![]()

Chapter One

HOW TO IDENTIFY A COTTON BOOM

THOUGH HISTORIANS HAVE NOT IDENTIFIED the Iranian plateau as a region of economic dynamism, urban expansion, or manufacturing for export in the pre-Islamic period, it became the most productive and culturally vigorous region of the Islamic caliphate during the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, only a century and a half after its conquest by Arab armies.1 The engine that drove this newfound prosperity was a boom in the production of cotton.

In the eleventh/fifth century the cotton boom petered out in northern Iran while the agricultural economy in general suffered severe contraction. At the same time, Turkish nomads for the first time migrated en masse into Iran. These developments resulted in long-term economic change and the establishment of a Turkish political dominance that lasted for many centuries. The engine that drove the agricultural decline and triggered the initial Turkish migrations was a pronounced chilling of the Iranian climate that persisted for more than a century.

Such are the major theses of this book. Though the argumentation to support them will concentrate on Iran, their implications are far-reaching. Iran’s prosperity, or lack thereof, affected the entire Islamic world, and through its connections with Mediterranean trade to the west and the growth of Muslim societies in India to the east it affected world history. The same is true of the deterioration of Iran’s climate. Not only did it set off the fateful first migration into the Middle East of Turkish tribes from the Eurasian steppe, but it also triggered a diaspora of literate, educated Iranians to neighboring lands that thereby became influenced by Iranian religious outlooks and institutions, and by the Persian language. These broader implications will be addressed in the final chapter, but first the substance of the two theses, which have never before been advanced, must be argued in some detail.

If the evidence to back up the proposition that Iran experienced a transformative cotton boom followed by an equally transformative climate change were abundant, clear, and readily accessible, earlier historians would have advanced them. So what will be presented in the following pages will be less a straightforward narrative than a series of arguments based on evidence that may be susceptible of various interpretations.

With respect to the latter thesis, the cooling of Iran’s climate, the crucial evidence is clear, but it only recently became available with the publication of tree-ring analyses from western Mongolia. The question in this case, therefore, is not whether scientifically reliable data exist, but whether or to what degree information proper to western Mongolia can be applied to northern Iran over 1500 miles away. This question, along with a variety of corroborative information, will be addressed in chapters 3 and4.

The case for an early Islamic cotton boom, on the other hand, rests on published sources that have long been available. However, these sources only yield their secrets to quantitative analysis, as will be seen in this chapter and the next. The methodology of applying quantitative analysis to published biographical dictionaries and other textual materials constitutes a third theme of this book.

In 1970, Hayyim J. Cohen published a quantitative study of the economic status and secular occupations of 4200 eminent Muslims, most of them ulama and other men of religion. He limited his investigation to those who died before the year 1078/470.2 Overall, he surveyed 30,000 brief personal notices in nineteen compilations that are termed in Arabic tabaqat, or “classes.” These works are generally referred to in English as biographical dictionaries. The subset of notices that he extracted for quantitative analysis were those for whom he found specific economic indicators—to wit, occupational epithets like Shoemaker, Coppersmith, or Tailor—included as part of the biographical subject’s personal name. All the compilations Cohen used covered the entire caliphate from North Africa to Central Asia. None was devoted to a specific province or city, except for a multivolume compilation specific to the Abbasid capital of Baghdad.

Commercial involvement with textiles, Cohen found, was the most common economic activity indicated by occupational epithets, and from this he inferred that the textile industry was the most important economic mainstay of the ulama in general. For individuals dying during the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, textiles accounted for a remarkably consistent 20 to 24 percent of occupational involvement. He does not specify which epithets he included in the “textiles” category, or the relative importance of each of them, but the master list of trades that accompanies his article includes producers and sellers of silk, wool, cotton, linen, and felt, along with articles of clothing made from these materials. (Whether he classed furs with textiles or with leather goods is unclear.)

Cohen’s sample amounted to only 14 percent of the total number of biographies he surveyed because in an era before surnames became fixed and heritable, individuals were distinguished by a variety of epithets (e.g., place of origin or residence, occupation, official post, distinguished ancestor), some chosen by themselves and some derived from the usage of others. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the occupational distribution of the 14 percent identified by the name of a trade roughly mirrors the economic profile of the entire 30,000. Scholarship on Islamic subjects, by and large, was not a highly remunerative activity in the Muslim societies prior to the twelfth/sixth century. So most Muslim scholars, unlike Christian clergy supported by the revenues of churches or monasteries, had to earn a secular livelihood to maintain their families. To be sure, the son of a prosperous trader or craftsman who had the leisure to become highly educated in religious matters might have taken the occupational name of his father without himself engaging in the trade indicated, but it seems unlikely that he would have adopted an occupational name entirely unrelated to his or his family’s position in the economy. Whether at first or second hand, then, the abundance of textile-related names, as opposed to the total absence of, say, Fishers or Potters, almost certainly reflects the broad economic reality of the class of people included in the biographical dictionaries.

Cohen’s study provides a baseline against which to compare a parallel analysis of a large biographical compilation devoted to a single city, the metropolis of Nishapur in the northeastern Iranian province of Khurasan.3 With a population that grew from an estimated 3000 to nearly 200,000 during the period of Cohen’s survey, Nishapur was one of the most dynamic and populous cities in the caliphate, probably ranking second only to Baghdad itself.4 Compiled in many volumes by an eminent religious scholar known as al-Hakim al-Naisaburi, this work survives today only in an epitome that contains little information beyond the names of its biographical subjects. But that is sufficient for our purposes.

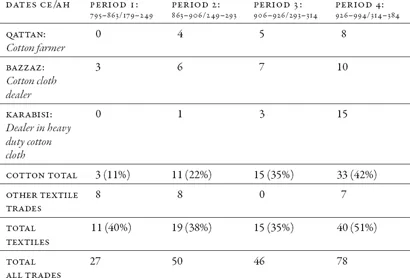

Table 1.1 shows that in each of the periods covered, the proportion of individuals engaged in basic textile trades in Nishapur (“Total Textiles”) is 50 to 100 percent higher than the proportions uncovered by Cohen for the caliphate in general. The dominant role of textiles in the economic lives of Nishapur’s religious elite would have loomed still larger if tailors and vendors of specific types of garments had been included, but they have been left out, since it is uncertain which of them may have been included in Cohen’s calculations.

TABLE 1.1 Occupational epithets in al-Hakim’s Ta’rikh Naisabur

Looking specifically at the tenth/fourth century, cotton growers and cotton fabric vendors alone accounted for 35 to 42 percent of all occupational epithets in Nishapur. This elevated level was noted by Cohen: “As for cotton, the biographies of Muslim religious scholars indicate that Khurasan province was a big centre for its manufacture.”5 This preponderance of cotton farmers and merchants is all the more striking in view of the absence on the table of any cotton growers at all down to the final third of the ninth/third century. In other words, if Iran really did experience a transformative cotton boom, as is being argued here, it would seem to have reached Nishapur only in the late ninth/third century. As we shall see later, however, other types of data show that cotton began to become a major enterprise farther to the west, in central Iran, a century earlier.

Also of interest is the fact that during Period 1 of table 1.1, which immediately preceded the apparent start of the boom in Nishapur, five of the people dealing in textiles other than cotton traded in felt, a commodity produced mainly by nomads in Central Asia and imported into Iran by caravan. This hint that Central Asian imports still dominated Nishapur’s fiber market in the early ninth/third century is reinforced by the fact that there are also five fur merchants recorded for the period. (Since I am not certain whether Cohen considered fur a textile, I have not included furriers in the table.) In sum, felt and fur, two products coming from beyond Iran’s northeastern frontier, together made up 30 percent of all textile/fiber commerce conducted by Nishapur’s religious elite before the rise of cotton.

The occupational preferences of Nishapur’s ulama apparently changed from imported felts and furs to locally produced cotton. The data from Period 3 covering the last third of the ninth/third century, 863 to 906/250–315, confirm this shift . Cotton was then clearly emerging as a major new product, going from 11 percent to 22 percent of all trade epithets, but three felt merchants and two furriers are still recorded for this period. However, during Periods 3 and 4, covering the period down to the start of the eleventh/fifth century, felt dealers disappear from al-Hakim’s compilation, with only one furrier mentioned. Imported fibers were no longer of major interest to Nishapur’s religious elite.

For the skeptically inclined reader, deducing a cotton boom from the changing percentages of occupational names distributed among a couple of hundred religious scholars may seem strained. But leaving precise numerical calculations aside, cotton clearly became an important part of the Iranian economy during the early Islamic centuries. The comparison with Cohen’s data indicates a role for cotton in Iran that was far greater than that played by all textile production combined in the caliphate as a whole, particularly considering that if he had chosen to systematically exclude Iranians from his tabulations, his total for non-Iranian ulama involvement in textile trading would have been appreciably lower.

An even more striking attestation to the historical significance of cotton’s emergence as a key product in the Iranian agricultural economy, however, is the fact that little or no cotton seems to have been grown on the Iranian plateau during the Sasanid period prior to the Arab conquests of the seventh/first century.6 The soundness of this statement is fundamental to the argument of this chapter. Hence, the evidence on which it is based needs to be explored in some detail.

Although at least one scholar, Patricia L. Baker in her book Islamic Textiles, has asserted that large quantities of cotton were exported from eastern Iran to China before the rise of Islam,7 The Cambridge History of Iran takes a more cautious position: “The study of Sasanian textiles … is hampered by an almost total lack of factual information. The meagerness of the historical sources is matched by the paucity of textile documents.”8 The discussion that follows this introductory sentence deals extensively with silk and secondarily with wool. Cotton is nowhere mentioned.

Nevertheless, Baker’s statement refers to trade with China and to “eastern Iranian” provinces that may have been outside the borders of the Sasanid empire. In fact, evidence from east of the Sasanid frontier, which roughly coincided with the current frontier between Iran and Turkmenistan, does confirm the presence of cotton cultivation there, but it falls well short of indicating large-scale production or trade. Moreover, it strongly implies links with India rather than with the Sasanid-ruled Iranian plateau.9

Archaeologists have dated some cottonseeds excavated in the agricultural district of Marv, northeast of today’s Iranian border, to the fifth century CE, and cotton textiles have been found in first-century CE royal burials of the Kushan dynasty in northern Afghanistan.10 At the other end of the Silk Road, there are occasional Chinese textual references to cotton “from the Han dynasty [ended 220 CE] or later,”11 ...