![]()

1

A COLONIAL DYAD IN BALINESE PERFORMANCE

As I said this morning to Charlie

There is far too much music in Bali

And although as a place it’s entrancing,

There is also a thought too much dancing.

It appears that each Balinese native,

From the womb to the tomb is creative,

And although the results are quite clever,

There is too much artistic endeavour.

—Noel Coward to Charlie Chaplin

By the 1930s, when Noel Coward turned to Charlie Chaplin with this ditty about the surfeit of “artistic endeavour” in Bali,1 reports had been filtering out to Europe and America that the island, “not Fiji or Samoa or Hawaii, was the genuine, unspoiled tropical paradise, known as yet, even by reputation, only by the cognoscenti, a category with which all of the more affluent world travelers sought to identify themselves, as did a certain few more or less learned scholars.”2 Coward’s wry ascription of magic to the Balinese native, at once a kind of Asian encounter and a colonial spell, is also a queer repartee between two men undoubtedly among the cognoscenti on vacation in Bali. While one can only guess whether the generic or gender-ambiguous “Balinese native” so central to the island’s magic is a brown woman, brown boy, or both, it is clear that a colonial dyad is involved in the making of the native’s creative queerness from “the womb to the tomb.”

The poem’s opening couplet, with lines ending in “Charlie” and “Bali,” sets up the dyad as an informal relationship and suspends it across the remaining rhyming couplets, “entrancing/dancing,” “native/creative,” “clever/endeavour,” for a seductive and incantatory effect. Like a spell that is contingent upon the arrangement of words, the tightly woven metrical verse brings out the magic of Coward’s performatives while indexing Charlie’s amused if not entranced posture in Bali. Tellingly, Coward hints at the native choreography as a design that is in fact unnatural, parodying the prevalent discourse about how “everyone in Bali is an artist” with the bio-claim that the Balinese “womb” incubates creativity.3 One can thus interpret his ironic quibble about the surfeit of creative production—“far too much music” and “a thought too much dancing”—as a queer moratorium on colonial artistic production even if “the results are quite clever.” In other words, Coward’s version of the queer dyad is set apart from, even as it is imbricated in, the colonial invention of the Balinese native and the island paradise of Bali.

Bali’s makeover from “feudal” and “vestigial Dark Age”4 to “unspoiled tropical paradise” is a remarkable testament to Dutch colonial “ethical,” “protectionist,” and “conservationist” policies implemented in the 1910s.5 These policies sought to preserve selected traditions, customs, and performing art forms that the Dutch deemed essential to native Balinese culture while also appealing to tourists. Within two decades of Bali’s annexation by the Dutch in 1908, Bali’s nativized performing arts became a magical trope for the island’s idyllic character and gained a seemingly indissoluble cultural currency thereafter.

One of the nativized rituals that became iconic of the island’s cultural traditions is kecak, the Balinese performance at the heart of this chapter.6 Widely known to tourists as the “monkey dance,” kecak features a large Balinese male chorus performing a polyrhythmic chant with synchronized gestures and throbbing bodies in a multilayered circular structure. Much of its appeal centers on the transmogrification of the men into entranced monkeys from the Ramayana epic. Kecak and its possessive embodiments is a key analytic of the tropic spell cast by or cast upon the queer dyad. It enables a reading of the ritual’s choreography as the interplay of colonial, indigenous, and queer crossings. Such crossings of the dyad inflect colonial power with a queer cognate fraught with paradoxes, and have several implications for studies of race and sexuality as they pertain to performance in the Asias. The spell is thus a different kind of magic than the one generated by the colonial mandate or its cognate anthropological gaze, which together resulted in the rabid exoticization of the island’s cultural traditions.

Even as kecak is performed as a secular dance, spectators are charmed by the tantalizing assumption that it is a trance ritual that serves as a magical portal to the island’s religious and cultural essence, a “primitive” Balinese experience, as it were. Tapping into such a popular imaginary, kecak is often used to reify Bali’s spiritualized exoticism as tourist spectacle. Pictures of kecak are iconic of this tropical paradise and can be found in myriad books, postcards, and films on Bali. In kecak’s most vivid image, the density of “possessed” Balinese male bodies huddled closely together bare chest to bare chest invokes a queer memory from the 1930s, when its choreography was formalized as part of an island-wide paradisal transformation that started more than two decades prior to its invention.

Following tourist brochures produced as early as 1914 that hailed the island as the “Garden of Eden” and an “enchanted isle,” Bali appears seamlessly interpellated as the exemplar of “paradise” throughout the twentieth century and in contemporary discourse,7 from travel literature (The Last Paradise, 1930),8 musical theater and film (“Bali Hai” in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, 1940s and 1950s),9 and scholarly publications (Bali: A Paradise Created, 1989; and The Dark Side of Paradise: Political Violence in Bali, 1995),10 to newspaper headlines (“Paradise Lost,” 2002, 2012).11 These paradisal representations tell the story of colonial fantasy, possessive vision, and transnational love. It is a love story that is mostly understood through the figure of the brown woman since the gender of Bali, as produced by the dominant discourse, is female; and “Bali as a woman” is subject to the Western male gaze or patronage and penetration. The iconic female Legong dancer, for instance, is representative of this gendered imaginary or romance. Meanwhile, the queer erotics of the colonial encounter, particularly the figure of the brown boy imbricated in Bali’s cultural transformation as paradise, are obfuscated in the mix of hetero-fantasy, possession, and love.

But among the glittering circle of visitors attracted to this “tropical Shangri-la” in the 1920–1930s is a queer cast not known for their fidelity to orthodox practice, including Coward and Chaplin as well as Colin McPhee, Margaret Mead, and many others. They form an influential group of stars and scholars, writers and artists whose time in Bali created a cultural legacy that reverberates across the world of performance from Broadway musical to Hollywood film as well as ethnomusicology, anthropology, modern art, and photography. At the center of this “charmed circle” is the German expatriate artist Walter Spies, whose café salon is the epicenter of their Balinese encounters.

As the charismatic host, Spies led his visitors to what he deemed the most authentic parts of Balinese life, such as cockfights and trance rituals. Those spellbinding encounters then became the basis of their creative or scholarly—and often very personal—output. Their letters, photographs, films, and ethnographies helped to concretize the grand colonial narrative of the island as a beautiful but politically bankrupt dreamland sustained by such spiritual and romanticized precepts as “balance,” “harmony,” “order,” and “happiness.”12 Spies’s queer vision or (per)version of Bali is in that sense constitutive of the Western imaginary of the paradise island, since many were spellbound by Bali’s traditions as seen through his eyes as a quasi-colonial cultural attaché.

Accordingly, the first images about Bali were all focused on the most spectacular ritual, trance, and mystical aspects of its dance-drama. As part of a colonial visual technology, films like Sang Hyang and Kecak Dance (1926), Calon Arang (1927), Island of Demons (1931), Goonagoona (1932), and Trance and Dance in Bali (filmed in 1939 but released in 1951) helped to promote Bali’s dance-drama as the cornerstone of its exoticism. These films typify the colonial study and consumption of the native through visual and aural representations while pointing to a way in which theatricality, cinematography, and ritual embodiment are central to the spell of the Balinese exotic. The groundbreaking short film Trance and Dance in Bali, for instance, is famous for documenting Balinese dancers in violent trance seizures as they turn their krisses (sharp daggers) against their breasts without injury. It inaugurated the genre of visual anthropology, which rendered a form of native verisimilitude (or “the way things are”) in a simultaneously cinematic and scientific gaze. The shift from written field notes to recorded field images or documentary films was a major methodological move in the twentieth century. Photography and film footage became an important archive as well as a portal to Balinese culture. The idea is that one can infer as much if not more about a culture through careful photography and meticulous filming rather than through written notes.

Though Margaret Mead is widely known as the writer, narrator, coproducer, and codirector of Trance and Dance in Bali, the film was a team effort involving Gregory Bateson (producer/photography), Jane Belo (photography), Katherine Mershon (notes), and Colin McPhee (music), all members of the aforementioned café salon with Spies at the helm. In the film, the viewer is directed by Mead’s narration to focus on the most spectacular trance occurrences from the Calonarang dance-drama. Consider her description of Rangda (the “witch”) and the possessed devotees of Barong (the “dragon”) in a segment known as “Kris Dance”:

These are the dragon’s followers falling to the ground at the glance of the witch, up again when she turns her back, down again when she looks at them. … She trips through their ranks, runs away, and as her back is turned, up they get again, rush to the attack, but as she turns, her glance forces them back, back, back, back, and she stands, back, back, and then turns away, indifferent, this is slow motion, the followers of the dragon with their krisses in the air, ready for the attack, but falling down again before her glance (normal speed), the witch dances again and then two by two, they run up and attack her. She doesn’t resist, she submits as a rag doll, but overcome by her power, they fall and lie in deep trance. Two more come up, fall also. Members of the club come and arrange them on the ground while another pair attacks the witch. They lie arranged in two rows in deep trance, compulsively twitching. And the dragon comes back to revive them, … comes back in a somnambulistic state, comes back in. The witch meanwhile has fallen into a deep trance, and being carried away … (the dance in slow motion).13

As the transcript suggests, Mead is staging a theatrical encounter with Rangda, an archetypal figure in Balinese ritual whom she calls “the witch” and a figure of immense fascination to Westerners, using slow-motion editing and a highly animated commentary. Rangda’s bewitching spells are rendered through her glance, and her attackers are possessed into a deep trance. Even as Mead sought to give an objective and scientific account, the controlled modulations of her voice, the exotic cinematography of the film, and the emphatic repetition of words—“her glance forces them back, back, back, back, and she stands, back, back”—like stage directions to intensify the dramatic account of the trance possession, give her away. The text could well be describing a scene from an occult or horror film. In fact, Mead’s disembodied presence was often more captivating as a vocal performance than the actual ritual spectacle. It also bears note that the trance focus of the documentary was part of a research project funded by the Committee for Research in Dementia Praecox, and a series in “Character Formation in Different Cultures.”

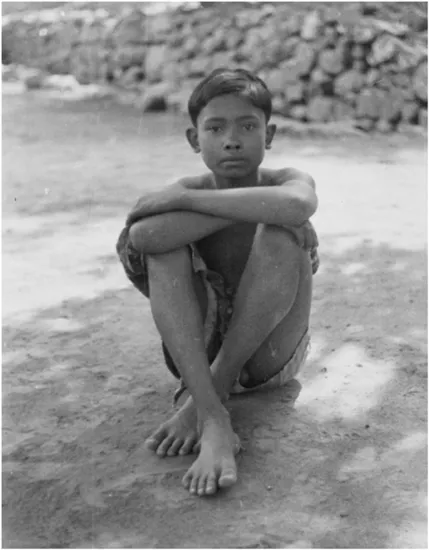

Mead’s “objective” visual approach to advance an intercultural study about the prevalence of possession (or schizophrenia) among the Balinese is in stark contrast to Walter Spies’s relationship with the “Balinese male youth.” Unlike Mead’s approach, Spies’s visualization of Bali is much less interested in the purchase of a scientific façade. Rather, it veered toward art. At the archives of Leiden University in the Netherlands, his unpublished photography includes a large number of solo portrait shots of Balinese men and boys in a variety of languid or martial poses as well as those that capture the ritual possession of kecak dancers with an unmistakable spell of kinetic wonder. The collection blurs the lines between photography and painting, and the way that art is archive and vice versa. As I sat contemplating the images at Leiden, they began casting a different kind of spell, a spell of the onlooker rather than of the subject of the gaze. The spell was on an entranced Spies looking on the boys as they speak back with expressive eyes and wonder not only to him but to me through him in a triadic encounter. This homosexual encounter, like D. A. Miller’s cruising of Barthes’s texts, restages the colonial encounter by queering the Euro-ethnographic hetero-gaze on the native boy, and creates a witty visual repartee or dialogue with “the natives.” For instance, a Balinese man peering out of his mask with a wry smile appears to be playing with Spies, the camera or onlooker. He smiles as if he were well aware of the queer encounter; the peering poses a premonition of a tropic spell that has heretofore been without a name or history.

Figure 1.1

Balinese man peering out from mask.

Leiden University Library, Collection

Marianne van Wessem, shelfmark Or.

25.188-II-46.

Figure 1.2

Balinese man in sampan.

Leiden University Library, Collection

Marianne van Wessem, shelfmark Or.

25.188-II-66.

Figure 1.3

Balinese men in martial pose.

Leiden University Library, Collection

Institute Kern, shelfmark Walter Spies

80-1315.

Figure 1.4

Balinese man in languid pose.

Leiden University Library, Collection

Institute Kern, shelfmark Walter Spies

80-1490.

How to Do a History of the Dyad

To trace the history of the colon...