![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The social web and searchable talk

The above microposts1 were published online with a microblogging service; that is, an online platform for posting small messages to the internet in chronological sequence. The first post describes a mundane event in daily life. The hashtag #Fail aligns this personal expression with other potential instances of quotidian failure sharing the same tag. Hashtags are an emergent convention for labelling the topic of a micropost and a form of metadata incorporated into posts. The second post is a more public declaration of support for victims of an earthquake in the New Zealand city of Christchurch. It is similar to many other microposts produced during natural disasters and crises throughout the world. Like the first post, the hashtags #Christchurch and #eqnz, in this instance, seek parallel voices. The two posts differ greatly in the kind of connection they construe with a putative audience. Yet both actively invite connection with that audience by incorporating a hashtag to label the meanings they express. This kind of discourse tagging is the beginning of searchable talk, a change in social relations whereby we mark our discourse so that it can be found by others, in effect so that we can bond around particular values (Zappavigna 2011b).

Here we have the potential for users to commune within the aggregated gaze made possible with digital media, which I shall call ambient affiliation in this book. In other words, virtual groupings afforded by features of electronic text, such as metadata, create alignments between people who have not necessarily directly interacted online. Indeed these users may never be able to grasp the extent of the emergent complexity in which they are involved due to the fast paced, organic quality of the connections generated. The social relationships made possible will emerge over time, generated and influenced by unfolding linguistic patterns.

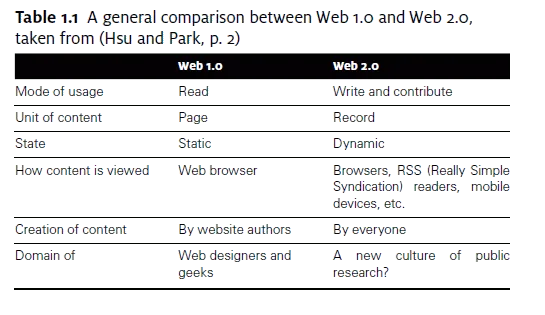

The social web, or Web 2.0, are popularized terms used to signal a shift toward the internet as an interpersonal resource rather than solely an informational network. In other words, the social web is about using the internet to enact relationships rather than simply share information, although the two functions are clearly interconnected. Table 1.1 gives an overview of the ways in which the social web is said to differ from the first incarnation of the internet. At its centre is ‘user-generated content’; that is, self-publication by users2 of multimedia content such as blogs (websites displaying entries in reverse chronological order), vlogs (video blogs such as those posted regularly by millions of users on YouTube) and microblogs (streams of small character-constrained posts). This book will deal primarily with microblogging, sometimes seen as a cousin of more lengthy blogging, although likely quite a different meaning-making resource entirely.

The advent of social media, technology that aims to support ambient interpersonal connection, has placed new and interesting semiotic pressure on language. This book is concerned with the interpersonal dimension of making meaning using this new media. Social media is an umbrella term generally applied to web-based services that facilitate some form of social interaction or ‘networking’. This includes websites where the design-principle behind the service is explicitly about allowing users to create and develop online relationships with ‘friends’ or ‘followers’. The term also encompasses platforms where the focus is on generating and sharing content, but in a mode that allows comment and, potentially, collaboration.

Because of the rapid development of social media technologies and their constant change, they can be somewhat of a ‘moving target’ for scholars (Hogan and Quan-Haase 2010).

While I will comment on social media in general, my analysis will focus on patterns of meaning in microblogging. The method adopted in this book for exploring this patterning combines quantitative analysis of a large 100 million word corpus of microposts, HERMES, with a qualitative social semiotic approach to discourse analysis. These posts were taken from the microblogging service Twitter. Developed in 2006, Twitter allows users to post messages of 140 characters or less to the general internet or to a set of users who subscribe to a user’s message ‘stream’,3 known collectively as followers. These microposts are referred to as tweets and are presented to the user in reverse chronological order as an unfolding stream of content. This content is public and searchable unless the user actively makes his or her account private. Tweets may be accessed, sent and received via a variety of methods such as the web, email, SMS (Short Message Service) and third-party clients, often running on mobile devices. A tweet may also incorporate links to micromedia, small-scale multimedia and shortened aliases of longer hyperlinks (tiny URLs) intended to conserve characters within the constrained textual environment. In addition, Twitter collects supplementary metadata about a tweet, such as the time it was generated, the ID of the user to which the tweet was directed (if applicable) and information about the user’s account, including the number of followers and the number of tweets the user has posted.

An example of a tweet is the following, which, as we will see in the third chapter, contains one of the most common patterns in microblogging, namely, a user thanking a follower for promoting him or her in the community:

This post thanks User1 for the mention as part of Follow Friday, a collective practice where users are encouraged to endorse noteworthy tweeters. Tweets also contain metadata for managing interaction with others, for instance, @ indicating address (or reference) and # labelling topic. I will explore these features in more detail later in this book. While most of the metadata collected by Twitter is not presented directly to the general user, a notable exception is hashtags. These tags, a kind of in-text tagging visible within the body of a tweet, arose out of community use and were later incorporated into Twitter’s search interface.

From a simplified technical perspective, Twitter consists of a farm of large databases that store the tweets that users have posted. The volume of this database of natural language is extremely large, with many millions of tweets being posted each day. Since its inception, Twitter has seen an extremely large increase in its user base. Prior to 2008–09 the service was mainly used within the technology scene in the United States, after which it became more mainstream, with users posting status updates on everything from the most innocuous details of their personal lives to serious political opinion and reporting (Marwick 2010). Twitter’s technical architecture has had to cope with a very high volume of traffic:

From the viewpoint of users, Twitter consists of an interface that allows people to post new tweets, configure various settings, such as privacy, manage their list of followers and search historical tweets. Users may also interact with the service via a third-party application that presents the feeds of microposts in different ways, in some cases in novel visual forms. The extremely large volume of naturally occurring language is of great interest, as data, to linguists.

An important property of the social web is how it responds to time. Social media content is most often chronologically displayed. Indeed, many commentators describe the emergence of a ‘real-time web’4; that is, a paradigm whereby web content is streamed to users via syndication. Tools, such as a feed reader, are used to aggregate many web feeds into a single view, meaning that users do not have to visit sources individually for current information. This type of convergent, real-time web experience combines with the social web to produce a semiotic world in which users have almost immediate access to what is being said in their social networks at any given moment. Users are able to subscribe to feeds of their associates’ status updates and multimedia content (e.g. photos and video). Often these updates are shared via a mobile device at the time an event occurs or an observation is made.

An example of the real-time web in action might be the reactions to a major public event, such as the 2008 US presidential election (see Chapter 9), that are shared via microblogging. Even local, less significant events, such as weather, can trigger communal response. For instance, during a recent hailstorm in Sydney, a proliferation of comments about hail and photographs of hail rapidly appeared in my online social network via status updating on Facebook and Twitter. Many other kinds of events generate widespread social media response, including natural disasters, such as the 2008 Sichuan earthquakes (Li and Rao 2010), and celebrity deaths, a notable example being the collective outpouring of grief seen on Twitter after the death of Michael Jackson in 2009 (Sanderson and Hope Cheong 2010).

An important function of social media is sharing experience of the everyday within this real-time paradigm. In microblogging this often involves bonding around collective complaint about life’s little daily irritations (see Chapter 8). While social media can be used ‘like Momus windows of Greek mythology, revealing one’s innermost thoughts for all to see’ (van Manen 2010), most users are conscious of not overexposing their followers to banalities, a practice known as over-sharing, or ‘attention whoring’ (Marwick 2010).

Perhaps the most commonly used form of social media is the social networking service (SNS). This technology, used by millions of people worldwide, generates a very large volume of multimedia text. At the time of writing in 2010, Facebook had over 500 million users, each with an average of 130 Facebook ‘friends’ (Facebook 2010), and Twitter users were generating 65 million Tweets a day (Schonfeld 2010). SNSs are services with which users create an online profile about themselves with the goal of connecting with other people and being ‘findable’. Boyd and Heer (2006) suggest the role of online social network profiles in identity performance as an ‘ongoing conversation in multiple modalities’. Indeed, interactions via social media are usually likened to some form conversation. Depending on the kind of relationship being construed, the ‘dialogue’ may be fairly limited, often involving two main avenues: making initial contact with a user and then maintaining occasional contact at important dates, such as birthdays (2010).

Most SNSs have in common a number of basic functions: profile creation, the ability to generate a list of affiliated users, privacy customization, and a mechanism for viewing the activities of affiliated users. These affiliated users are often referred to as ‘friends’ (e.g. Facebook friends) or ‘followers’ (e.g. Twitter followers). Boyd (2010, p. 39) categorizes SNSs as a genre of ‘networked publics’ involving an ‘imagined collective’ arising from particular permutations of users, their practices and the affordances of technology. Four affordances Boyd suggests are of particular significance:

As we will see in the next chapter, these properties, particularly persistence and searchability, mean that SNSs afford an opportunity to collect and analyse many different aspects of online discourse. The large volume of data made publically available by these services offers a fascinating window on social life, though it also raises a range of ethical concerns about how this data is used (Parrish 2010).

Interpersonal search

Through the social web, talk is ‘searchable’ in a way and to an extent that has never been seen in history. The advent of social media means that the function of online talk has become increasingly focused on negotiating and maintaining relationships. From a semiotic perspective the searchability affords new forms of sociality. We can now search to see what people are saying about something at a given moment, not just to find information. This makes possible what I will refer to as interpersonal search; that is, the ability to use technology to find people so that you can bond around shared values (or clash over discordant ones!). The searchability is particularly useful for linguists collecting particular kinds of discourse, for example, online chatter about a particular topic or language occurring in a particular geographical region. The conversation-like interactions possible with social media can be tracked in ways not readily achievable with face-to-face interaction in the real world, where it would be invasive to monitor a person’s private interactions.

In popular terms, it is becoming increasingly useful to search the ‘hive mind’: the stream of online conversation occurring across semiotic modes (e.g. blogs, online chat and social networking sites). The kind of real-time discourse search that Twitter affords has been described as a rival to a Google search, with commentators claiming that searching Twitter may soon be one of the most effective ways to gather useful information (Rocketboom 2009). Microblogging streams offer a way of finding out about dominant trends in what people are saying. For instance, consider the following anecdote by Boyd (2009), who applies an ethnographic perspective to her social media research:

This notion of interpersonal search is a linguistic perspective on the concept of social search used within information science. The term ‘social search’ refers to a mode of searching that leverages a user’s social networks, for example, by asking a question on a social networking site. This mode of search is deemed complementary to an informational search with a search engine. Evans and Chi (2008) provide the following definition:

Meredith Ringel and colleagues surveyed users of social networking services, such as Twitter and Facebook, about the nature and motivation of the questions they asked using these media. Recommendation and opinion questions were the most frequent; a recommendation question was defined as asking ‘for a rating of a specific item’ and an opinion question as ‘open-ended request for suggestions’ (2010, p. 1742). The most common motivation expressed by respondents for engaging in this form of social search was a higher perceived level of trust in their friends to provide replies to questions deemed too subjective to be effectively answered by a search engine. Indeed, one study found differences in the kinds of queries issued to the Twitter search engine compared with those issued to a web search engine and that ‘Twitter results included more social content and events, while Web results contained more facts and navigation’ (Teevan et al. 2011, p. 44). These studies suggest that interpersonal meaning is at the heart of social search. Social bonds have becoming increasingly important in the way information is located and consumed with the internet. The significance of interpersonal search forms part of an explanation for the proliferation of social recommendation sites, social bookmarking, crowdsourcing5 and related practices that make use of the social opinions extractable from online networks.

Approaches to online social networks

Social media affords a lens on types of social interaction previously not easily viewed. The streams of online social contact produced by users leave permanent trace...