![]()

1 / The Frontier Ground and Peoples of Northwest China

Well, I at least find myself reflecting on this point. A geographical area keeps a certain flavour, which manifests in all its happenings, its events. . . . I sometimes wonder if this thought may not be usefully taught to children at the start of their “geography lessons.” Or would one call it history?

Doris Lessing, Shikasta

Muslims live almost everywhere in China. A few small clusters are located in the south, more in the northeast, and hundreds of thousands on the north China plain, with the densest concentrations at Beijing and Tianjin, though they constitute only a tiny minority among the non-Muslim Chinese.1 Tens of thousands of Muslims live in Yunnan’s cities and market towns, and smaller numbers may be found along the trade routes leading to Burma and Tibet from the southwest. But Muslims in contemporary China still live most densely along the ancient Silk Road, which connected Central Asia with north China. Eastern Turkestan (now the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region) has had an indigenous population that is almost entirely Muslim and non-Chinese-speaking for centuries, joined only during the past forty years by millions of non-Muslim Chinese.

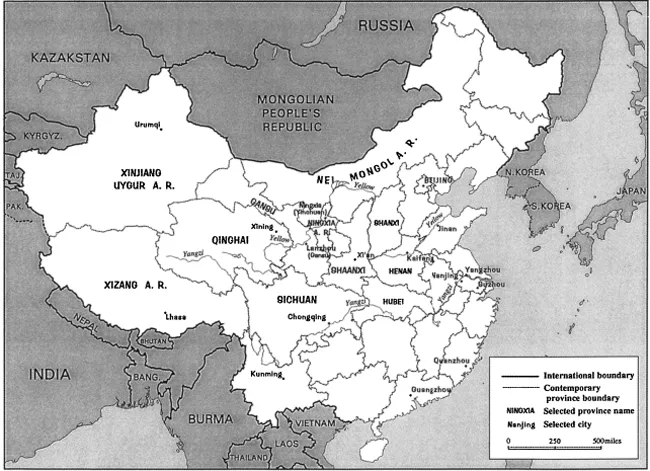

Between north China and Turkestan are two zones of dense Muslim habitation: the Ningxia region of the middle Yellow River valley (now the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region) and a crescent of territory in southwestern Gansu and northeastern Qinghai Provinces. These zones, one on either side of the regional core at Lanzhou, are the ground of most of this book—a frontier of four cultures, a region known in China for little except poverty, marginality, archeological riches, and bellicose inhabitants. Though I must begin with a general history of Islam’s arrival and development in China, since no such narrative exists in English, the lion’s share of this work focuses on the northwest.

MAP 1. Contemporary provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of the People’s Republic of China.

(Map by Philip M. Mobley)

Therefore this book is not about China, but about a particular part of China, a frontier very distant from the core areas of Chinese culture and very strange to most Chinese. That does not, of course, reduce its importance in Chinese history. The distance of the northwestern frontier from “China proper” (which northwesterners call neidi, the interior) enhances its value as a lens on the range and diversity of Chinese life. Local history, not in the mode of case studies in search of the typical but as an understanding of the particular for its own sake, deepens and subtly diffuses our comprehension of what it is to be Chinese. The generalization and homogenization of Chinese society by scholars, both Chinese and foreign, distorts the real and compelling variety created by distinct environments and their particular histories.

The acts recorded by chroniclers of northwest China have tended to be violent and antisocial, construed as immoral by the Confucian judges of history. In a narration of this rowdy past, we must ask why people, often neighbors for years or for generations, take up weapons to kill one another at particular historical moments. What begins what Barbara Tuchman has called “the march of folly,” leading to bloodshed on a small or large scale? It will not do to say, as many have, that Muslims are naturally violent and fanatical people because of their doctrine. Nor can we aver that Chinese people do not care about human life because there are so many of them. Or that frontiers are just violent places. Historians of the particular cannot ignore or devalue the often peaceful Muslims, the often life-affirming Chinese, the often calm fronters. In order to discover patterns and clues in the specific time and place, we must patiently explore what people actually did.

In the civil, avowedly antimilitary and culturally homogeneous China of the dominant mythology, violence may properly serve only the holder of the mandate of Heaven.2 Yet in folk tradition, from the early legends to the battles of Cao Cao to the heroes of the Shuihu zhuan and the Luding Bridge, warfare and martial heroism have vaulted men and women into exalted memory, and many parts of China have dramatic, explosive local traditions of violence going back to the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E–C.E. 220) or even before. A local historian of Jiangsu tells me that there are areas of central China where collective or large-scale violence plays almost no part in history. But to call such places “typically Chinese” ignores not only stereotypically violent frontiers such as the northwest but also counties in Zhejiang, Anhui, and even Jiangsu itself that have rich and troubled traditions of violence. To understand China in its particulars, we must assimilate that violence into our imagery.

Thus we can build on Hsiao Kung-ch’uan’s famous metaphor—China as a vast mosaic of environments and histories. In this book I focus on a small part to discover the colors and textures of its many fragments, their brightness and sharp corners, their diverse shapes. As local history becomes more popular and more viable, a clear vision of the parts must, in our history of scholarship, clarify the complex human effort that created the whole.

FRONTIER GROUND

October 1938. Gu Jiegang was tired and worried. His father was dying back home in Suzhou, but the forty-five year old professor of ancient history knew he could not travel east to do his filial duty. He had been on the road for over a year, having left Beiping just ahead of the invading Japanese, and had arrived in Sichuan only in September, after an exhausting fact-finding tour of the northwest. Not yet ready to report to the Sino-British Cultural and Educational Endowment Fund, which had sponsored his excursion in the hope of learning more about education among the northwestern Muslims, he nonetheless agreed when an old friend asked him to give a lecture. He had to speak to his audience—the faculty and students of the Mongolian-Tibetan School of the Central Political College—in a makeshift hall, for Chongqing’s universities, like its sewers and housing market, had been flooded by refugees fleeing the Japanese:

When Demchukdonggrub [Ch. De Wang] started the autonomy movement in Mongolia in 1933, I met with him and his associates at Bailingmiao. Only after that did I realize the gravity of frontier issues, so I changed my direction and began to study frontier problems. . . . [On my recent trip] most of the places I visited were inhabited by Hui and Fan [Tibetans]. . . . Banditry is a really serious problem there. . . . Though we met with some local desperadoes, fortunately they didn’t rob us.

The most severe and most pressing problem in the northwest is transportation. . . . If you haven’t been there, you couldn’t imagine it, but between neighboring counties, even townships, people rarely communicate. . . . If the northwest’s transportation problem is not solved, there’s no sense even talking about the others.

Of the places I visited, many were districts with complex racial [Ch. zhongzu] and religious intermingling. . . . The Muslims have Old Teaching, New Teaching, and New–New Teaching, while the lamaists have Red, Black, Yellow, and Flowery sects. Among the races there are Han [Chinese], Manchus, Mongols, Hui Muslims, Qiang and Fan, Salar Muslims, and Turen [Monguors, a Mongolic-speaking people]. . . . Because northwesterners have all these factions, all these mental barriers, they know only that there are sectarian divisions, and they don’t know that they all are citizens of the Republic of China!

. . . people from the rest of China rarely go to the northwest, and those who do are all merchants, low-class salesmen, with small minds and love for high profits, who often jack up prices and cheat ignorant Tibetans and Mongols.

The places we went on this trip are actually in the middle of our country’s territory; when people say we got to the frontier, it makes us feel really ashamed. . . . So our responsibility in “frontier work” must be gradually to shrink the frontier, while enlarging the center, so that sooner or later the “frontier” will just be the border.3

We have no record of the audience’s reaction to Gu’s lecture, but he remained convinced that the northwest held one of the keys to China’s future, so he spent much of his career investigating its history. His father died that winter without ever seeing his son again.4

The Frontier Ground of Gansu

Gu Jiegang was right about the northwest’s physical position inside China’s border—the provinces he visited are only slightly north and west of the country’s geographical center, if the vast areas conquered by the Qing are included in “China.” But he was certainly ingenuous about culture. Despite its proximity to the “center” of China, what he called the northwest constitutes the meeting ground of four topographical and cultural worlds: the Tibetan highlands, the Mongolian steppe, the Central Asian desert, and the loess of agricultural north China.5 This frontier zone encompasses the perimeters of cultures that have been in evolving contact on this same ground for centuries. We might have a comparable area in the United States if large numbers of Navajo farmers, Sioux hunters, Anglophone ranchers, and Spanish-speaking herders all had been packed for a long period of time into a three-hundred-mile-square, ecologically diverse region of New Mexico. The comparison between northwest China and the American west did not escape a contemporary Chinese urbanite sent to work in Qinghai during the Cultural Revolution:

The road passed through hills and valleys that were at times bleak and empty, reminding me of what I had imagined the American wild west would look like, based on a movie I had once seen in Shanghai. “Where were the cowboys and the Indians?” I asked myself, and later of course it turned out that I would be one of the cowboys and the Tibetans would be the Indians.6

In physical space eastern Gansu forms the transitional zone between steppe/highlands and arable lowlands, its climate dry and severe, its topographical contrasts sharp and sudden.7 Both of the historically crucial roads in the region—between Central Asia and the cultural cores of China (west-east), and between Tibet (Xizang) and Mongolia (south-north)—pass through the Gansu corridor, the narrow gap between the northern Tibetan mountains and the Mongolian desert.

The complex topography has contributed to equally complex human geography. In historical time, most of Gansu has been numerically and politically dominated by Chinese people and the states ruling them, both the conquest dynasties and the domestic. As Gu noted, sharing or competing with them for the productive and strategic resources of Gansu have been diverse non-Chinese peoples, among them Tibetans sedentary and nomadic (including a few Muslims), Turkic-speakers (Muslim and non-Muslim), Mongolic-speakers (Muslim and non-Muslim), and mixtures among the four. New ethnic identities have evolved as peoples and states advanced, contracted, and mingled along this multicultural margin, strategically crucial to many states but central only to those who live there. Personal and collective identities, elusive and processual in all human societies, have proved particularly troublesome in frontier areas when modern states attempt to rigidify boundaries and classify people; Gansu is no exception.

In central Gansu, at Jiayuguan, lies the symbolic end of the Chinese agriculturalist’s domain, the terminus of the Great Wall. Even inside the wall, however, the Gansu topography dictates a diverse economy, with livestock breeding and trade in animal products playing crucial roles beside cultivation of food grains and artisanal production. The eastern half of the province, with its New England–like climate, produces good tobacco, fruit, millet, and medicinal herbs. Both eastern Gansu and the Gansu corridor have soils and conditions well suited to the opium poppy, planted in great abundance in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Much of Gansu, however, does not look as agrarian China should (see plate 1). The hillsides and grasslands, especially in the high country of the Tibetan mountains and Alashan, provide pasture for sheep, goats, local breeds of hardy cattle, horses, deer, and yaks. Between the river valleys, away from water sources, much of Gansu lies barren, the loess deeply eroded into steep hills without sufficient topsoil or water for agriculture. There the population spreads more thinly across the landscape, and even the best roads wash out in the rainy season or collapse when earthquakes strike. Gu Jiegang knew from firsthand experience how many parts of Gansu, remote from regional or even local centers, remain difficult to reach because of the infrastructural obstacles posed by topography and climate.

Gansu Geographical Regions

The Yellow River, its tributaries, and the deforestation of its watershed have carved out much of this harsh terrain. The rivers—very rapid as they flow down from the high mountains—obstruct transport, irrigate narrow flatlands along their banks, and erode the slopes from which the trees have been removed. They also define the regions into which the province has traditionally been divided. Lanzhou, the provincial capital and commercial and transportation center of the whole region, lies on the Yellow River’s south bank, directly between the...