![]()

1

The Rise and Fall of Equity Research at Prudential

In the span of twenty-six years, the insurance giant Prudential entered and then exited the stock brokerage industry. Prudential’s story illustrates many of the changes and challenges facing the equity research industry during this period. Like many competitors, Prudential entered the industry as part of a “financial supermarket” strategy. Lured by attractive fees, Prudential subsequently built an investment banking business leveraged through equity research. The firm was also among the first to recognize the conflicts of interest between equity research and banking, and voluntarily closed its investment banking business prior to regulatory changes created to mitigate such conflicts. The resulting business model focused on providing investors with trustworthy investment advice and trade execution. However, this model was tested by sharp declines in trading commissions brought about by electronic trading. As a result, despite having a highly ranked equity research department, Prudential exited the industry in June 2007.

Insurance History

Prudential Insurance Company was founded by John Dryden in 1875 to provide life insurance to working-class families. The company was named after Prudential Assurance Company of Great Britain, a pioneer in industrial insurance on the other side of the Atlantic. The company quickly developed a reputation for financial stability, inspiring the well-recognized symbol “The Rock.”

During the 1970s, Donald MacNaughton, Prudential’s chief executive officer (CEO), encouraged employees to think of Prudential’s business as selling, not just providing, insurance. This approach led Prudential to expand into auto and homeowners’ insurance. MacNaughton believed that Prudential’s continued prosperity could be assured only by leveraging the firm’s selling capabilities and finding new ways to serve policyholders.1 Insurance was certainly one component of a customer’s financial needs, but there were many others. MacNaughton and his successors worried that unless Prudential could broaden its product offerings, other financial services firms could capture a portion of their customer base by offering a broad array of financial services through a single distribution network.

The Acquisition of the Bache Group Inc.

In early 1981, the Bache Group was looking for help. For two years, management had been trying to fend off a hostile takeover attempt by First City Financial, a Canadian financial services company owned by the Belzberg family. The family had acquired more than 20 percent of the company despite defensive maneuvers by Bache management, and most insiders considered the takeover virtually inevitable.2 However, Bache’s CEO, Harry Jacobs, had one last plan—in February 1981 he launched a search for another potential acquirer.

Garnett Keith, a senior vice president, was the first person at Prudential to be contacted about acquiring Bache. Keith reported, “I received a phone call from Bob Baylis at First Boston, and he asked me if Prudential would like to acquire Bache. And I said well, not likely, but let me talk to the chairman. So I went and talked to Bob Beck, and he thought about it and was quite enthusiastic.”

At the time, Bache was primarily a retail brokerage firm serving individual customers, although not a very prestigious one. An analyst recruited to the firm recalled his first weeks on the job:

Bache was headquartered at 100 Gold Street, which was one of the seediest, most disgusting buildings in Manhattan. The furniture looked awful, and the orange carpeting was worn down to its last few threads. It was not a place to which you’d want to bring anyone you were trying to impress. Bache had a poor reputation among institutional investors, and it had no investment banking that anyone could see. It did have a large retail sales force, but it often seemed in bad spirits, was not terribly successful, and was not well respected. During my first few months at Bache I recall moments when I found myself staring at my rotary-dial telephone and feeling as if I was back in the nineteenth century.

Despite Bache’s marginal position in the industry, Beck saw the acquisition as a way to jump-start Prudential’s “financial supermarket” strategy. The goal was to turn Prudential into a one-stop shop for all of a customer’s financial service needs. Beck understood that the quality of Bache’s products (especially its equity research) would have to be improved, but he also envisioned a day when insurance agents would sell mutual funds and brokers would sell life insurance. Keith explained why Beck was so confident that Prudential could effectively harness these synergies:

Bob Beck was a consummate marketing executive. He had run Prudential’s agency organization and was very confident in his ability to manage people selling products on commission. What he saw in Bache was another commission-driven sales organization that additional products could be put through. At the time, Bache clearly had mediocre products and therefore was not able to attract and hold top talent. Beck felt that Prudential could upgrade Bache’s product and then could attract and hold a better quality of financial advisors, which is what really drives business.

Others, like Fred Fraenkel, a former research director at the firm, were more skeptical and harbored doubts as to whether Prudential understood the complexities of the stock brokerage industry. He explained:

Prudential was a really large mutual insurance company that had tens of millions of lives insured. It was based in Newark and run by insurance company executives whose motto was “perpetual and invulnerable.” That had little to do with returns or profitability or cost or policyholders. “You give me money, you’re going to die, I’m going to pay your policy face amount.” What assures that? That we’re perpetual and invulnerable. So they had a view of the world that didn’t really have anything to do with what went on in the rest of the financial services continuum.

In March 1981, Prudential Insurance Company of America offered $385 million to acquire Bache Group Inc. The deal was consummated the following year. Although Bache had a small investment banking operation, there were no plans to grow that business. Keith explained why:

The investment side of the Prudential organization was quite concerned that if we owned something that had even a fledgling investment banking operation, it was going to foul up our relationships with the bulge-bracket (most prestigious) investment banks that were necessary to keep our cash flow invested. Through the whole acquisition process, less was more. Less investment banking made it more attractive to Prudential. The last thing we wanted was investment banking activity over at Bache that could potentially ruin a much more important cash investment process at Prudential, the parent. Investment banking was a concern, not an attraction.

New Management at Bache

Shortly after the acquisition, Prudential began looking for someone to lead the new company, renamed Prudential-Bache Securities, or PruBache for short. In 1983, George Ball was hired. At the time, Ball was second-in-command at E. F. Hutton, a highly successful retail brokerage firm. Fraenkel described him as an exceptional motivator:

He was the son of the superintendent of schools of Milburn, New Jersey, a speed reader, a very high-IQ person, a very dynamic person, who had spent his career in a meteoric rise through E. F. Hutton on the retail side of the firm. The thing he was unbelievably good at was personnel management. E. F. Hutton was like Bache, it had several thousand brokers, and he knew every broker’s name, and he knew every broker’s wife’s name, and he knew every kid of every broker and what school they were at. George was a memory-system person; he had “mental compartments” where he could literally memorize thousands of items and recall them instantly. He would ask people personal questions, and everyone felt they were his best friend. He was probably one of the best cheerleader-managers that I’ve ever been around.

Ball’s first priority was to develop the institutional side of the business—to build a research department and a sales and trading organization that could service large institutional investors such as mutual and pension funds. He believed these important capabilities could then be leveraged to develop other businesses. To lead the effort, he looked to his former colleagues. Mike Shea, former president of Prudential’s equity group, remembered:

The first big move was the joining of Greg Smith, Fred Fraenkel, and Ed Yardeni from E. F. Hutton. They came in as the strategy trio. And their mission was to begin the formation of a true institutional business. A lot of institutional salespeople followed from E. F. Hutton and a couple of other places to Pru in the early ’80s because they wanted to be involved in the business with them. So that was really the very beginning; that was the genesis.

The “strategy trio” had some success in accomplishing their goals. Pru-Bache began to service institutional clients and started to leverage their new capabilities to better service retail clients as well. Soon the focus turned to investment banking.

Project ’89: The Genesis of Investment Banking at Pru-Bache

In the years immediately following the merger, little was done to improve Bache’s small investment banking business because of the potential impact on the Prudential Insurance Company’s Wall Street relationships. Keith recalled that the decision to expand Pru-Bache’s business was undertaken to “internalize some of the investment banking fees that were being paid to the bulge-bracket firms.” Prior to May 1, 1975, trading commissions had been regulated, generating fees that covered the costs of trade execution and equity research. However, the May Day deregulation was followed by a steady decline in commissions, reducing the resources available for research.

In 1987 Ball officially launched Project ’89, investing close to $200 million over the following two years to attract top new investment banking professionals.3 The plan was to build one of the best investment banking operations by 1989. Keith, who was present at the executive committee meetings where the project was approved, commented:

George (Ball) convinced Bob Beck that he should be allowed to build a better investment banking organization. And what he sold Bob Beck was to be the “best of the rest”—that he knew he’d get his head kicked in if he took on Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and First Boston, but he needed to be at least as good as PaineWebber. So the franchise and the funding George got from the Prudential board with Bob Beck’s blessing was to upgrade Bache’s investment banking activity to equal the “best of the rest.”

Prior to Project ’89, Pru-Bache’s investment banking business ranked well behind those of the bulge firms. Furthermore, its current investment banking professionals were not terribly impressive. Therefore, from the outset it was decided that a serious effort to develop investment banking would require new blood. As Investment Dealer’s Digest put it, ultimately “Project ’89 was about hiring, and about spending top dollar to do so.”4 Pru-Bache hired aggressively in all of its divisions: Thirty senior investment bankers joined the firm in the first five months of the project. These professionals were brought in to develop the firm’s relationships with Fortune 500 companies in hopes that associations with big companies would translate into large fees and increased visibility.5

Pru-Bache recruited most of their new investment bank and research analysts from elite firms, in the hopes of competing against them. The compensation packages offered during Project ’89 became legendary. Not only were the salaries and bonuses higher than those paid by many bulge firms, but they were usually guaranteed—not tied to individual or firm performance.6 A research analyst at a bulge-bracket firm approached by Pru-Bache during Project ’89 commented:

Honestly, they didn’t have a lot to offer me. Pru-Bache was a firm with a terrible reputation. It had an investment bank that was in the building stage but had no real presence and no track record. So what they had to offer was, essentially, money. From my perspective, this simply wasn’t a big enough incentive to move. At that time, I was an Institutional Investor–ranked analyst. The research director at my firm did not want to lose me. When he heard about Prudential’s offer, he matched it and I stayed put.

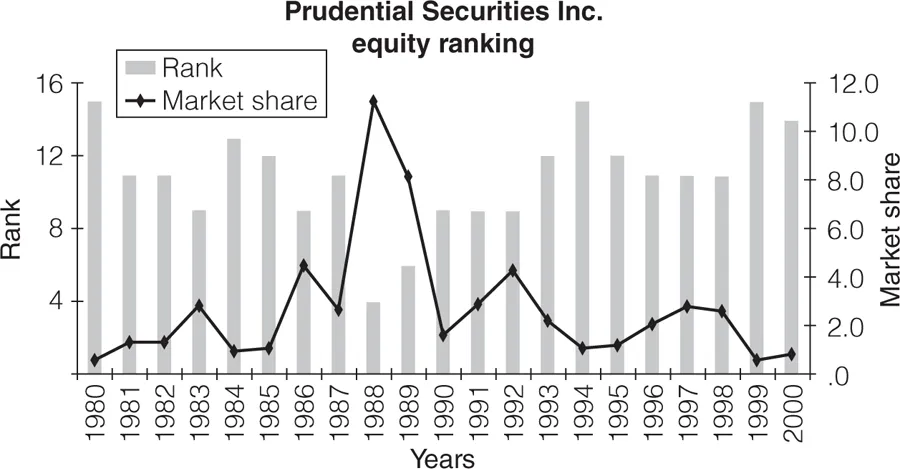

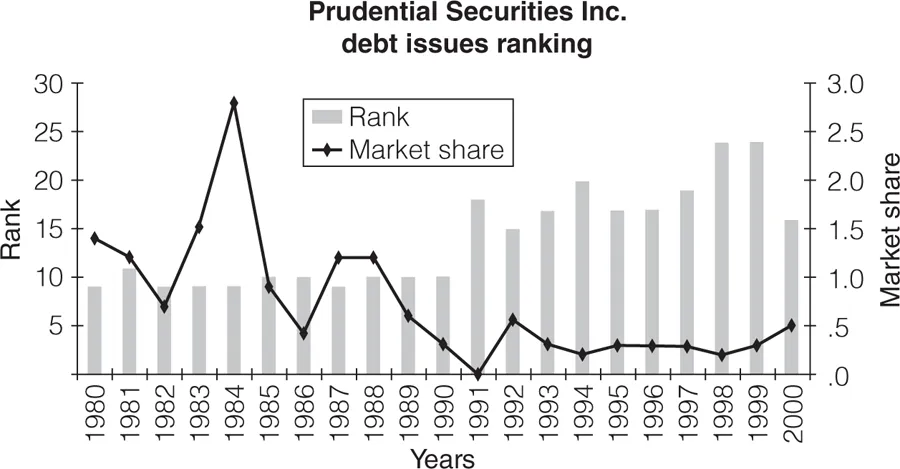

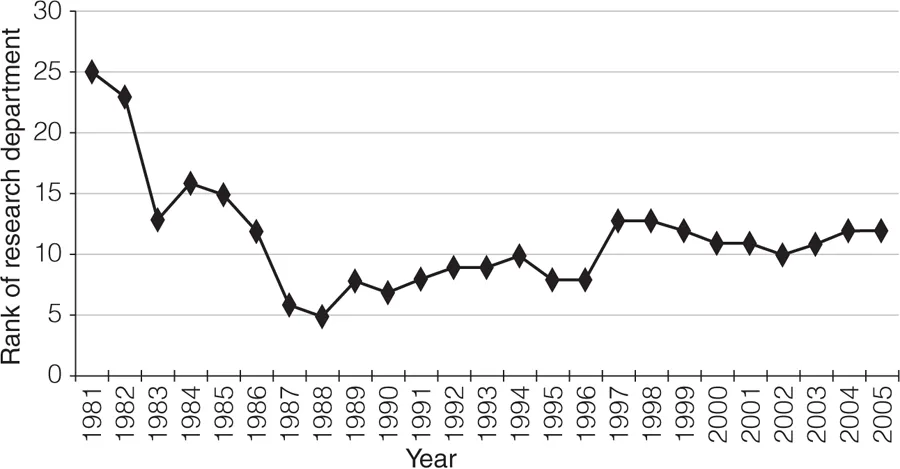

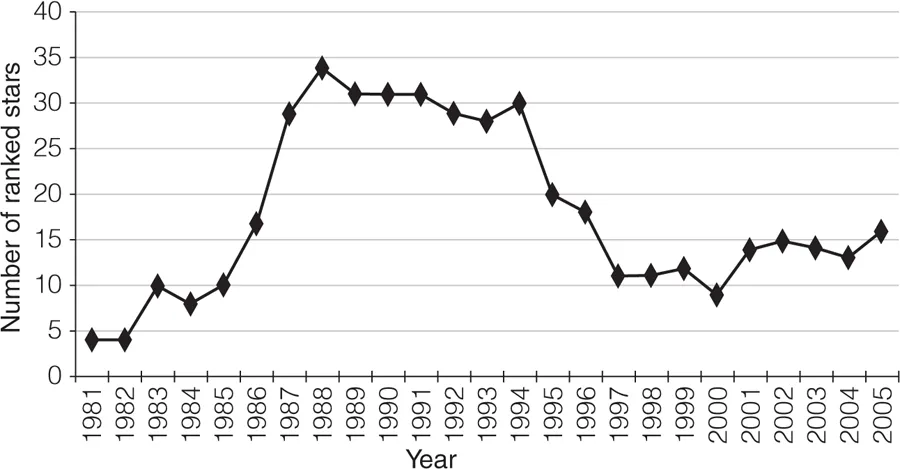

At first, Project ’89 appeared to yield positive results (Exhibit 1.1). Prudential-Bache represented Rupert Murdoch in his bid for the Herald & Weekly in Australia and completed the Reliance Electric Company management buyout—at the time, one of the largest leveraged buyout divestitures ever done. Its equity underwriting market share rose by over 10 percent, and its ranking shot up from eleventh in 1987 to fourth in 1988. Prudential-Bache’s research department also began to move up in the Institutional Investor rankings (institutional clients’ rankings of research departments). By 1988, it was ranked number five with nearly thirty-five ranked analysts (Exhibit 1.2).

Exhibit 1.1. League tables history: Prudential Securities’ market share, 1980–2000.

SOURCE: Thomson Financial DATABASE: U.S. Common Stock (C).

The ’87 Crash and the Demise of Project ’89

On October 19, 1987, the stock market plummeted, losing more than 20 percent of its value. The crash had a serious impact on all banks, but it hit the fledgling Pru-Bache especially hard. Investment banking deals disappeared, and retail commissions dried up due to falling investor confidence. The following year, Prudential Insurance cut funding for Project ’89. Pru-Bache stopped recruiting and let go more than 25 percent of its banking professionals. In 1988, there was a bright spot when the firm completed the Diamandis management buyout of the CBS magazine division. Unfortunately, the market correction of 1989 followed soon after. Pru-Bache posted losses of $50 million in 1989 and $250 million in 1990.7 In early 1991, George Ball resigned.

Exhibit 1.2. Performance of Prudential’s research department.

NOTE: “Ranked stars” are defined as analysts who receive a “First Team,” “Second Team,” “Third Team,” or “Runner-Up” designation from Institutional Investor.

SOURCE: Compiled from Institutional Investor, from October 1981 through October 2005.

There was some controversy over just what caused the project’s failure. Clearly the stock market crashes were part of the reason—revenues dried up while Pru-Bache’s compensation commitments were fixed. However, some maintained that Prudential Insurance Company effectively killed the project by reneging on its financial commitment before all the necessary personnel were in place.8 In fact, many pointed to instances in which Prudential failed to support ...