![]()

CHAPTER 1

Settlers, Soldiers, Indians, and Officials

The Chaos of French Rule

| Capon vive longtemps. | The coward lives a long time.

—from Lafcadio Hearn, Gombo Zhèbes: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs |

The colonization of the Americas was the earliest stage of the internationalization of the world. New cultures were formed through the encounter of peoples from Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Varying social and cultural patterns emerged, determined to a great extent by the economy, labor demands and necessary skills, the physical environment, the priorities of the colonizing power, the racial, national, gender, and age structure of the population, and the level of peace, security, and stability prevailing in the various colonies.1 Louisiana, first colonized by France, was a strategic colony, where military considerations outweighed economic concerns. French control was extremely fragile. French Louisiana was a chaotic world where the cultural materials brought by Africans often turned out to be the most adaptive.

The founding of French Louisiana must be understood within the context of the French empire in North America. France’s primary concern was to prevent England from gaining control of the mouth of the Mississippi River.2 By colonizing the Mississippi Valley, France intended to outflank and surround the British mainland colonies along the Atlantic coast. With control of Canada, the St. Lawrence waterway, and the Mississippi Valley, France could dominate the continent. At the end of the seventeenth century, France, Britain, and Spain rushed to claim the strategic Mississippi River Valley.3 France explored down the Mississippi River from her Canadian settlements and staked her claim, establishing a beachhead at Biloxi, in 1699, on what is now the Mississippi coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

France was ill equipped to begin this ambitious undertaking. The country was exhausted by the wars of Louis XIV. The War of the Spanish Succession began in 1702, shortly after Louisiana was founded, and raged for more than a decade. France’s population had been drained and reduced to dire poverty and its treasury bankrupted by protracted warfare. An ambitious continental power with no natural boundaries to protect its frontiers, France was reluctant to allow the departure of its “useful” population. This vast colony, which included the entire Mississippi Valley, was therefore thinly populated by whites, many of whom were the rejects of French society—the defiant ones, both civilians and soldiers, who challenged and threatened the brutal and exploitative social structure of prerevolutionary France. Others were Canadian courreurs du bois, fur traders who lived in Indian villages and often took Indian women for wives. Many French settlements of lower Louisiana began in Indian villages.4

The first census of Biloxi, dating from December, 1699, lists 5 officers, at least 2 of whom were Canadians, 5 petty officers, 4 sailors, 19 Canadians, 13 pirates from the Caribbean, 10 laborers, 6 cabin boys, and 20 soldiers. With this motley crew, France established her claim to the entire Mississippi Valley and the coast of the Gulf of Mexico between the Spanish colonies of Florida and New Spain (Mexico). The colony developed slowly. According to a census taken on August 1, 1706, Louisiana had a total of 85 French and Canadian inhabitants, 48 of whom were in the pay of the king. On August 12, 1708, there were, in all of Louisiana, 278 persons in French settlements, including 80 Indian slaves of both sexes, 14 major officers, 76 soldiers, including 4 army officers, 13 sailors, including 4 marine officers, 3 Canadians, one of whom served as interpreter for the Chickasaw language, 1 valet, 3 priests, 6 workers, and 6 cabin boys (mousses) who had been brought in to learn Indian languages, as well as to serve on sea and land. The garrison totaled 120 men. Aside from Indian slaves and military personnel, there were only 24 male settlers, 28 women, and 25 children, none of whom had been assigned land. The Canadian courreurs du bois were the bestadapted colonizers, but they were not considered legitimate settlers. The 1708 census mentions “over 60 wandering Canadians who are in the Indian villages situated along the Mississippi River without the permission of any governor and who destroy by their bad and libertine conduct with the Indian women all that the missionaries and others teach the savages about the divine mysteries of the Christian Religion.”5

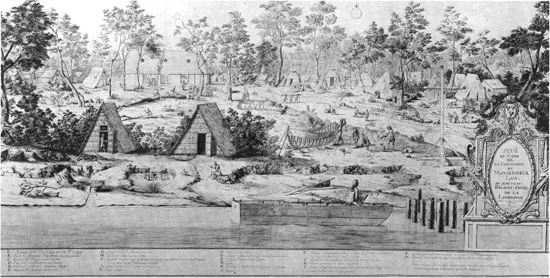

View of the camp of John Law at Biloxi. The original print dates from December, 1720.

Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection, Museum/Research Center, Acc. No. 1974.25.10.168.

When Antoine Crozat turned Louisiana over to John Law’s Company of the West in 1717, the French population, including men, women, and children, totaled only about 400.6 The Company of the West was a private company that issued and sold shares. It was granted a monopoly of Louisiana’s trade for twenty-five years and of the Canadian beaver trade in perpetuity, and it was given ownership of lands and mines as well as the right to build fortifications and to nominate company directors and colonial officials. The king assumed the responsibility for manning and maintaining the forts and garrisons and for furnishing Indian presents. The Company of the West was expanded to include the Company of Senegal in December, 1718, the Company of China and the East Indian Company in 1719, and the Company of St. Domingue and the Company of Guinea in September, 1720. This conglomerate was then renamed the Company of the Indies.7

The advent of John Law and the Company of the West opened the way for the true colonization of Louisiana and its transformation from simply a weak military garrison. Permanent settlers were brought from France in significant numbers. But it was hard to find voluntary colonists in France, and there was, moreover, a great reluctance to allow useful subjects to leave the country. Louis XIV had resisted the notion of populating his colonies by forcing indigent subjects to go to America. But these qualms died with him, and when the Company of the Indies began to colonize Louisiana, a new philosophy prevailed. The French colonization of Louisiana became to a great extent a penal colonization. During 1717 and 1718, the sentences of prisoners who had been condemned to the galleys were commuted, and these prisoners were sent to Louisiana to work for three years. Thereafter, they were to be given part of the land they had cleared and cultivated. The prisoners were brought to the ports under heavy guard and chained aboard the ships. Also during this period, soldiers who had deserted, vagabonds, and persons without means were placed upon lists of those to be deported to Louisiana. Some had been arrested for acts of violence, murders, debauchery, and drunkenness, but they were mostly beggars and vagabonds from Paris and all the provinces of France. By 1719, deportation to Louisiana had become a convenient way to get rid of troublesome neighbors or family members. Some families asked for deportation of incorrigible sons, daughters, and nephews. Persons from all social milieux were denounced for their conduct, and police inquiries were held. Comments found in police files included “Here is a true subject for Louisiana” and “A very bad subject who deserves … to be among those who are destined for the new colonies.”8

During 1719, 416 men accompanied by 30 women and children were deported from France to Louisiana. During the same year, 134 more women were deported. Many other women had escaped while being forced toward the ports. Some of the women had been removed from dungeons. One had been accused of fifteen murders. Most of these women were in their thirties and had been accused of theft, debauchery (sometimes with married men), prostitution, repeated lies, blasphemy, irreligion, and assassination. Some were put on the deportation list at the request of their families. The superior of Salpetrière asked that a number of women be deported because of their rebellion in prison. The sister superior asked to “deliver l’hôpital and the public from a number of seditious women.” By July, 1719, there were more than 220 women on the deportation list.9

A special police force received a head tax for each person apprehended for possible deportation. Members of the force roamed around Paris and the provinces grabbing people for profit, their actions often based upon false accusations. Bloody collisions took place in Paris between these police brigades and the population. Kidnapping occurred; fights between police and potential deportees, as well as full-scale riots, erupted in the streets. There were also riots among prisoners in Paris awaiting deportation to Louisiana. On January 1, 1720, the prison of St. Martin-des-Champs held 107 prisoners destined for Louisiana. Fifty men and women forced the doors, wounded 2 guards, and fled. In order to restore public peace in France, the king, on May 9, 1720, forbade further forced deportations to Louisiana.10

In French Louisiana, usefulness was the overriding virtue for immigrants, transcending race, nation, humanity, and any other consideration. The deportees were not considered utils by officials in Louisiana. A report of June, 1720, referring to colonists sent by the squadron led by de Saujon and by the ship les Deux Frères, commented:

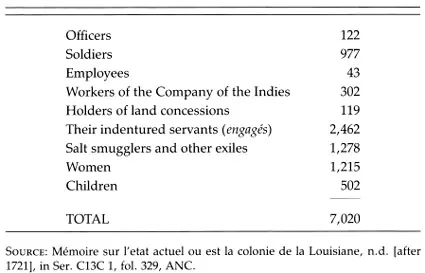

Table 1. French Colonists Sent to Louisiana Between 1717 and 1721

Without wishing to criticize the conduct of the Directors, I dare say that one should not be deluded into believing that it is possible to establish the colony with persons who were incapable of discipline in France, especially since it is noted that a man who was an excellent subject becomes a mediocre subject in America and a mediocre subject becomes very bad. We do not know the reason for this deterioration. Some attribute it to the food which does not have the same substance as in Europe, to a greater dissipation of the mind, or to other causes. Regardless of the reason, the fact is certain. What can one expect from a bunch of vagabonds and wrongdoers in a country where it is harder to repress licentiousness than in Europe?11

Between October 25, 1717, and May, 1721, the Company of the Indies sent 43 ships, which in addition to de Saujon’s squadron, embarked 7,020 colonists. Table 1 gives a breakdown of the colonists.

According to a report written sometime after 1721, about 2,000 whites died during the crossing because of mistreatment by the captains, or they deserted or returned to France. From this information, one could estimate that about 5,420 whites should remain in the colony. However, a census dated January 1, 1726—the first complete census of the entire colony—lists 1,952 French citizens, including Germans, and 276 indentured servants. This drastic drop in population was due largely to an extremely high mortality rate among these white immigrants, both voluntary and forced.12

In 1729, the Natchez Indians and their allies revolted against the French settlers, destroying one-tenth of the white population. The Company of the Indies gave up the colony to the French crown in 1731. Many white settlers left, and practically no new colonists came. The dangerous Indian frontier, poverty, famine, anarchy, and chaos depleted the population and discouraged new immigration. Louisiana was viewed as an expensive, burdensome military outpost, and its colonization with permanent settlers was practically abandoned by France. Diron d’Artaguette, writing from Mobile, described conditions prevailing in 1733: “Our planters and merchants here are dying of hunger, and those at New Orleans are in no better situation. Some are clamoring to return to France; others secretly run away to the Spaniards at Pensacola. The colony is on the verge of being depopulated.”13

In 1738, Edme Gatien de Salmon, commissaire ordonnateur, wrote to the Ministry of Colonies that many settlers had left during the past few years, none at all had entered the colony, the numbers of settlers was decreasing every day, and there had been a heavy mortality among children that year. By about 1740, the white population had been reduced to less than 1,200, including troops as well as settlers, and they were all dispersed. A report from about that time stated: “If it is left in this situation without increasing the population, a catastrophe will happen. It is too extensive to be held on to. … Little by little, the colony is destroying itself.”14

In 1740, Salmon wrote a communique to the colonial ministry, stating that he hoped for some salt smugglers (faux sauniers) on the next vessel of the king, because the colony was being depopulated. These convicts were needed to replace the voyageurs who had been killed during the various defeats suffered by their traders in the Illinois country.15

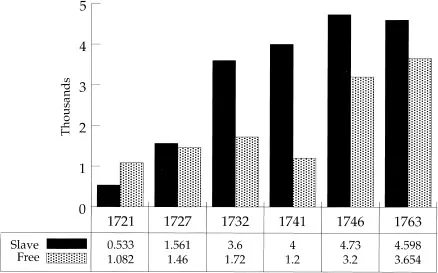

There were no systematic censuses taken by the French authorities in Louisiana after 1731. In 1746, during King George’s War between England and France (1744 to 1748), the white population was estimated to be 3,200, and the black population 4,730.16 Louisiana was thoroughly Africanized during the early years of colonization, and slaves were still a majority in the French settlements when France abandoned the colony to Spain in 1763 (see Figure 1).

Lower Louisiana was not the place to come to establish production of commodities for export. French Louisiana was very poor. Unlike French Canada, where the fishing industry and the beaver trade with the Indians provided a firm economic basis for colonization even though the French population remained small, Louisiana was never a colony of economic exploitation. The furs of lower Louisiana were far inferior to those of Canada, and they often rotted in the humid climate while awaiting a ship. French Louisiana cannot be accurately described as a plantation society. It never really developed a viable, self-sustaining economy. Unlike the French West Indies and the tidewater region of the British continental colonies, Louisiana was not a prosperous slave plantation society producing valuable export staples. It was viewed as the least valuable of France’s colonies, one whose economic development might threaten not only France but also the more important French West Indies.

The ruling elite of French Louisiana was a military-bureaucratic clique whose wealth derived mainly from commerce, often smuggling, and sometimes piracy. Access to trade goods and commercial ties with France were crucial. The Indian fur trade, control of desperately needed supplies, the smuggling of French goods into Spanish Pensacola, Mexico, and Cuba, as well as some piracy, enriched the elite.17 Naval stores and tobacco were exported, but the quality was often poor, and the cost of production, shipping, and transport was prohibitive unless heavily subsidized. Reliance upon the Indian nations to furnish corn quickly wore thin as Indians were encouraged to hunt for pelts and engage in warfare for the benefit of France. French officials often had to feed hungry Indian nations. The first two slave ships from Africa, which arrived in 1719, brought several barrels of rice seed and African slaves who knew how to produce the crop. Rice became the only reliable food crop for local consumption in Louisiana; little was exported. Cotton was grown, but the problem of separating the seed from the lint was never adequately solved. The major agricultural export crops, tobacco and indigo, were normally not competitive in the world market. There were short-lived indigo booms when crops failed in Central America and the French West Indies, floods and insects mercifully spared the Louisiana crop, and a lull in warfare and piracy allowed for shipping. There was little direct trade with France, and trade with the French West Indies was limited during the 1730s and 1740s. During a brief peace between England and France during the early 1750s, small ships brought goods, with a high markup, from France via the islands, taking a return cargo of cypress. But these ships were too small to carry much lumber. Trade and monetary restrictions intended to protect the French West Indies from competition from Louisiana strangled this budding economic development. Additionally, there was a chronic labor shortage. Only one African slave-trade ship arrived in Louisiana after 1731, and the export of slaves from the French islands was prohibited—except for a few the West Indian planters were trying to get rid of—sharply limiting the possibilities of economic growth. The sugar industry also could not develop because of lack of labor and fear of competition with the French islands.18

Figure 1. Slave and Free Population of French Louisiana, 1721–1763

SOURCES: Figures for 1721, 1727, and 1732 calculated from Charles R. Maduell, The Census Tables for the French Colony of Louisiana from 1699 Through 1732 (Baltimore, 1972). Figures for 1741 calculated from Mémoire sur la colonie de la Louisiane, n.d. [ca. 1740], in Ser. C13C 1, fol. 384, ANC. Figures for ...