![]()

ONE

Remembering Yi Sihang, a Local Elite of Significance

This chapter offers an in-depth description of Yi Sihang’s personal and familial connections and networks. I naturally introduce the names of many people who were mostly not figures of high achievement, not characters of dynastic importance, and thus not known in the general history of Korea. Yet they were members of a family, a village, a lineage, and a larger regional elite community to which they were necessarily tied and related, socially and culturally. Without naming these people who have been ignored as unworthy and thus erased from historical memory, their lives cannot be reconstructed and tracked down in meaningful ways. I therefore examine “trivial” writings such as short biographies (haengjang), tomb stele inscriptions (myogalmyŏng), and genealogies. These types of writings are inevitably private, and possibly skewed to glorify the persons and families written about. Yet they can also be seen as “public” in that they were written with the idea that someone else would eventually read them. Although northern genealogies in particular have been criticized as fraudulent, careful readers can find obscure clues in them that lead to hidden meanings and a better understanding of the cultural contexts and social milieu in which the persons concerned lived. These records can thus shed considerable light on social and cultural lives at the individual, familial, and local levels.

Remote Ancestors

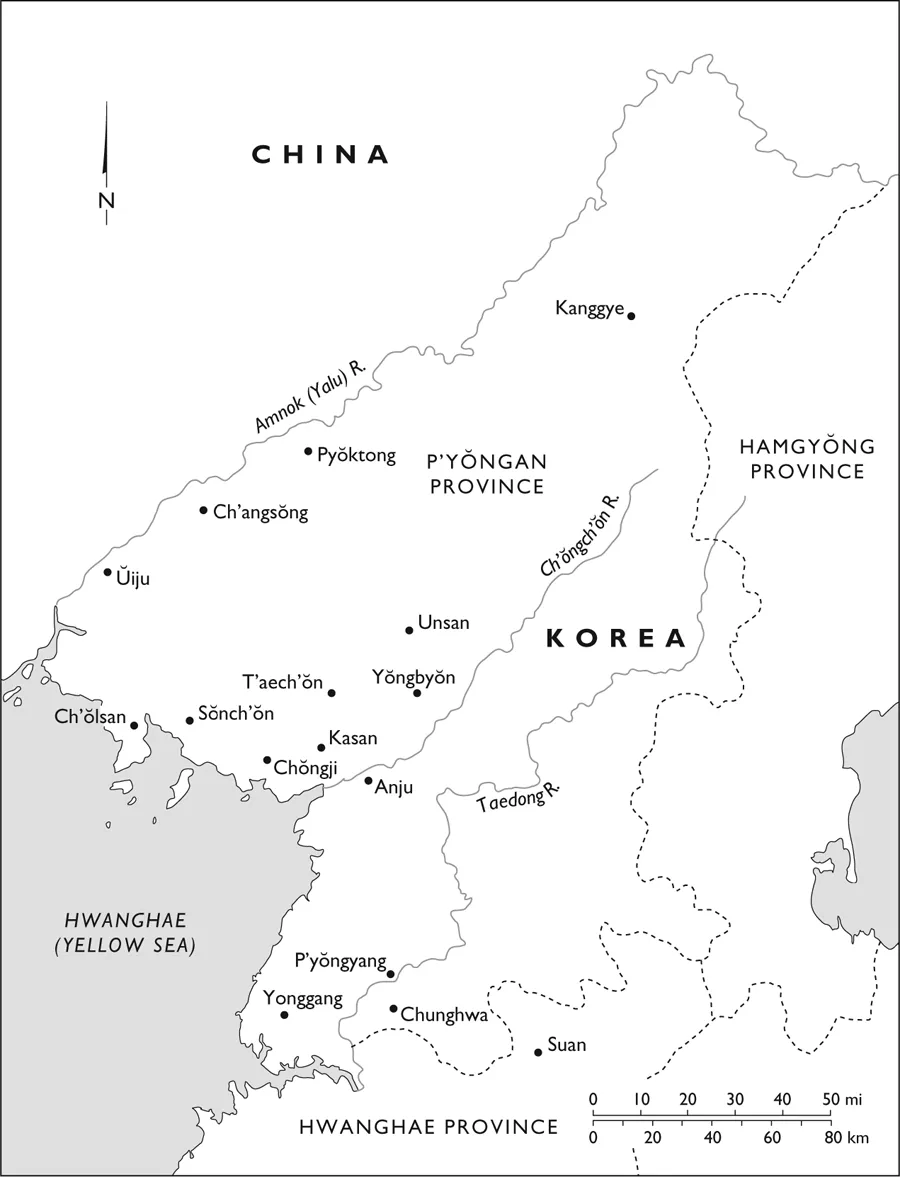

Yi Sihang was born on 1672.10.20 to the Suan Yi descent group residing in Unsan, P’yŏngan Province (see Map 2). Members of the Suan Yi descent group have long claimed that their apical ancestor is Yi Kyŏnung, who was designated a “merit subject” (kongsin)—the highest honor awarded by the Koryŏ court—after assisting Wang Kŏn (877–943; King T’aejo, r. 918–943) in unifying the country and founding the Koryŏ dynasty.1 Yet it seems there is no historical record that bears the name of this ancestor and verifies his accomplishments. It is also unclear what Yi Kyŏnung’s clanseat (pon’gwan) was, because the clanseat of Suan originated from Yi Yŏnsong (?–1320), who served three Koryŏ kings—Ch’ungnyŏl (r. 1274–1308), Ch’ungsŏn (r. 1298 and 1308–1313), and Ch’ungsuk (r. 1313–1330)—and who earned the title of Lord of Suan (Suan-gun) in the early fourteenth century.2 Yi Yŏnsong is a historical person, for his name appears several times in the History of Koryŏ (Koryŏsa). He was apparently a native of Suan (in Hwanghae Province in Chosŏn), which was originally a hyŏn but was upgraded to a kun in recognition of his merit.3 He earned fame for his loyalist death on behalf of King Ch’ungsŏn.4 Much later, in 1662, he was enshrined in the Yonggye Academy (Yonggye sŏwŏn) in Suan, which received a royal charter in 1708. Yi Sihang recorded the history of this royal chartered private academy, in which he illustrated Yi Yŏnsong’s lofty character, spread of Confucian scholarship, benevolent administration, and loyal death.5 Other ancestors whose names can be verified from historical records are Yi Inu, who commanded troops against the Red Turbans in 1358,6 and Yi Susaeng, one of the seventy-two Koryŏ loyalists who refused to acknowledge and serve the new Chosŏn dynasty but hid in Tumun-dong, Kyŏnggi Province after the fall of Koryŏ in 1392.7

Three prominent scholar-officials in the late Chosŏn lent prestige to earlier editions of the Suan Yi genealogy by writing prefaces to them, in which they also acknowledged the historical origin of the Suan Yi descent group from Yi Yŏnsong.8 Kim Yu (1653–1719) wrote a preface to the 1715 edition when he was the governor of Hwanghae Province. A recognized disciple of Song Siyŏl (1607–1689) and Pak Sech’ae (1631–1695), Kim Yu was a good friend of Yi Sihang (see Appendix A) and later assumed the position of director (taejehak) of the Office of Royal Decrees (Yemun’gwan) and of the Office of Special Councilors (Hongmun’gwan), one of the most prestigious bureaucratic positions in Chosŏn Korea.9 In the preface, Kim mentions that he himself is related to the Suan Yi lineage through his maternal line (oeye), and praises the family for knowing the value of genealogy and unstintingly underwriting the publication of its genealogy.10 The preface to the 1781 edition is by Nam Hyŏllo (1729–?), the headmaster (taesasŏng) of the Royal Confucian Academy (Sŏnggyun’gwan) at the time. Nam was a descendant of Nam Chae (1351–1419), a merit subject for his assistance in the founding of the Chosŏn dynasty, whose maternal line was from the Suan Yi. Nam recognizes that the Suan Yi is a renowned lineage from ancient times and that its clanseat originates with the Lord of Suan.11 Hong Sŏkchu (1774–1842), the director of the Office of Special Councilors at the time, is the author of the preface to the 1832 edition. Hong notes that this edition consists of twenty-two volumes, making it more extensive than any other prominent lineage, and attributes the growth of the Suan Yi lineage to the virtue (tŏk) accumulated by its progenitor, the Lord of Suan, who died for the king. Hong’s connection to the Suan Yi lineage came from his grandfather Hong Naksŏng (1718–1798), who was the director of the aforementioned Yonggye Academy, the royal chartered private academy where the Lord of Suan was enshrined.12

Map 2. P’yŏngan Province during the late Chosŏn dynasty

All three authors mention that they initially declined the requests from Suan Yi members to write a preface to the genealogy. In the case of Hong, he turned down several requests before he agreed. It was very common for lineage representatives to seek a preface and/or postscript to their genealogy from high court officials and renowned scholars, who often declined such requests, whether courteously or disdainfully. It is nevertheless unusual for the Suan Yi lineage to have these three very eminent scholar-officials agree to write a preface. Apparently, its members successfully called on friendship and blood relations as well as intellectual connections, no matter how remote. In the late Chosŏn period, a written genealogy was not just a record of a family’s past and present but an important site of memory—one that defined the status of its commemorators, as well as of the living members of the lineage, at the time of compilation. The greatness of ancestors, whether invented or not, affected the status of their descendants. A genealogy is clearly a private record, yet its public nature cannot be overlooked. Thus these prefaces written by renowned public figures had the effect of authenticating the history and honor of this lineage.

As Hong Sŏkchu remarks in his preface, the branches of the Suan Yi lineage grew in number, with the majority of descendants of the Lord of Suan moving out of Suan to other parts of the Korean peninsula, in particular to P’yŏngan and Hwanghae provinces, from which twenty-three out of twenty-six Suan Yi munkwa passers emerged during the Chosŏn dynasty.13 Yet, although their numbers increased, the Suan Yi did not do well in establishing themselves as central elites. Yi Yŏnggyŏn, whose place of residence is unknown, earned his munkwa degree in 1429—the only person from the Suan Yi to do so before the seventeenth century.14 The social and political downfall of the Suan Yi lineage in the early Chosŏn period may have had to do with the loyalist position taken by its late Koryŏ ancestors.

The revival of the lineage—which in any case failed to raise the family to prominence—was spearheaded by the branch that moved to Unsan, which in 1652 produced the first munkwa passer since Yi Yŏnggyŏn in 1429, followed later by five more munkwa passers.15 It was Yi Sindong, a grandson of Yi Susaeng, who began to reside in Unsan after he was banished for a “trivial” crime he committed during the reign of King Sŏngjong (r. 1469–1494), when the policy of population relocation (samin) was very strict.16 Late Chosŏn northerners often recalled that it was the early Chosŏn relocation policy that had led their ancestors to the land they made their adopted home, and the Suan Yi descent group in Unsan is no exception.17 As was often the case for move-in ancestors (iphyangjo) who founded a new residence removed from their original clanseat, Yi Sindong does not appear in any other historical sources. Genealogical records on Yi Sindong’s son and grandson also cannot be verified from other sources, leaving the traces of family history murky until the early seventeenth century, and thus making the connection between late Koryŏ figures and those in the seventeenth century uncertain. Although the compiler of the 1683 Suan Yi genealogy notes that most family records were lost during the Japanese (1592–1598) and Manchu (1627 and 1636) invasions, there is room to doubt that Yi Sihang and his descent group were an offshoot of the lineage of Yi Yŏnsong. However, if the family origin of Unsan’s Suan Yi descent group was in fact very obscure, it would have been impossible for its members to forge marriage ties with established local elite families in Chŏngju, Yŏngbyŏn, and even P’yŏngyang from the seventeenth century on. As noted earlier, members of the Suan Yi lineage probably did not fare well politically because of its ancestors’ loyalty to the preceding dynasty, and thus did not leave historical records traceable in the seventeenth century, when its descendants tried to reconstruct the history of their progenitors in the early Chosŏn period.

Unsan

Unsan (Figure 2) is located in northern P’yŏngan Province, north of Yŏngbyŏn and northeast of Chŏngju, along the Ch’wi River, a tributary of the Ch’ŏngch’ŏn River. It was a county, a garrison (chin), or a part of another county during the Koryŏ and the early Chosŏn periods, and was finally designated a county under the supervision of a junior fifth grade magistrate (kunsu) from the early fifteenth century on, except for a few years between 1459 and 1462. Being located in the mountainous inland region of northern P’yŏngan Province, Unsan was difficult to reach and its land was very barren, able to support only about a hundred househol...