![]() PART I

PART I

Gender Blending![]()

1

Surgical and Hormonal Creation of the Binary Sex Model

One of the few fundamental aspects of life is that of sex. … To visualize individuals who properly belong neither to one sex nor to the other is to imagine freaks, misfits, curiosities, rejected by society and condemned to a solitary existence of neglect and frustration. … The tragedy of their lives is the greater since it may be remediable; with suitable management and treatment, especially if this is begun soon after birth, many of these people can be helped to live happy well adjusted lives.1

This passage came from a 1960s medical text written by two respected doctors. The sentiments expressed in this book reflect the basis for the standard treatment protocol for infants born with an intersex condition, which began during the 1950s. This chapter examines the development of the dominant treatment protocol for infants with an intersex condition that began in the middle of the twentieth century and remained largely unchanged for fifty years. It examines the unproven assumptions about sex, gender, and disability that have shaped medical practices and describes the recent challenges that call these common practices into question.

Sex Differentiation

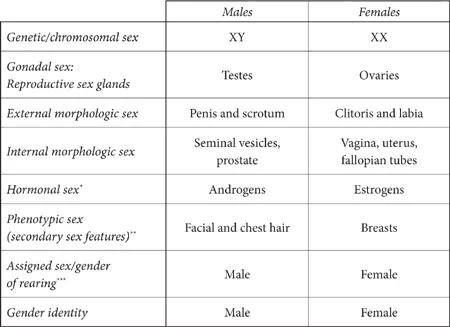

Medical experts now recognize that at least eight attributes contribute to a person’s sex. These factors include genetic or chromosomal sex, gonadal sex (reproductive sex glands), internal morphologic sex (seminal vesicles, prostate, vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes), external morphologic sex (genitalia), hormonal sex (androgens or estrogens), phenotypic sex (secondary sexual features such as facial hair or breasts), assigned sex and gender of rearing, and gender identity.2

The Typical Sex Differentiation Path

During the first seven weeks after conception, all human embryos are sexually undifferentiated. At seven weeks, the embryonic reproductive system consists of a pair of gonads that can grow into either ovaries (female) or testes (male). The genital ridge that exists at this point can develop into either a clitoris and labia (female) or a penis and scrotum (male). Two primordial duct systems also exist at this stage. The female ducts are called Mullerian ducts and develop into the uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper part of the vagina if the fetus follows the female path. The male ducts are called Wolffian ducts and are the precursors of the seminal vesicles, vas deferens, and epididymis.

At eight weeks, the fetus typically begins to follow one sex path. If the fetus has one X and one Y chromosome (46XY), it will start down the male path. At eight weeks, a switch on the Y chromosome, called the testis determining factor, signals the embryonic gonads to form into testes. The testes begin to produce male hormones. These male hormones prompt the genitals to develop male features. Additionally the testes produce a substance called Mullerian inhibiting factor that causes the female Mullerian ducts to atrophy and to be absorbed by the body, so that a female reproductive system is not created.

If the fetus has two X chromosomes (46XX), the fetus’s body develops along what is considered the default path. In the thirteenth week, the gonads transform into ovaries. In the absence of testes producing male hormones, the sexual system develops along female lines. The Wolffian (male) ducts shrivel up. The typical sexual differentiation path is summarized in Table 2.

Variations of Sex Development

Millions of people do not follow the typical sexual differentiation path and they have sex indicators that are not all clearly male or female. A number of variations from the typical sex development path could lead to the development of an intersex condition. This section describes some of the more common intersex conditions; a table summarizing these conditions appears in the appendix. Universal agreement about what conditions should be considered intersex does not exist. Some people believe that the term intersex should apply only to people with ambiguous genitalia or an unclear gender identity. Others have asserted that intersex should refer only to conditions in which the chromosomes and phenotype are discordant.

TABLE 2

Typical Path of Sexual Differentiation

* Although androgens and estrogens are referred to as male and female hormones, respectively, all human sex hormones are shared by men and women in varying levels.

** Phenotypic sex characteristics may vary in different societies. For instance, facial hair in women is more accepted in some cultures and therefore is less associated with maleness. Similarly, the absence of chest hair and facial hair is not necessarily characterized as female in some cultures in which men typically have less facial and chest hair.

*** Assigned sex and gender of rearing are generally the same. Although it is rare, sometimes parents will raise a child in the gender opposite that assigned at birth. In addition, if a child exhibits a gender identity opposite to the sex assigned at birth, parents may begin to raise the child in the new gender role.

Chromosomal Variations

Some individuals have chromosomes that vary from the typical XX/XY configuration. Chromosomal variations include XXX, XXY, XXXY, XYY, XYYY, XYYYY, and XO (denoting a single X chromosome). Two of the more common chromosomal variations include Klinefelter syndrome and Turner syndrome. Men with Klinefelter syndrome have one Y chromosome and two or more X chromosomes. Women with Turner syndrome have only one X chromosome.

Gonadal Variations

Some individuals have neither two testicles nor two ovaries. Variations include ovotestes (a combination of ovarian and testicular tissue), one testicle and one ovary, and streak gonads that do not appear to function as either ovaries or testicles. Pure gonadal dysgenesis is a condition sometimes referred to as Swyer syndrome. Individuals with Swyer syndrome have XY chromosomes but may be missing the sex-determining segment on the Y chromosome. Therefore, fetuses with this condition do not develop fully formed testes. In the absence of functioning testes, the fetus appears female but will not have a uterus and ovaries. Often this condition is not apparent at birth and is not diagnosed until puberty, when the absence of breast development and menstruation leads to a diagnosis.

Hormonal Variations

Some XY fetuses are unable to use the male hormones being produced by their testicles and therefore their bodies do not fully develop along the male path. For example, XY infants with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) have a problem with their androgen receptors. Because their bodies cannot process the androgens being produced by their testicles, these fetuses will develop along the default female path and will form external female genitalia. They will not develop female internal reproductive organs because the Mullerian inhibiting factor produced by the testes will inhibit the growth of the uterus and fallopian tubes. Often the vagina will be shorter than average. Sometimes this condition is diagnosed at birth, but occasionally diagnosis does not occur until puberty. People with CAIS have a female gender identity.

Instead of a complete insensitivity to androgens, some XY fetuses have partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS). Depending on the degree of receptivity to androgens, the external genitalia may be completely or partially masculinized.

The condition called 5 alpha reductase deficiency (5-ARD) results from the body’s failure to convert testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the more powerful form of androgen responsible for the development of male external genitalia in an XY fetus. Individuals with 5-ARD may appear to be females at birth. At the onset of puberty, the increased androgen levels may cause the body to masculinize. If masculinization occurs, the testes descend, the voice deepens, muscle mass substantially increases, and a “functional” penis that is capable of ejaculation develops from what was thought to be the clitoris.

Individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) have XX chromosomes and ovaries. Due to a problem with the adrenal system, the fetus’s body will masculinize. The external genitalia may be more similar to male genitals.

The Medical Determinants of Sex Have Evolved

Although medical experts agree that many factors contribute to a person’s sex, the attributes that have been used to differentiate men from women have varied over time and the issue is still a matter of great controversy.

The Age of the Gonads: Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sex was determined based on a person’s gonads.3 A person with testicles was considered a male and a person with ovaries was labeled female. During this time, scientists understood that male and female embryos begin with the same basic sexual features. They also knew that these sex attributes begin to differentiate in utero and continue to differentiate after birth. By the 1870s, scientists understood that the female fetus’s gonads develop into ovaries and the male’s gonads become testicles.

Although medical experts of this era knew that a variety of anatomical criteria could be used to determine a person’s sex, they decided that the gonads should be the critical marker. Therefore, they declared that people with ovaries were women and people with testicles were men. This singular focus on gonadal tissue, to the exclusion of other known sex attributes, may have been influenced by the critical role that the gonads play in the reproductive process. The “Age of the Gonads” was short-lived. Within fifty years, the focus began to shift to another sex attribute: the genitalia.4

The Age of the Genitalia: 1950s–1990s

By the middle of the twentieth century, medical experts had rejected the gonads as the “true” sex indicator and instead started to focus on the appearance of the external genitalia. Before the 1950s, if a newborn emerged with ambiguous genitalia, doctors would assign a sex to the infant that they believed was most appropriate and they would not otherwise surgically or hormonally alter the child.5 During the middle of the twentieth century, two developments occurred that changed the manner in which medical experts determined sex. First, surgical techniques were developed that made it possible to modify genitalia to what was considered to be a “cosmetically acceptable” appearance. Second, the idea that gender identity was based on nurture and not nature became the conventional wisdom. In other words, most doctors, sociologists, and psychologists believed that children were born without an innate sense of being male or female.6 Physicians developed a treatment approach based on the following three assumptions:

• Infants are born without an innate sense of gender. Therefore, infants can be raised as either boys or girls and they will develop the gender identity that matches their genitalia and the gender role in which they are raised.

• Children who grow up with atypical genitalia will suffer severe psychological trauma.

• A child’s intersex condition is a source of shame and should be hidden from friends, family, and the child.

Thus, beginning in the 1950s, the standard protocol for treating newborns with ambiguous genitalia involved surgical alteration of “unacceptable” genitalia into “normal” genitalia. Normal genitalia for boys required an “adequate” penis. If doctors believed that an XY infant had an “adequate” penis, the child would be raised as a boy. A child without an “adequate” penis would be surgically altered and raised as a girl. The penis became the essential determinant of sex because medical experts believed that a male could only be a true man if he possessed a penis that was capable of penetrating a vagina and allowed him to urinate in a standing position. Medical technology at this time was capable of creating what was considered an adequate vagina (defined as one that was capable of being penetrated by an adequate penis), but the technology was not advanced enough to create a fully functional penis (one that was capable of penetrating a vagina). Therefore, surgeons would typically turn XY infants with small penises or infants with other genital ambiguity into girls.7

Under this protocol, XY infants with smaller penises were surgically and hormonally altered and raised as girls because of the dominant belief that growing up as a boy with an “inadequate” penis was too psychologically traumatic to risk. Some XY infants who had fully functional testicles had their ability to reproduce destroyed rather than having them be raised with a penis that was considered smaller than the norm. XX infants with a phallus that was more similar in length to a penis than a clitoris were treated differently. If they had the ability to bear a child as an adult, doctors would maintain their reproductive capacity. They would surgically remove the clitoris or reduce it to a size that they considered acceptable, even though the surgery might diminish or destroy the person’s ability to engage in satisfactory sex.

In other words, the dominant protocol required that children should only be raised as males if as adults they would be able to engage in conventional sexual acts by penetrating a female’s vagina. For females, however, the primary emphasis was on maintaining reproductive capacity rather than preserving the ability to enjoy sexual acts.8

Because infants with an intersex condition were considered “abnormal,” their birth typically was shrouded in shame and secrecy. Doctors often told parents half truths about their children’s conditions. Parents were also encouraged to lie to their children about the nature of their condition. The children were viewed as “freaks.” Their conditions were to be studied by physicians and hidden from society.

Sherri Groveman Morris’s description of growing up with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome captures the experiences of many people with an intersex condition treated under the standard protocol that began in the 1950s:

Sadly, my parents were not offered any type of emotional counseling to help them parse the distressing fact of having a child labeled, as my medical records show I was, a pseudo-hermaphrodite. Instead my diagnosis was considered a tragic mistake of nature by both my physicians and my parents. Given that I looked normal, however, my parents undoubtedly took solace in that they did not ever have to reveal the truth about my body to friends or relatives, and could keep it a secret even from immediate family members.

Having not had an opportunity to work through their own shame and guilt at having a child born with an intersex condition, my parents were even less able to develop any kind of game plan to disclose the details about such a fact to me. Instead they were advised by my pediatric endocrinologist to tell me I had a simple hernia when, as a young child, I discovered the abdominal scar (from removal of the testes soon after birth) just above my pubic region. They were then to say nothing again until the eve of puberty, at which time they should tell me that I had “twisted ovaries,” which had been removed at birth to prevent them from becoming cancerous. …

By far the most disturbing of my recollections was of being on an examining table while interns and residents “inspected” me, all the while discu...