![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE READER

Abraham Lincoln was of the seventh generation of Lincolns in America, descended from a weaver from Norfolk, England, Samuel Lincoln, who became a modestly successful merchant in Hingham, Massachusetts, whose eleven children dispersed to Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Virginia, and a number of whose descendants became distinguished and affluent. Amos Lincoln, participant in the Boston Tea Party, lieutenant colonel of the Massachusetts artillery in the Revolutionary War, and who married successively two of Paul Revere’s daughters, was the father of Levi Lincoln, the leading Jeffersonian of Massachusetts, member of Congress, U.S. senator, Thomas Jefferson’s attorney general and secretary of state, and then governor. As a lawyer he argued the case in 1783 in which slavery was ruled illegal in Massachusetts. His son, Levi Jr., became governor, too, and Abraham Lincoln would eventually meet him in 1848, introducing himself to his illustrious and distant relative, “I hope we both belong, as the Scotch say, to the same clan; but I know one thing, and that is, that we are both good Whigs.”

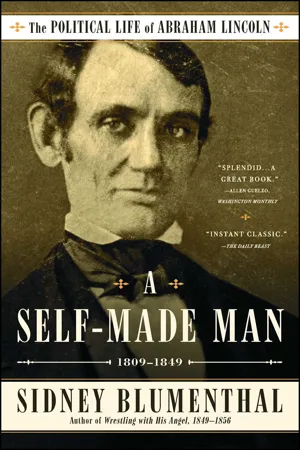

![]()

Thomas Lincoln

![]()

John Lincoln, a great-grandson of Samuel, left his well-to-do family in New Jersey, where his father, Mordecai, owned land and foundries, for Pennsylvania and then Virginia, buying a large expanse in the fertile Shenandoah Valley. He deeded his son, Abraham Lincoln, a tract of 210 acres of the rich Valley land. A captain in the Virginia militia during the Revolution, Abraham appeared to have been inspired by the adventure stories of his distant relative by marriage, Daniel Boone, and trekked through the Cumberland Gap to stake a claim to even more extensive farmland. (The genealogical web linking the Lincoln and Boone families was tightly woven, with four intermarriages between them.) Abraham was well positioned to establish himself among the most prosperous first families of Kentucky, securing 3,200 acres of the best land. But he was ambushed by Indians and killed in 1786. His youngest son, eight-year-old Thomas, barely escaped being snatched as a captive when his older brother, Mordecai, shot the Indian. According to the law of primogeniture still in effect, Mordecai inherited Abraham’s entire estate and was elevated into the Kentucky gentry—slave owner, racehorse breeder, and member of the legislature. Nothing was left to Thomas or his other brother Josiah.

Thomas’s two older brothers were in fact half brothers, offspring of an earlier marriage. After his father’s murder, his stepmother abandoned him, his dead mother’s relatives reluctantly took him in, and he was left to fend for himself as “a wandering labor boy,” as his son would later put it. Working for an uncle in Tennessee, Isaac Lincoln, a planter who owned dozens of slaves, Thomas picked up tradecrafts as a carpenter, mechanic, and farmer, working side by side with his uncle’s slaves. He accumulated enough money, some of it possibly a loan from his half brother Mordecai, to purchase 238 acres in Hardin County, Kentucky, which he leased to a sister’s husband.

Apprenticed at the carpenter’s shop of Joseph Hanks, he spent much of his time at the home of Hanks’s aunt and uncle, Rachel Shipley and Richard Berry, who were the guardians of Hanks’s sister, Nancy. Berry was a fairly well-to-do farmer, with six hundred acres, thirty-four cattle, and three slaves. Rachel was the sister of Nancy’s mother, Lucy Shipley, who had run off with her second husband, Henry Sparrow. Nancy’s father, said to be one James Hanks, or Joseph Hanks, has never conclusively been identified. Some have claimed that Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks were cousins, his mother the older sister of her mother.

Stories of Nancy’s illegitimacy were widespread in the area and by several accounts Lincoln believed it. He once referred to his grandmother as “a halfway prostitute” and admitted “that his relations were lascivious, lecherous, not to be trusted.” Rumors were rife that Nancy was “loose,” even that she had an illegitimate child.

“Billy, I’ll tell you something, but keep it a secret while I live,” Lincoln confessed, riding on the legal circuit with his law partner, William Herndon. “My mother was a bastard, was the daughter of a nobleman, so called, of Virginia. My mother’s mother was poor and credulous, and she was shamefully taken advantage of by the man. My mother inherited his qualities and I hers. All that I am or hope ever to be I get from my mother. God bless her. Did you never notice that bastards are generally smarter, shrewder and more intellectual than others? Is it because it is stolen?” Lincoln’s story as he told it contained the themes of a classic fairy tale, an Old World tale of a pauper who is really a prince, a romance substituting for squalor. The poor boy is unrecognized as the natural-born offspring of aristocracy, possessing not only nobility of lineage but also of mind. But the point of the story was more than compensation for shame or revelation of true aristocracy as a happy ending. The bastard’s child, it turns out, must survive by his wits, what he naturally possesses, not what he’s lost, somehow “stolen.” The would-be fairy tale ends with a twist, the boy creating his past out of dim recollections he has heard about a far-off place he can never regain, as he is inventing himself.

Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks were married in 1806 in a ceremony conducted by a friend of the groom, Jesse Head, a Methodist circuit rider, man of God, and jack-of-all-trades—assistant county judge, local newspaper editor, and cabinetmaker. According to the testimony of a neighbor, the local doctor, Christopher Columbus Graham, the Lincolns were “just steeped full of Jesse Head’s notions about the wrong of slavery and the rights of man as explained by Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine.” Neither of them could write, though they might have been able to read a little, but it is improbable that they read anything by Jefferson or Paine, and instead were likely influenced by what they heard from Head. He was vehemently and vociferously antislavery, later breaking away from the regular Methodist Church over the issue to join the Radical Methodists.

Antislavery agitation had roiled Hardin County, especially its churches, since settlers poured through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky after the Revolution. Slavery was not incidental but central to its life and economy. In 1811, there were nearly as many slaves in the county as white men—1,007 slaves, compared to 1,627 white males older than sixteen. Living in Elizabethtown, young Thomas Lincoln in 1787 was hired as a laborer constructing a mill, working alongside slaves, whose wages were collected by their masters. The price of free labor competed directly with that of slave labor, driving his wages down.

At the mill he was paid no more than the slaves. Like other white men, he was inducted into the local slave patrol to catch runaways, presumably the men he worked with, serving a three-month stint.

The year Thomas helped build the mill a new preacher, Reverend Joshua Carman, appeared at the Elizabethtown Baptist Church, “an enthusiastic Emancipationist,” according to a chronicler of the Kentucky Baptists. The next year Carman founded the South Fork Church, pressing the local Baptist association to stand against slavery. “Is it lawful in the sight of God for a member of Christ’s church to keep his fellow-creatures in perpetual slavery?” he demanded. Failing to receive a satisfactory answer, “fanatical on the subject of slavery, he induced Rolling [South] Fork Church to withdraw from the association and declare non-fellowship with all slave holders.” Though the congregation decided to return to the association in 1802, Carman was hardly discouraged from evangelizing against slavery. Finally, he and another pastor, Josiah Dodge, split off to form a new “Emancipationist” church in nearby Bardstown, “the first organization of the kind in Kentucky.”

In 1807, eleven “Emancipationist” ministers and nine churches in Kentucky created their own antislavery organization, the Baptist Licking-Locust Association Friends of Humanity, which soon organized an Abolition Society. The new preacher in the pulpit at the South Fork Church, William Downs, “was one of the most brilliant and fascinating orators in the Kentucky pulpit in his day,” and he was every bit as antislavery as his predecessor. In 1808, Downs, an “Emancipationist,” was expelled by the pro-slavery majority of the church, which passed a resolution “not to invite him to preach” and branded him “to be in disorder.” Downs was only one of a number of antislavery ministers in Kentucky expelled from their pulpits. He led a group of dissidents to form the Little Mount Separate Baptist Church. David Elkins, another strong antislavery preacher, was also a pastor there. Thomas and Nancy Lincoln, who had belonged to the South Fork Church, left with Downs and joined the new church. Their Knob Creek farm ran close to the Old Cumberland Trail, a principal transportation route between Louisville and Nashville, regularly used by slave dealers moving their human cargo to markets west and south. Undoubtedly, the Lincolns observed the never-ending coffles of enchained blacks marched near their cabin.

The Lincolns’ first child, Sarah, was born in 1807, Abraham on February 12, 1809, and a second son, Thomas, soon after, but who died in infancy. The parents brought Sarah and Abraham regularly to church services, where they almost certainly heard, along with Primitive Baptist preaching, hollering, and hymn singing, vigorous sermons against the wickedness of slavery. Parson Elkins especially befriended the bright little boy. Young Abraham was taught to read and write at what he called an “ABC school.” One of his teachers, Caleb Hazel, was the Lincolns’ next-door neighbor, and a member of the antislavery Little Mount Church. Thomas Lincoln was the groomsman at Hazel’s wedding, a service performed by Reverend Downs. Lincoln described the formation of his views on slavery as among his earliest memories in a letter to A. G. Hodges, a newspaper editor in Frankfort, Kentucky, on April 4, 1864. “I am naturally antislavery,” he said. “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel.”

On January 1, 1815, a suit was filed to evict Thomas Lincoln from his farm. Claims, surveys, and deeds in Kentucky were remarkably hazy at the time. He had a written contract, paid a fair price and taxes, but lacked a proper deed. A wealthy Philadelphia-based absentee landlord asserted ownership of 10,000 acres of Kentucky real estate, including the tiny Knob Creek property, citing Lincoln as defendant and attaching his income for years of supposed back rent. In June 1816, the trial was postponed for two years. Thomas continued to contest and would even win the case, but he did not know that he would. So he decided to cross the Ohio River into Indiana, admitted that year into the Union as a free state. He had felt under attack from all sides. “This removal,” Lincoln recounted to Scripps, “was partly on account of slavery, but chiefly on account of the difficulty in land titles in Kentucky.” Before leaving, Nancy brought her son to pray at the grave of his lost brother, Thomas.

Thomas Lincoln had to hack his way through dense forests and brush to enter the land of promise. For two months, the family huddled in a half-enclosed tent open on one side to wind, rain, and cold, spooked at night by the cries of wild animals, before moving into a rough one-room cabin they built. A year later, they were joined by Nancy’s aunt and uncle Thomas and Elizabeth Sparrow, who had been ejected from their Hardin County farm by the same sort of lawsuit that bedeviled the Lincolns. They brought with them Elizabeth’s nephew, Dennis Hanks, a cast-off child, born illegitimate, whose real last name was Friend but which he changed to his mother’s maiden name; she, too, was named Nancy Hanks. He was ten years older than Abraham, shared the cabin loft with him, and became his constant companion.

About forty families, most of them migrants from Kentucky, lived within five miles of the Lincolns around a town they called Little Pigeon Creek. In the autumn of 1818, the small community was stricken with “milk sickness,” an epidemic that claimed thousands of lives in the region. Thomas Sparrow caught the illness first, and then Elizabeth, and finally Nancy, who tended them before their deaths. She died on October 5. Nine-year-old Abraham helped his father build the plain wooden coffins. “O Lord, O Lord,” recalled Dennis Hanks, “I’ll never forget the misery in that little green log cabin when Nancy died!” In his old age, he told an interviewer about Lincoln, “He never got over the miserable way his mother died. I reckon she didn’t have no sort of care—poor Nancy!” Abraham, the most literate member of his family, wrote a letter to Pastor Elkins requesting that he travel to perform a funeral service, and he came some months later, perhaps even a year later, preaching at her grave.

![]()

Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln

![]()

Eleven-year-old Sarah was now in charge of the household duties, including care of her brother. “He tried to interest little Sairy in learning to read, but she never took to it,” recalled Dennis Hanks. “Sairy was a little gal, only eleven, and she’d get so lonesome, missing her mother, she’d set by the fire and cry. . . . Tom, he moped ’round.” Thomas left twice for long periods of time, abandoning the children to forage for food in the wilderness. The first time he went to sell pork down the Ohio River; the second to bring back a new wife. He had proposed to Sarah Bush Johnston years before in Kentucky, but she rejected him for the Hardin County jailer, a better catch. Now a widow, she accepted him, a strategic domestic alliance, and in another trek from Kentucky he brought her and her three children to the dirt floor cabin in Little Pigeon Creek. She discovered Abraham and Sarah “wild—ragged and dirty,” and immediately washed them so they “looked more human.” One chronicler who spoke with eyewitnesses recalled, “Mr. L does not appear to have cared for home after the death of his mother.” But his stepmother brought order and affection to his life. “Abe was the best boy I ever saw or ever expect to see,” she said. And he described her as his “kind, tender, loving mother,” to whom he was “indebted more than all the world for his kindness.”

Sarah Bush Lincoln brought civility and domesticity to the rough existence of Thomas Lincoln. She filled a wagon for her new life with her belongings—pots and pans, pewter dishes, pillows, and blankets. Then she made him put in a wooden floor and build beds and chairs. She made everyone wash before dinner. And, according to Dennis Hanks, she made her husband join a church.

Thomas helped construct the new church in the village, the Little Pigeon Creek Baptist Church, affiliated with the United Baptist Association, bridging the Regular Baptists and the Separate Baptists, which refused to have any written articles of faith and to which Thomas adhered. He would not join the Little Pigeon Creek Church, the only one in the town, for seven years, until the theological schism was resolved—and his new wife insisted.

The pastor of the church, Thomas Downs, was the brother of William Downs, also undoubtedly sharing his antislavery creed. Thomas Lincoln became a church trustee and young Abe served as sexton. Two other preachers at the Little Pigeon Creek Church were “Emancipationists,” Alexander Devin and Charles Polke, who had been members of the Indiana constitutional convention that wrote a section going beyond the prohibition on slavery in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 to ban “the indenture of any negro or mulatto” made in another state, effectively preventing slave states from extending their reach over black freemen into Indiana. Thus the figures of moral authority of the tiny rural community where Lincoln experienced his earliest formative shaping were antislavery.

Sarah Bush Lincoln could not help noticing that “Abe read all the books he could lay his hands on . . . he read diligently . . . he didn’t like physical labor—was diligent for knowledge—wished to know and if pains and labor would get it he was sure to get it.” John Hanks, Dennis’s brother, who came to live with the Lincolns in 1823, called him “a constant and voracious reader.” He was sent to school for less than a year, the most extended period of formal education he ever received, a “blab” school where pupils were made to recite lessons in unison. “There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education,” Lincoln wrote in his 1858 autobiography. But Dennis Hanks pointed to the memory of Nancy Lincoln as the initial spark for Abe’s education. “I reckon it was thinking of Nancy and things she’d done said to him that started Abe to studying that next winter. He could read and write. Me and Nancy’d learned him that much, and he’d gone to school a spell; but it was nine miles there and back, and a poor make-out for a school, anyhow. Tom said it was a waste of time, and I reckon he was right. But Nancy kept urging Abe to study. ‘Abe,’ she’d say, ‘you learn all you can, and be some account,’ and she’d tell him stories about George Washington, and say that Abe had just as good Virginny blood in him as Washington. Maybe she stretched things some, but it done Abe good.” But it was his stepmother who was the guardian of his education. “She didn’t have no education herself, but she knowed what learning could do for folks.” Unlike her husband, she valued ambition and invested it in her stepson.

Lincoln read whatever books he could find and whenever he could. He read Weems’s Life of George Washington, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, and Aesop’s Fables. He studied Noah Webster’s American Spelling Book, among other standard schoolbooks. He read Lindley Murray’s English Reader, containing an antislavery poem by William Cowper, “I would not have a slave to till my ground,/to carry me, to fan me while I sleep,/And tremble when I wake, for all the wealth/that sinews bought and sold have ever earn’d./I had much rather be myself the slave,/And wear the bonds, than fasten them on him.”

“I induced my husband to permit Abe to read and study at home, as well as at school,” recalled Sarah Bush Lincoln. “At first he was not easily reconciled to it, but finally he too seemed willing to encourage him to a certain extent. Abe was a dutiful son to me always, and we took particular care when he was reading not to disturb him—would let him read on and on till he quit of his own accord.”

Most people thought of reading as indolence. “Lincoln was lazy—a very lazy man,” said Dennis Hanks. “He was always reading—scribbling—writing—ciphering—writing poetry.” “Abe was not energetic except in one thing—he was active and persistent in learning—read everything he could,” said his stepsister Matilda Johnston Moore. John Romine, a neighbor, who hired him as a day laborer, said, “Abe was awful lazy: he worked for me—was always reading and thinking—used to get mad at him.” Thomas Lincoln believed his son’s reading was willful shirking and he punished him for it. “He was a constant and I may say stubborn reader, his father having sometimes to slash him for neglecting his work by reading,” recalled Dennis Hanks.

Thomas Lincoln was not naturally an angry or harsh man. “He was a man who took the world easy—did not possess much ...