![]()

1 The ‘Night Entertainment of Han Xizai’

BREAKING TEXTUAL ENCLOSURES

A passage from the Xuanhe huapu, the painting collection catalogue of the Song dynasty Emperor Huizong (r. 1101–26), recounts the creation of Gu Hongzhong’s tenth-century masterpiece, the Night Entertainment of Han Xizai (illus. 13):

Gu Hongzhong was from south China and served the Southern Tang emperor Li Yu [r. 961–75] as a court painter. A skilled artist, he was particularly good at portraying figures. At that time Han Xizai, who held the office of Internal Secretary, was illustrious and all his acquaintances were from the hereditary nobility. Han was obsessed with beautiful singing-girls and at night held endless drinking parties. He imposed no restraint on his guests, who mixed with his ladies, shouting in wild excitement. His reputation for indulgence spread both inside and outside the court.

Li Yu, the Southern Tang emperor, valued Han Xizai’s talent as a statesman and overlooked the matter, but he regretted not being able to see Han’s famous parties with his own eyes. So he sent his court painter, Gu Hongzhong, as a detective to Han’s night entertainments, instructing him to recreate everything he saw there based on his memory. The painting, the Night Entertainment of Han Xizai, was then made and presented to the throne.29

Written some nine hundred years ago, this passage and other early textual records of Gu Hongzhong’s work have become its ‘primary references’ and have set the basic tone of the scholarly inquiry into the painting. Almost all writers on the Night Entertainment of Han Xizai begin from such records and ponder the motivation behind the painting’s creation. Later writers always have the privilege to consult yet more ‘references’ and ‘sources’, which increased steadily both in quantity and form. Gradually, not only was the painting recorded in catalogues and other types of text, it also began to carry its own texts: colophons. Modern printing technology has further allowed people to ‘edit’ the long handscroll to suit a book format; the painting (or more precisely, its edited reproductions) can thus conveniently accompany and ‘illustrate’ a scholarly argument. These historical records, colophons and modern writings constitute what I call ‘textual enclosures’, which simultaneously yield and block off an entrance to the painting itself. They serve as a bridge to the painting because they contain useful information and judgements; but we often benefit from this information and these judgements at the expense of a fresh look at the original work. Of course, none of these texts automatically represents the historical truth; even the record in the Xuanhe catalogue appeared no less than 150 years after Gu Hongzhong’s time. Can we rely on this and other texts? Can we penetrate the layers of textual shells to gain a direct look at the painting? In other words, can we reinstall the painting’s status as the subject of an original visual analysis? We cannot avoid these questions because they determine our interpretative strategies. The only way to answer them, I believe, is to define the historicity of the various ‘textual enclosures’ and their relationship with the painting.

Returning to the record in the Xuanhe catalogue, we find that the writer of the passage, who was very likely Emperor Huizong himself,30 paid more attention to the historical anecdote than to the painting, about which he said not a single word. The two main characters in his story are Li Yu, the patron, and Han Xizai, the subject of the painting; the painter is mentioned only as an invisible middle-man between the curious ruler and the libertine minister. Indeed, compared to the humble court artist, these two men are illustrious figures; Li Yu in particular is one of the most romantic rulers and celebrated artists in Chinese history. It was in his small court that the twilight of the great Tang empire gradually faded into a private refinement of the most exquisite elegance. Li Yu, better known as Li Houzhu or Li the Last Ruler, was himself a famous poet, and he was also renowned as a leading connoisseur of music, dance, calligraphy and painting. It is said that on his request his favourite concubine danced on a sculptured and gilded lotus-flower, moving along with the music performed by the emperor himself. Such a ruler became a natural focus of fascination and criticism. His life, which began in a fantastically luxurious court and ended in a nightmarish prison,31 evokes both sympathy and disgust. His beautifully composed sentimental verses, especially those written after his capture by the Song army, were widely read throughout later Chinese history; but as a political figure, he is constantly accused (especially on public occasions) of being an incapable ruler, one whose delicate art foreshadowed the fall of his dynasty.

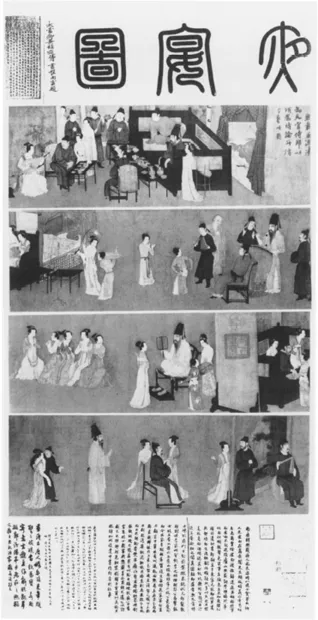

13 After Gu Hongzhong, Night Entertainment of Han Xizai, (?)12th-century copy of a 10th-century work, handscroll, ink and colour on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing. | |

Li Yu and his court had become a subject of historical reconstruction and fictional imagination by the early Song. The sweeping destruction of the Southern Tang archives and art collection must have encouraged this tendency. It is said that before surrendering his capital to the invading Song army, Li Yu entrusted Madame Huang, a court lady who was in charge of his art treasures, to destroy ‘the tens of thousands of pictures and calligraphic works in the palace, including writings by ancient masters such as Zhong You and Wang Xizhi’.32 Ma Ling, the Song author who recorded this event in his Southern Tang History, opened his book with a preface (dated 1105) identifying the sources of his records. According to him, on the Southern Tang’s fall, its historians gathered the government documents together, burned them to ashes and then committed suicide. As a consequence, the founder of the Song had to order Xu Xuan and Tang Yue, two high officials who had served in the Southern Tang court, to ‘recall and write down what they had heard’ about the perished dynasty. When Ma Ling’s grandfather began to compile a Southern Tang history, he also had to ‘interview officials and commoners who could say anything about this bygone dynasty’.33 This tradition was followed by other Song rulers and writers. The various versions of Southern Tang history thus largely depended on memory and storytelling.

These writings fall into two general categories. Those following the tradition of zhengshi (‘formal’ or ‘standard’ history) recorded and evaluated the most important public figures and events; those following the tradition of yeshi (‘informal’ or ‘unofficial’ history) collected colourful anecdotes, often about private affairs of the social elite. Han Xizai, the subject of Gu Hongzhong’s depiction, held prominent offices under all the three Southern Tang rulers. Not coincidentally, he appeared in both types of writing with very different images. Authors of several zhengshi presented him as a leading statesman in the Southern Tang court. Although his unconventional lifestyle was sometimes noted, he was admired for his political foresight, his literary talent, and his outspokenness. Rarely, if at all, did these authors offer detailed descriptions of Han’s private life.34 Such descriptions are trademarks of yeshi writings that, though often attributed to certain ‘eyewitnesses’, were likely compiled by authors during the century after the Southern Tang’s fall.35 If Han Xizai’s image remained relatively static in the official history tradition, it was highly metamorphic in these unofficial histories, in which his eccentricity was continuously elaborated and exaggerated. Interestingly, only these ‘informal’ historical writings recorded a painting, sometimes called the ‘Night Entertainment’ (Yeyan tu). Attributed either to Gu Hongzhong, to Gu and other court painters, or to certain ‘later people’, it was freely associated with various events and given different rhetorical roles.

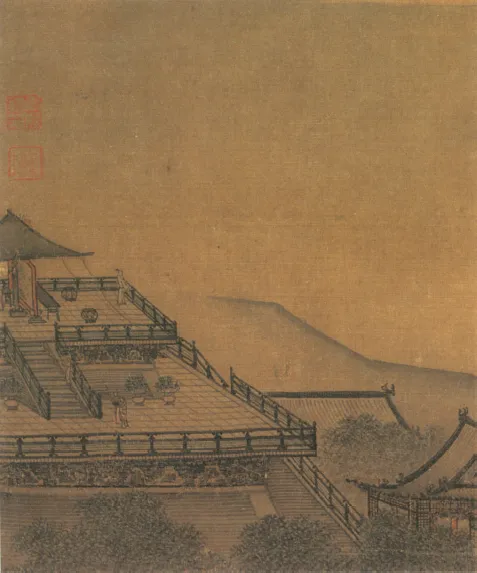

14 Passing a Summer in the Shade of a Locust Tree, (?)early Ming, album leaf, ink and colour on silk. Palace Museum, Beijing.

15 Attributed to Ma Yuan (fl. 1190–1225), Viewing Clouds from a Palace Terrace, 13th century, album leaf, ink, colour and gold on silk. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

16 Detail of illus. 15.

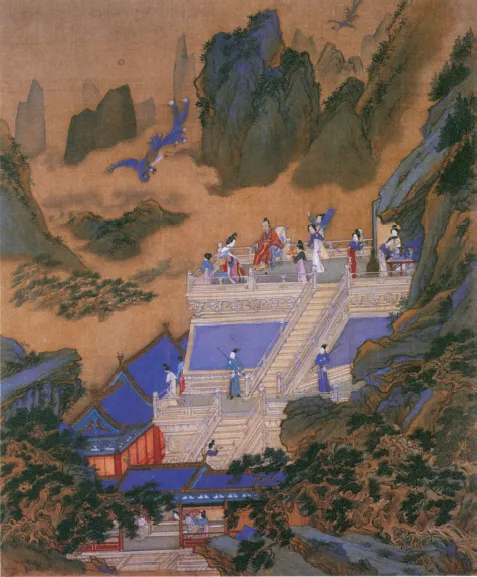

17 Qiu Ying (1502–51), ‘Playing the Flute to Attract Phoenixes’, a leaf from A Painted Album of Figures and Stories, 16th century, ink and colour on paper. Palace Museum, Beijing.

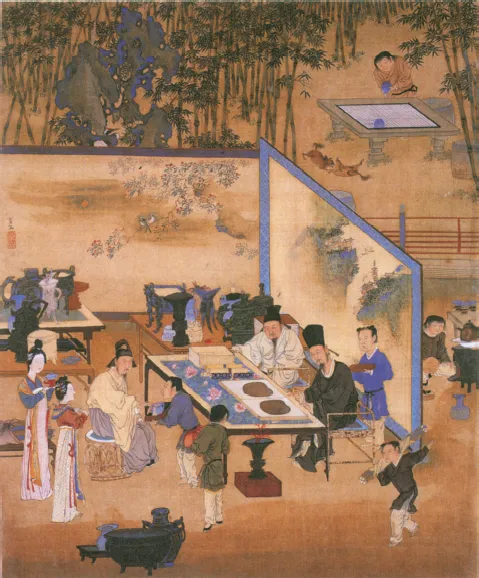

18 Qiu Ying, ‘Ranking Ancient Works in a Bamboo Court’, a leaf from A Painted Album of Figures and Stories, 16th century, ink and colour on paper. Palace Museum, Beijing.

19 scenes from Gu Hongzhong’s Night Entertainment of Han Xizai (illus. 13). The sequence runs 21, 19, 22, 20.

20 scenes from Gu Hongzhong’s Night Entertainment of Han Xizai (illus. 13). The sequence runs 21, 19, 22, 20.

21 scenes from Gu Hongzhong’s Night Entertainment of Han Xizai (illus. 13).

22 scenes from Gu Hongzhong’s Night Entertainment of Han Xizai (illus. 13).

23 A detail of illus. 40.

(1) Zhao Lingji (1061–1134), Records of the Miscellanies: ‘Han Xizai [was from north China but] held the post of Prime Minister in the land south of the Yangzi River. After Li Yu ascended the throne, this new ruler did not trust the northerners in his court, some of whom were found dead of poisoning. Afraid of disaster, Xizai abandoned himself to sensual pleasure, paying no respect to social norms and regulations. He exhausted his family fortune to purchase several hundred singing-girls and female performers. He found joy in dissipation, and there was nothing he did not dare to do [for pleasure]. His monthly salary was not even enough to support his household. He then disguised himself as a blind man, wearing old clothes and broken shoes while playing a stringed instrument. His student Shu Ya guided him around while beating out the rhythm on a clapper-board. They travelled along his ladies’ chambers, begging for money to buy their daily food. Later people thus painted the “Night Entertainment” picture to ridicule him.’36

(2) Anonymous (11th-12th centuries?), Chatting on a Fishing Jetty: ‘Han Xizai’s monthly salary was divided by his ladies as soon as it arrived. When there was no money left to buy food for the household, he disguised himself as a blind man, dressed in shabby clothes and shoes and played a single-string lute. Shu Ya guided him around while playing a clapper. Together they travelled along his ladies’ chamber begging for money to buy their daily food. At the time, Chen Zhiyong also had no money at all but kept several dozens of women in his household. Chen, who was a good friend of Han, also failed to be promoted [because of his bad reputation]. People thus wrote a poem to make fun of them: “Mr Chen’s colourful shirt resembles that of an opera singer; Master Han’s official payment dissolves like the sound of a jingling bell.,, Li Yu the Last Ruler often attended Han Xizai’s private banquets. He ordered the Painter-in-Attendance Gu Hongzhong and other court artists to depict [these banquets] and to present their painting(s) to him.’37

(3) Tao Yue (11th-12th centuries), Supplements to the Five Dynasties History: ‘Han Xizai pursued his official career south of the Y...