to keep their armed forces and to continue their opium trade.10 The areas associated with the three armed groups believed to be most actively involved in the drug trade are the Kokang Area or the No. 1 Special Zone, the Wa Area or the No. 2 Special Zone, and the Mengla Area or the No. 4 Special Zone (see map 1.1).11 Consequently, U.S. sources estimated that Burma’s opium production virtually doubled from 1,250 metric tons in 1988 to 2,450 metric tons the following year and continued to increase thereafter, to 2,600 metric tons in 1997.12 As the relationship improved between the Burmese authorities and the ethnic groups in the Shan State, more and more money from the drug trade poured into legitimate businesses and fueled the expansion of the Burmese economy.13

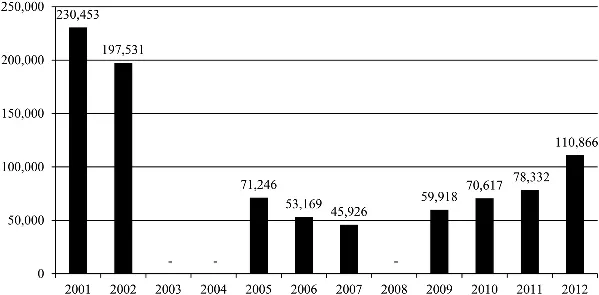

Although international anti-narcotic efforts have affected the scale of raw opium production, the scale of opium poppy cultivation is still considerable. Since most opium poppy cultivation is located in northern Burma, bordering China’s Yunnan Province, the Chinese authorities for years have attempted to intervene and reduce the production of raw opium and heroin because much of the drug has been exported either through China or directly for China’s consumption. Since the late 1990s, Chinese authorities have been tracking and estimating the size of opium cultivation acreage via informants on the ground and satellite imaging. The estimates are reported, although not consistently, in the Annual Report on Drug Control in China. According to the reports, the total opium cultivation was on an overall decline to a low of 279,000 mu (or 18,600 hectares) in three decades.14 In the past few years, however, the total opium poppy cultivation in northern Burma started an upward trend and the magnitude of increase alarmed the Chinese authorities. Figure 1.1 depicts the data assembled from the annual reports issued between 2001 and 2012.

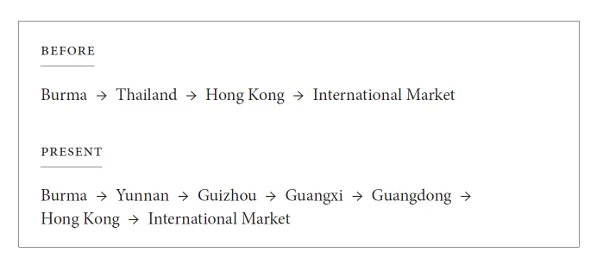

Before the mid-1980s, heroin produced in the Golden Triangle was mostly smuggled into Thailand over land and then to Hong Kong on Thai fishing trawlers before being transported to the United States, Europe, and Australia.15 Hong Kong was, and probably still is, the organizational and financial center for the region’s heroin trade.16 However, in the late 1970s, rapid expansion in commerce and population migration inside China led to the opening up of cross-border drug trade between Burma and China.17 On April 12, 1986, 22 kilograms of heroin were seized by the authorities in Yunnan Province, in the southwest corner of China that borders Burma, Laos, and Vietnam. The drug case, masterminded by drug traffickers from Thailand and Hong Kong, was considered the first major case of its kind since China came under communist control in 1949.18 The authorities at the time simply had not encountered any such heavy loads. In May 1994, the police in Yunnan caught another notorious drug lord named Yang Maoxian (the brother of Yang Maoliang, who was then the leader of the Kokang area) and sentenced him to death.19 A year later, Lee Guoting, another Kokang leader and a well-known heroin kingpin, was arrested and executed by the Chinese authorities. It was clear by then that the Chinese route had become popular for transnational drug traffickers.

The booming drug trafficking business in China can be attributed to two main factors. First, a sizeable domestic drug consumption market has emerged. By the mid-1980s, drug addiction was no longer confined to the border areas. The Chinese government now openly acknowledges that every province and all major urban areas have drug problems. China is no longer just a transit country favored by transnational criminal organizations; it, too, has a sizeable addict population of its own.20 According to official statistics, there were 148,000 officially registered drug addicts in China in 1991. A decade later, the number had jumped to more than 900,000. The latest official count of drug addicts in China exceeded 1.5 million.21 Heroin remains the predominant drug of choice for addicts; however, users of synthetic drugs are also increasing rapidly, particularly among urban youths.

Second, drug traffickers developed alternative routes through China (mostly along China’s southern provinces—Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Guangdong) in response to changes in the regional drug trade (see figure 1.2 and map 1.2). In 1989, after the Burmese authorities signed peace agreements with the various armed groups located in northeastern Burma, they turned their attention to Khun Sa, also known as the King of Heroin, who had long dominated the heroin business along the Thai-Burma border. After the Burmese assaults intensified, and as more and more Wa soldiers joined forces in the campaign against Khun Sa, the drug lord abruptly surrendered to the Burmese authorities in 1996.22 With the collapse of Khun Sa’s Mong Tai Army (MTA), the southern, or Thai, trafficking route was disrupted. As a result, the China route became all the more important for drug traffickers in Burma, especially when, in the late 1990s, their investments and savings in Thailand and Burma were diminished by the depreciation of the Thai baht and Burmese kyat. Drug traffickers came to realize that the Chinese yuan was more desirable than either the Thai baht or Burmese kyat.23

Moreover, for drug traffickers in the Golden Triangle who are predominantly ethnic Chinese, the China route is far better than the Thai route because of geographical proximity, better road conditions, and cultural and linguistic familiarities. However, armed group leaders in the region have traditionally been reluctant to take full advantage of this route, fearing that if China shuts down its border, the area will be completely isolated. Ironically, when a major confrontation erupted in 2001 between the Burmese and Thai border forces, and the Burmese authorities shut down all the border crossings in retaliation, the Thai-Burma border trade all but came to a complete halt. This incident prompted drug traffickers to earnestly cultivate a passage through China.24 Despite China’s efforts to combat drug imports along its southwestern borders, Burma remains its largest source of illicit drugs. After analyzing all the drug cases between 2006 and 2007 for six jurisdictions in southern China, Huang Kaicheng and his colleagues at China’s Southwest University of Political Science and Law found that “more than two thirds (68.9%) of the cases with drugs destined for the mainland were coming from Myanmar.”25 Seizures of heroin and synthetic drugs from Yunnan Province alone account for more than half of the national total.26

Even though tens of thousands of kilograms of heroin are being smuggled every year from Burma into China, a country with probably the world’s largest heroin consumption market, there is little systematic research on the heroin trade in China. We do not know much about the people behind the transnational smuggling of heroin, the social organization of the traffickers between Burma and China, and the characteristics of heroin trade compared to those in other parts of the world. In this study, we attempt to answer some of these questions based on an empirical research project we have conducted in Burma and China. In fact, as suggested by British criminologists Geoffrey Pearson and Dick Hobbs, high-level drug trafficking is not a well-developed research field, even in drug markets in other parts of the world such as the United States and Europe.27 Thus, it is imperative to examine the social organization of a major drug market that is located in China, a country with the world’s largest population and the second largest economy.

Theoretical Guidance

A more detailed description of our conceptual framework of the social organization of the drug trade in China is presented in chapter 5. Our main theoretical interest in this project was geared mostly toward understanding how individuals find one another in their social networks to gain entry into the drug trade, manage law enforcement risks and logistical obstacles inherent in the business, and collectively and individually move toward the common goal of making money. To consider drug trafficking as an organized crime, there must be structural arrangements and patterns that transcend individual behaviors. Throughout our data collection and field activities, we were keen on examining the market conditions or transactional requisites that appeared to restrict and mitigate how individual risk takers enter the illicit marketplace, interact with one another or delegate tasks, and develop strategies and patterns of behavior to manage risks.

Broadly speaking, there are two main theoretical approaches in understanding any criminal organizations28—the corporate model and the enterprise model, which for the past two decades has been used to explain the many variations of criminal groups engaged in illicit econo...