![]() II

II![]()

3 Changing in the Gymnasium

Greek history begins, traditionally, with athletics. The date calculated in antiquity for the first Olympic games, 776 BC, has been held to divide prehistory from history.1 The earliest Greek literature, too, dating from the late eighth or early seventh century, has Greeks competing in games. Book twenty-three of the Iliad tells of a chariot race, boxing, wrestling, running, armed fighting, throwing a lump of iron, archery, and javelin throwing at the funeral games of Patroklos; book eight of the Odyssey has the Phaiakians holding games involving running, wrestling, jumping, discus throwing, and boxing; Hesiod’s Works and Days tells of poetic competition at the funeral games of Amphidamas. By the end of the sixth century there was an established festival circuit, involving games at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia (the “Crown games” as they came to be called) that were open to all Greeks. When Kleisthenes of Sikyon wanted a suitable husband for his daughter Agariste, the woman who would become the mother of the Athenian constitutional reformer Kleisthenes, Herodotos tells that he advertised at the Olympic games and then tested the suitors by prolonged athletic competition.2

1. Athletics at Athens: The Civic Investment

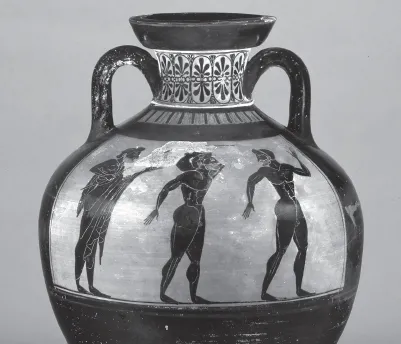

At Athens, athletic activity had been part of formal civic life at least from the second quarter of the sixth century, when the festival of the Great Panathenaia was reorganized.3 Part of this reorganization involved rewarding victors and runners-up in athletic events with olive oil in distinctive “Panathenaic” amphoras.4 These amphoras were decorated with an image of Athena on one side and an athletic scene on the other (3.1).5 The earliest show scenes of running, of three events of the pentathlon (discus, javelin, jumping), and of equestrian competitions. Boxing and running in hoplite armor appear in the third quarter of the century, and by 480 the full range of athletic activity is shown. Victors seem most probably to have received amphoras that showed a selection of events, rather than simply the event in which the prize was won, and so these variations may indicate which images were popular (either with painters or with consumers), rather than which events were part of the program.6 Indeed, after circa 470, equestrian events disappear from the amphoras for about a century, even though there is much evidence that they continued to be held. Panathenaic amphoras continued to be produced in the black-figure style long after that style had ceased to be used for most other pots, a rare material manifestation of institutionalized cultic archaism.

Figure 3.1. Panathenaic amphora, height 0.635 m, late sixth century. British Museum 1852,0707.1 (B 136). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

By the early fourth century, the Athenians were awarding as many as 140 amphoras of oil to the winner of just one event, the two-horse chariot race, and a total in excess of 2,000 amphoras seem to have been given as prizes in the year (circa 370) from which part of an inscribed record survives.7 This at a time when an amphora of oil was worth at least twelve drachmas. By the same date cash and other prizes were being awarded in the musical competitions and sacrificial cows in the team events (armed dancing, torch race, boat race).8 In the late fifth century the total state expense on the Great Panathenaia certainly exceeded five talents and may have been well in excess of nine talents.9

The individual competitions at the Panathenaia were not restricted to Athenians. Athletes were attracted from all over the Greek world, and the distribution of the findspots of Panathenaic amphoras has reasonably been taken broadly to reflect this, although there is some evidence that suggests that there were collectors of Panathenaic amphoras.10 But the team events at the Panathenaia were restricted to Athenian citizens. We do not know at what date the team events were first included, but in the classical period the Kleisthenic tribes were the basis for team membership (except for the armed dancers [pyrrhikhistai]11), so these events must have been reorganized, or indeed created, after the Kleisthenic reforms of 507. At least one of these events, the pyrrhic dance, seems to have featured at the Lesser (that is, annual) as well as the Great (that is, quadrennial) Panathenaia, and the same may be true of the torch race.12

No other Athenian festival seems to have had athletic events for individuals, but team competitions were quite common. The addition of competitive team events to existing festivals, and the creation of new festivals including competitive events, is particularly a mark of the years immediately after the introduction of democracy.13 Eventually team torch races, for example, were a feature of the Aiantea, Anthesteria, Apatouria, Epitaphia, Hephaestea, Promethea, Thesea, festival of Pan, and festival of Bendis as well as of the Panathenaia (although in several cases the earliest attestation of the race is late in the Hellenistic period), but only in the Panathenaia were pots given as prizes.14

The Athenians also awarded top-up prizes to Athenian athletes who won at Olympia and the other pan-Hellenic festivals. These awards were held by the Athenians to have been instituted by Solon, and there can be no doubt that they go back at least to the sixth century, but they were reiterated in the late fifth century.15 In offering victorious athletes civic hospitality at the prytaneion, the Athenians treated them as major public benefactors. This was in line with the widespread practice of according victors in pan-Hellenic competitions a special place in warfare.16

2. Athletics at Athens: The Ideology

Recognition by the city was the formal counterpart to popular support. That support is manifest in the way that individual men may be identified in both historical and oratorical texts as “the wrestler” or “the runner of the stadion.”17 And it had political consequences, both in the archaic and in the classical period. The stories of Kylon’s attempted political coup in the late seventh century lay stress on his having been an Olympic victor.18 Herodotos’s story of the relations between Peisistratos and his sons and Kimon son of Stesagoras emphasizes Kimon’s repeated chariot-racing victories at Olympia: even ascribing his victories to the tyrant does not buy Kimon off; appropriately when he is assassinated it is with his horses that he is buried.19 More remarkably, Thucydides has Alkibiades, more than a century later, parade before the democratic assembly his unprecedented Olympic success in 416, when chariots he financed achieved first, second, and fourth places, as grounds for the Athenians supporting him in his views about the invasion of Sicily.20 In the fourth century, too, athletes could be chosen as ambassadors or political leaders: the Arkadians sent Antiokhos the pankratiast as their representative to negotiations to renew the King’s Peace in 367, and the author of [Demosthenes] 17 claims that Alexander had set up a wrestler, Khairon, as tyrant in Pellene.21

But the Athenians notoriously figure rather seldom in epinician poetry—just two odes of Pindar and one fragmentary ode of Bacchylides—and commentators have wondered whether “the disadvantages of prestige display of an overtly individualistic kind were especially felt in democratic Athens.”22 Outside Alkibiades’s speech, athletic prowess, and even the contribution to a victory in a tribal or team event, is not something that we find boasted about in surviving speeches, whether speeches in the assembly or speeches in the Athenian law courts—though the presence of one Isthmionikos (Mr. Isthmian Victor) among the signatories to both the Peace of Nikias and the Athenian alliance with Sparta (Thuc. 5.19.2, 5.24.1) suggests that some Athenian families were not backward in advertising their athletic achievements.23 More generalized expectations are displayed when Xenophon has Socrates get Charmides to agree that, for someone who is able to win honor and glory for his city by victory in one of the Crown games, not to compete would be to show himself “soft and cowardly.”24

What does get mentioned by Athenians keen to make a good impression is the sponsoring of athletic events.25 Litigants in court told the jurors not only about their generous funding of the navy as a trierarch or of the Dionysia, Lenaia, or Thargelia, with their tragedies, comedies, and dithyrambs, as a khoregos, but also about the athletic events they had sponsored. Financial support was required for various team events—pyrrhic dancing, the torch race, the boat race to Sounion. The famously generous defendant of Lysias 21 had financed all of these events; elsewhere we find Andokides mentioning that he was gymnasiarch at the Hephaistia, Demosthenes that he was responsible for a chorus (either dithyrambic or pyrrhic) at the Panathenaia, and the speaker of Isaios 5 that he was responsible for a pyrrhic chorus.26 It remains notable that the torch and boat race make so little impact, and given the way that the liturgy system worked it seems quite likely that those who knew they would have to spend money in liturgies preferred to sponsor drama, dithyramb, or dancing, rather than races. The only sculptural celebration of such liturgical activity that we know, the so-called Atarbos base, celebrates a victory with pyrrhikhistai.27

Alkibiades’s willingness to boast of his equestrian successes causes surprise not simply because there would seem to be no logical connection between the ability to pay for the best horses, trainer, and drivers for chariot racing, and wisdom in determining Athenian foreign policy. It i...