![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Capital of the Columbia

A HARD GREEN LAND

Mount Hood hovers over Portland like a watchful god.

The iconic view of many cities features a skyline or a manmade feature—an Eiffel Tower, Gateway Arch or Brandenburger Tor, Transamerica Tower or Empire State Building.

In place of cathedral spire or capitol dome, Portland offers its natural setting. “The mountain is out,” we say when the winter clouds clear and Mount Hood shimmers white in the afternoon sun. Snowmelt from the mountain’s northwestern valleys flows pure and untreated through Portland water taps. We worry occasionally, when small tremors shake the still living volcano, that Hood may suddenly erupt as Mount St. Helens did in 1980; geologists have mapped the most likely course of lava and ash flows toward Portland’s eastern suburbs. But usually the mountain is playground and backdrop, silhouetted against a sharp blue dawn on occasional clear winter mornings, tinged pink in summer evening sunsets. “The white mountain loomed like Truth itself, or a bad painting,” was novelist Robin Cody’s capsule summary in Ricochet River.1

Portland’s other icon is roses. Some places may identify with the hard and heavy products of industry as Iron City or Motown. Portland identifies with tens of thousands of rose bushes in city parks and front yards. As early as 1889, lawyer and litterateur C. E. S. Wood suggested an annual rose show. Civic leaders and journalists made Portland the “Rose City” by the new century and were soon promoting an annual Rose Festival, complete with parades, queen, and Royal Rosarians to oversee the festivities. Long after cities such as Denver and Los Angeles have given up their turn of the century promotional festivals, Portland still stages the Rose Festival each June. Bright red roses are painted on the doors of city vehicles, bracketing the slogan “The City That Works.” Even police cars sport their own red rose decals.

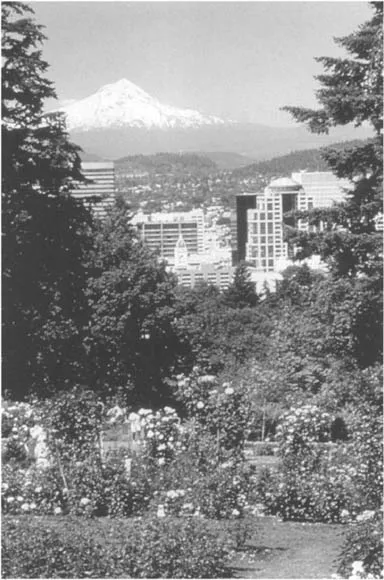

Mount Hood from Washington Park (Livable Oregon, Inc.). Portlanders mark the weather and the seasons by the face of Mount Hood on the eastern horizon—floating over a sea of low clouds or glistening with new snow, backed by the colors of a winter sunrise or bathed in the softer glow of a summer evening.

The common photo for tourist brochures and business promotion booklets combines the two images. Photographers set their tripods in the Washington Park rose gardens just west of the central business district. Roses grace the foreground while downtown buildings frame and support the image of the mountain, made to float over the city through the power of the telephoto lens. Although its peak is fifty miles from downtown Portland, the mountain rises more than 11,000 feet above the city—a greater upward reach than Long’s Peak above Estes Park, Colorado, and only a few hundred feet short of the rise of the Jungfrau over Interlaken. Mike Burton, executive director of Metro, Portland regional government, claims that Portland’s vision for the future can be summed in two phrases: “everyone can see Mount Hood” balanced by “every child can walk to a library.”2

The rose cult(ivation) is a function of the marine climate of western Oregon. Portland lies within the northwestern rain coast that stretches from Mendocino, California to the Alaskan islands, an area whose extremes of weather are defined by wet and dry far more than by cold and hot. Its cousins are other locations on western coasts and in the middle latitudes, where prevailing westerly winds squeeze moisture from maritime polar air masses but where proximity to the oceans moderates the range of temperatures. Portlanders would feel at home in southern Chile, Tasmania, Norway, northern Spain, France, and the British Isles. Its peers are Seattle and Victoria, Wellington and Hobart, Bilbao, Bordeaux, and Bristol. The cult of roses reflects not only the cultural Anglophilia of late nineteenth-century Americans but also a commonality of ecosystems. It is not pure puffery for the wine industry that has developed in Portland’s southwestern exurbs since the 1970s to note that northern Oregon and southern France have the same latitude.

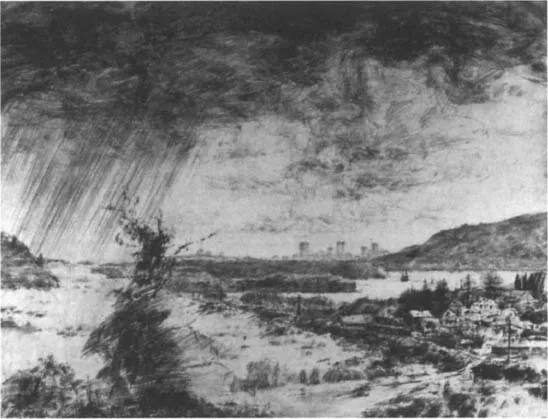

“Wind from the South” (Stephen Leflar, etching, 1984, Visual Chronicle of Portland). Rain in Portland arrives from the southeast with counterclockwise winds from low pressure centers over the Pacific. In the showery season from February to June, bands of rain alternate with clear skies, a weather pattern Stephen Leflar captures in this view southward toward downtown and the west hills.

Portlanders watch the northern Pacific for their weather. The season of storms arrives in late October or November when low pressure builds in the Gulf of Alaska and the jet stream drops southward to sweep across the northern states. The counterclockwise swirl around the deep atmospheric low pumps moist Pacific air across Oregon from the west and southwest, driving ashore band after band of clouds. “Pineapple express” is the shorthand for especially juicy storms of warmer air that pick up moisture from as far to the southwest as Hawaii and drench the valleys and mountains.

Heavy storms abate in February, giving way to a long showery season from February through June. Spring comes early, with crocuses in February and daffodils in bloom by early or mid-March, followed by fruit trees, azaleas, rhododendrons, and then roses in time for the June celebration. Sunny days alternate with days of clouds and rain, sunny hours with showers, balmy weeks with chilly weeks as late as May. Spring flowers last for weeks in the cool and damp.

The sun comes out and stays in July, August, September, and into October. A ridge of high pressure builds northward from California, displacing the winter low and pushing the jet stream over Canada. The prevailing clockwise winds are now from the northwest, bringing cool but relatively dry marine air to chill the Oregon coast and filter up the Columbia River to Portland. Only 6 percent of Portland’s precipitation falls in the summer. At 46 degrees north latitude (the same as Frederickton, New Brunswick), Portland is scarcely the land of midnight sun, but summer light lasts appreciably longer than in the American heartland along the Ohio River or Chesapeake Bay.

Cool, dry summers and wet, mild winters combine to give northwestern North America the greatest conifer forests in the world. Deciduous trees in natural stands are confined to lowlands, stream margins, and other moist and sheltered sites. The coastal mountains and Cascades are covered with thick forests of hemlock, cedar, noble fir, and Douglas fir. Waxy needles conserve water in the dry summer; conical crowns take maximum advantage of oblique winter sunlight for continuing photosynthesis. The Northwest’s conifers have a 1000 to 1 margin in timber volume over its deciduous trees.

The last weeks of dry summers can also bring fierce forest fires. When high pressure drifts southwest from central Canada and stalls over Idaho, the hot, dry air of the continental interior pours through the Columbia River Gorge, pushing Portland temperatures through the 90s and over 100. Hot haze settles in over the city and house-holders wish for air conditioning, a rarity in all but the newest houses.

When the heat persists, dry brush in forest understories can feed wind-fanned blazes. Embedded in the community memory of Portland is the Tillamook Burn of August 1933, when friction from a log chain torched 400-year-old forests in the Coast Range west of Portland. The 1933 fire burned for twenty-three days and ravaged 240,000 acres. Repeated fires in 1939, 1945, and 1951 consumed the baked snags and sticks and added new acres for a total burned-over district of 352,000 acres. The state acquired the desolate lands in the 1940s. Historian Robert Ficken remembers “the truly awesome Tillamook Burn” from trips between the Willamette Valley and the coast in the 1950s: “For mile after mile, the Wilson River Highway [Oregon 6] offered bleak backseat views of ash, blackened snags, and ruined trestlework.”3 Between 1950 and 1970, 25,000 school children helped replant the burn and fixed the story of fire, community effort, and regeneration in popular memory. “Plant trees and grow citizens” was the slogan. Oregon poet William Stafford reflected years later on the devastation:

These mountains have heard God;

they burned for weeks. He spoke

in a tongue of flame from sawmill trash

and you can see His word down to the rock.4

Fires notwithstanding, the most common understanding of Portland’s climate is grayness. Because the sunny weeks of August lack even the drama of lightning storms, it is the low winter sky that attracts notice—the gray blanket of drizzle, the short winter light. Clouds are great gray sponges wrung out against the west slope of the Cascades. The winter weather can nourish deep depression. But the gray months can also be soothing, muffling, twilight weather, thinking weather. Portlanders outpace most of the nation in magazine subscriptions. They are avid bookworms and science fiction fans who spend 37 percent more than average Americans on reading matter. In the nineteenth century Portland jurist Mathew Deady famously described his city as the place whose “good citizens will sleep sounder and live longer than the San Franciscans.”5

Portland writers freight the rain with larger meanings. David James Duncan offered up the rain as comforter in The River Why (1983): “It was the first good rain since the August showers. . . . A rain that hummed on the river pool and pattered on new puddles. . . . I was lulled and cradled, caressed and enveloped in a cool, mothering touch. . . . I realized that I had been given a spirit-helper: I had been given this rain.”6 In Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” drifting sand and time are the great levelers. “I am the grass. Let me work,” wrote prairie-born Carl Sandburg to invoke the power of nature over vanity. Rain does the same work in William Stafford:

“MY PARTY THE RAIN”

Loves upturned faces, laves everybody,

applauds tennis courts, pavements; its fingers

ache and march through the forest numbering

limbs, animals, Boy Scouts; it recognizes

every face, the blind, the criminal,

beggar or millionaire, despairing child,

minister cloaked; it finds all the dead

by their stones or mounds, or their deeper listening

for the help of such rain, a census that cares

as much as any party, neutral in politics.

It proposes your health, Governor, at the Capitol;

licks every stone, likes the shape of our state.

Let wind in high snow this year

legislate its own mystery: our lower winter

rain feathers in over miles of trees

to explore. A cold, cellophane layer,

silver wet, it believes what it touches,

and goes on, persuading one thing at a time,

fair, clear, honest, kind—

a long session, Governor. Who knows the end?7

Northwestern America is storm coast as well as rain coast. Portland’s location promises a reliable cycle of violent weather, a regular harshness that stems from the hydrologic cycle of the North Pacific. Duncan’s soft rains of early October soon give place to pelting coastal gales. Equinoctial gales roar up the Willamette Valley every fall. The Columbus Day storm of 1962, with hurricane force winds, is remembered each anniversary. January ice storms coat the roads and trees when the wet marine air collides with continental cold at the mouth of the Columbia River Gorge, shutting off the lights and closing down highways and runways.

It is no accident that Oregon writers choose storms as the introductions and pivots of their great regional novels. Cold driving rains control the coastwise trek of an old mountain man in Don Berry’s Trask (1960). A torrential downpour launches the wanderings of young Clay Calvert in H. L. Davis’s Pulitzer prize novel Honey in the Horn (1935): “Even to a country accustomed to rain, that was a storm worth gawking at.” Sometimes a Great Notion (1964), Ken Kesey’s sprawling novel about independent loggers on the Oregon coast, begins with water: “Along the western slopes of the Oregon Coastal Range . . . come look: the hysterical crashing of tributaries as they merge into the Wakonda Auga River.” Hank Stamper battles the surging river year after year to save his family’s waterfront house. When everyone else has moved sensibly uphill, he armors the riverbank like a battleship: “The house protrudes out into the river on a peninsula of its own making, on an unsightly jetty of land shored up on all sides with logs, ropes, cables, burlap bags filled with cement and rocks, welded irrigation pipe, old trestle girders, and bent train rails. . . . And all of this haphazard collection is laced together and drawn back firm against the land by webs of rope and log chain.”8 He carries on family tradition by logging the watershed of the Wakonda Auga, as defiant of labor unions and large corporations as he is of the river. At the book’s climax, Hank watches helplessly as Joe Ben Stamper lies pinned in the river under a log that jumped the wrong way, waiting for the turning tide to fill his lungs.

Kesey and Davis and Berry remind their readers of the constant dangers of the recreational environment. Portlanders are safe from Texas tornados and Carolina hurricanes, but they die each year trying to enjoy the outdoors. They capsize while rafting and kayaking rivers that flood with unanticipated rains and snowmelt. They drown while swimming in suburban streams that are far less placid than their surfaces. They die on the Pacific beaches, pulled to sea by sneaker waves or crushed under huge snags shifted suddenly by the surf. Ten thousand people scale Mount Hood each year, but climbers perish in avalanches and whiteouts and missteps on rotten snow. They slip on damp trails and mossy rocks and fall to the water-slicked rocks below. They venture to the forest on bright October days to cut firewood and die when wind snaps a snag or swings a chainsawed tree in an unexpected direction.

Western Oregon has always been a land of physical challenge. Oregon Trail pioneers of the 1840s who reached The Dalles in October faced a painful choice before they could gain the promised Eden of the Willamette Valley. They could pick a way around the south side of Mount Hood before snow and mud closed the passes or lash together unwieldy rafts to launch into the rapids of the rain-swollen Columbia. The last hundred miles to the Willamette Valley could take a month of sodden misery.

The environs of Portland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a land of rugged loggers, mill hands, railroad crews, bindle stiffs, Scandinavian gillnetters, and Chinese salmon cannery workers (until they were displaced by packing machines known as Iron Chinks). There were Finnish socialists in Astoria, homegrown populists in Portland, and a scatte...