![]()

1

The Dodgson Family

Family Background

In 1832, at a quiet and somewhat isolated spot in Cheshire, near the village of Daresbury, a child was born who was destined to influence the lives of countless other children for generations to come. He was the first son of Charles and Frances Dodgson and, in the time-honoured family tradition, he was given his father’s first name and also his mother’s maiden name, becoming Charles Lutwidge Dodgson – better known to the world as ‘Lewis Carroll’. (He will simply be called ‘Dodgson’ throughout this book.) He already had two sisters, Frances and Elizabeth, and in the next few years two further sisters, Caroline and Mary, were added to the family. The company of girls was to become a common feature of his life. Eventually, there were eleven children in the Dodgson family – his other siblings being Skeffington, Wilfred, Louisa, Margaret, Henrietta and Edwin.

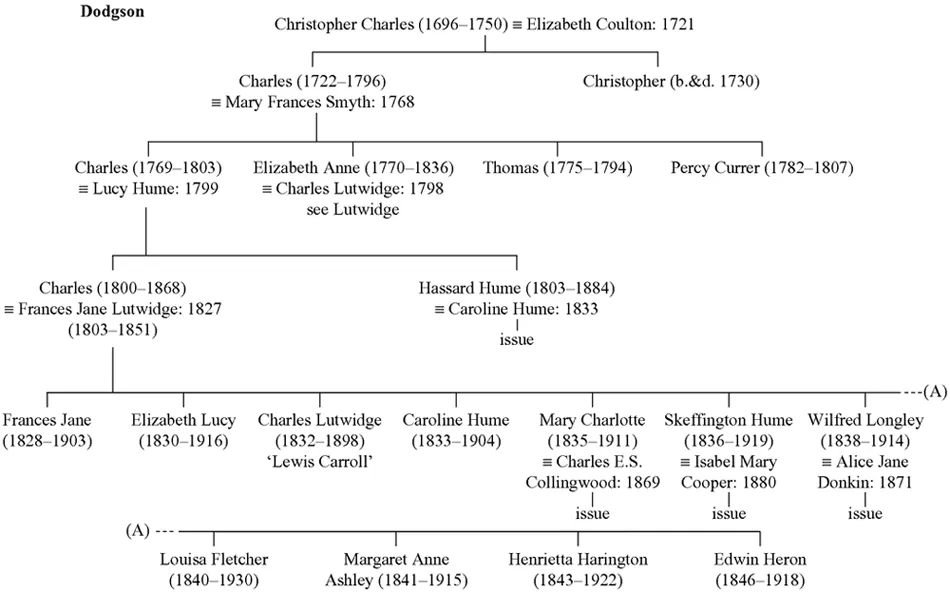

Family Tree 1. The Dodgson Family Tree, constructed by the author

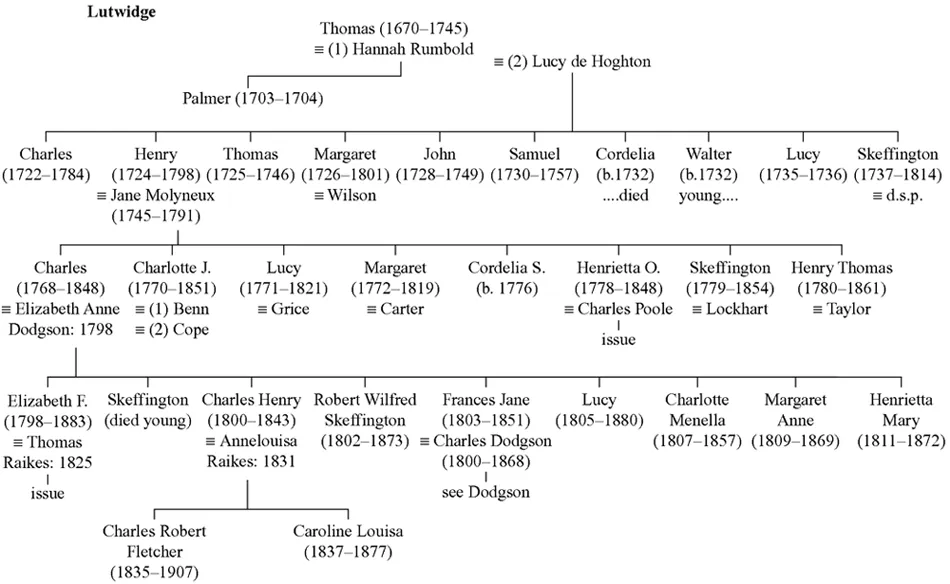

Family Tree 2. The Lutwidge Family Tree, constructed by the authorThe Dodgson family (see Figure 1) did not originate from Daresbury: they had strong North Country connections. Dodgson’s great-great-grandfather, Christopher Dodgson (1696–1750), was a cleric at various parishes in Yorkshire. Christopher Dodgson’s elder son, Charles Dodgson (1722–96), started out as a schoolmaster at Stanwix, Cumberland, but later followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming rector of Elsdon and ultimately becoming bishop of Elphin in 1775. He married Mary Frances Smyth in 1768 and they had four children. Their eldest son, Charles, joined the army and became captain of the 4th Dragoon Guards. He married Lucy Hume in 1799 but tragically was killed in Ireland during an ambush in 1803. The circumstances reveal great bravery. The murderer of Lord Kilwarden offered to give himself up to justice if Captain Dodgson would come alone to take him. Captain Dodgson went to the rendezvous according to the terms of the agreement and was treacherously shot dead from a window. His widow Lucy, pregnant with a son Hassard, already had another son, Charles (1800–68), and it was this Charles who would marry Frances Jane Lutwidge and become Dodgson’s father.

The Lutwidges were landed gentry from Cumberland (see Figure 2). The family seat was Holmrook Hall, purchased in 1759 by Charles Lutwidge (1722–84), the unmarried son of Thomas Lutwidge (1670–1745) of Whitehaven. Thomas married Lucy de Hoghton (1694–1780), daughter of Charles de Hoghton (1643–1710), 4th Baronet, whose own father was Sir Richard de Hoghton, and this family had links back to James I of Scotland.

When Charles Lutwidge died, Holmrook Hall was inherited by his brother, Henry Lutwidge (1724–98). It then passed to Henry’s eldest son, also named Charles Lutwidge (1768–1848), who married Elizabeth Anne Dodgson, daughter of Charles Dodgson (1722–96) and his wife, Mary. Charles Lutwidge settled in Hull and sold Holmrook to his uncle, Skeffington Lutwidge (1737–1814), an admiral in the Royal Navy and one of the first captains to have been appointed by Admiral Horatio Nelson. Charles and Elizabeth had nine children. Their second daughter, Frances Jane Lutwidge (1803–51), married her cousin, Charles Dodgson. These were Dodgson’s parents.

Ultimately, the direct Lutwidge line died out, although a cousin adopted the name by Royal Licence in 1909.1

Dodgson’s Father and Mother

Dodgson’s father was a brilliant mathematician and classical scholar. He went to Westminster School in London at the age of 11 as a King’s Scholar and was made captain (equivalent to head boy) in 1814. He matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1818. He attained the distinction of gaining a double first degree in classics and mathematics in 1821 and was made a Student (with a capital ‘S’) of Christ Church, which came with a small stipend. In other Oxford colleges, this was similar to a fellowship but at Christ Church the dual role of cathedral and college meant that the canons took on the role undertaken by fellows in other colleges. The Studentship could be held for life as long as the conditions of tenure were maintained: the recipient was expected to proceed to holy orders within a few years and to remain celibate. The stipend enabled Charles Dodgson to stay at Christ Church. He took holy orders, being ordained deacon in 1823 and priest in 1824. However, when he fell in love with his cousin, Frances Jane Lutwidge, and married her in 1827, he forfeited his Studentship and was consequentially expected to leave Christ Church. The dean and chapter offered him the Christ Church living of Daresbury, which was not really financially sufficient (being worth about £200 per year), nor intellectually stimulating for a man of his considerable talents. It was probably the only living in the gift of Christ Church available at the time. However, there was little he could do given the circumstances. To supplement his income, he took in paying scholars from the locality, establishing a schoolroom at the parsonage.

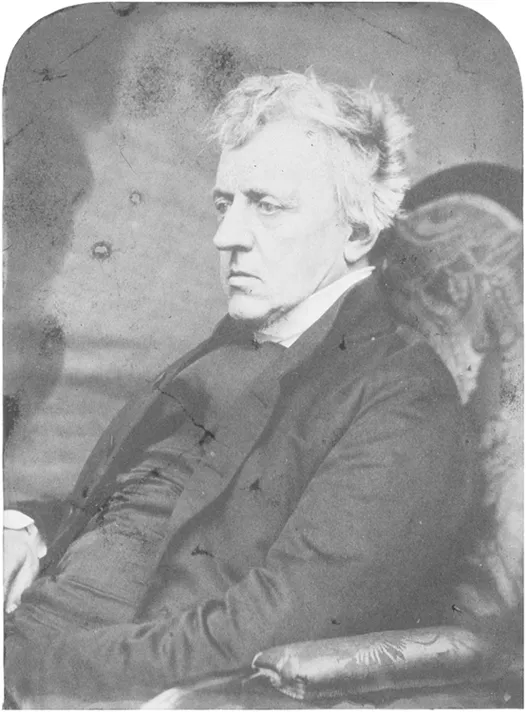

1. Archdeacon Charles Dodgson, from a photograph by CLD, taken in 1859 Dodgson’s relationship with his father was warm yet respectful, and in typical Victorian manner, he was expected to show duty and diligence. He also had the extra responsibility of being the eldest son. There is evidence that Dodgson’s sense of humour came from his father, as the following letter shows. Dodgson senior was away from home at Ripon and sent his 7-year-old son this message:

My dearest Charles,

I am very sorry that I had not time to answer your nice little note before. You cannot think how pleased I was to receive something in your handwriting, and you may depend upon it I will not forget your commission. As soon as I get to Leeds I shall scream out in the middle of the street, Ironmongers, Ironmongers. Six hundred men will rush out of their shops in a moment – fly, fly, in all directions – ring the bells, call the constables, set the Town on fire. I WILL have a file and a screw driver, and a ring, and if they are not brought directly, in forty seconds, I will leave nothing but one small cat alive in the whole Town of Leeds, and I shall only leave that, because I am afraid I shall not have time to kill it. Then what a bawling and a tearing of hair there will be! Pigs and babies, camels and butterflies, rolling in the gutter together – old women rushing up the chimneys and cows after them – ducks hiding themselves in coffee-cups, and fat geese trying to squeeze themselves into pencil cases. At last the Mayor of Leeds will be found in a soup plate covered up with custard, and stuck full of almonds to make him look like a sponge cake that he may escape the dreadful destruction of the Town. Oh! where is his wife? She is safe in her own pincushion with a bit of sticking plaster on the top to hide the hump in her back, and all her dear little children, seventy-eight poor little helpless infants crammed into her mouth, and hiding themselves behind her double teeth. Then comes a man hid in a teapot crying and roaring, ‘Oh, I have dropped my donkey. I put it up my nostril, and it has fallen out of the spout of the teapot into an old woman’s thimble and she will squeeze it to death when she puts her thimble on.’

At last they bring the things which I ordered, and then I spare the Town, and send off in fifty waggons, and under the protection of ten thousand soldiers, a file and a screw driver and a ring as a present to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, from his affectionate Papa.2

Dodgson’s fascination with nonsense and the absurd fits perfectly with the contents of this early letter from his father. Another shared common interest and aptitude was mathematics – both gained high honours in this subject at university.

At an appropriate age, Dodgson received his initial education from his parents. His mother taught him to read and write and gave him lessons in scripture. His father taught him mathematics and later the classical languages of Latin and Greek. The family archive contains evidence of this initial parental education; a notebook dated 1839 indicates that Dodgson, aged 7, studied from various religious texts, including Stories From the Scriptures, The Juvenile Sunday Library and The Picture Testament. His daily reading included such books as Edgeworth’s Early Lessons, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and a six-volume work entitled the Parents’ Cabinet (which included topics on geography, natural history and European history). There is a series of cards produced by his mother to instil moral attitudes, such as Subject 14: ‘If our repentance is sincere, we shall confess and forsake all sins and wickedness’ and Subject 27: ‘True Christians will show love and kindness towards their fellow creatures.’ The cards also included biblical texts that Dodgson was expected to study. Lessons with his mother always began with morning prayers and examples were recorded in the various notebooks that survive, such as this example written in his mother’s hand:

Almighty and everlasting God, who has mercifully preserved me in health, peace, and safety, to the beginning of another day, I thank Thee for this, and all Thy other mercies. I acknowledge and bewail my unworthiness of the least of the many blessings I enjoy, my constant wanderings into sin, and forgetfulness of Thee. …3

This early teaching by his mother remained with Dodgson all his life and was manifest in his personal diaries in a series of prayers and pleas to do better from time to time. Dodgson remained devout and sincere in his Christian upbringing. At an early age he revealed a natural aptitude for academic study, particularly in mathematics. A family anecdote recorded by Dodgson’s first biographer indicated that when he was still a small child he found a copy of Logarithms on his father’s bookshelf and went to him with the plea, ‘Please explain.’ His father said he was far too young to understand, but the boy persisted in his plea: ‘But, please, explain.’ We can assume that the persistence paid off and Dodgson learnt the meaning of logarithms from his father.4

In 1840, Dodgson’s mother made a visit to Hull to see her father, Charles Lutwidge, who had been ill for some time. She wrote home to her brood of children, entrusting the letter to her eldest son:

My dearest Charlie,

I have used you rather ill in not having written to you sooner, but I know you will forgive me, as your Grandpapa has liked to have me with him so much, and I could not write and talk to him comfortably. All your notes have delighted me, my precious children, and show me that you have not quite forgotten me. I am always thinking of you, and longing to have you all round me again more than words can tell. God grant that we may find you all well and happy on Friday evening. I am happy to say your dearest Papa is quite well – his cough is rather tickling, but is of no consequence. …5

The letter continues: ‘It delights me, my darling Charlie, to hear that you are getting on so well with your Latin, and that you make so few mistakes in your Exercises,’ indicating that, at the age of 8, Dodgson had already begun to study the classical language of Latin, and probably Greek, too. Dodgson carefully preserved this letter from his mother, writing on the back: ‘No one is to touch this note, for it belongs to C. L. D.,’ with the addition: ‘Covered with slimy pitch, so that they will wet their fingers’, and as a result of this mock warning, the letter survived.

Life for Dodgson was not all schoolwork. There was time to play and time to entertain his growing number of brothers and sisters. He became adept at magic tricks and also showed some early talent at storytelling and writing poetry. The family made one long holiday to the Isle of Anglesey, visiting Beaumaris, which was reached by coach and horses via the Menai Bridge. This obviously made a great impression on him for, some years later, he made reference to the bridge in a poem entitled ‘Upon the Lonely Moor’ (1856), which was the early version of the White Knight’s ballad in Through the Looking-Glass.6 He wrote:

I heard him then, for I had just

Completed my design

To keep the Menai Bridge from rust

By boiling it in wine.

After sixteen years at Daresbury, a better living became available – a Crown living at Croft-on-Tees, near Darlington, on the Yorkshire/County Durham boundary, made vacant by the death of the incumbent, James Dalton (1764–1843). Various friends, including Charles Thomas Longley (1794–1868), bishop of Ripon, encouraged the prime minister, Robert Peel (1788–1850), to offer this more lucrative position to Dodgson’s father. The pleas were successful and Dodgson’s father was appointed rector of Croft. When the family moved to Croft-on-Tees in 1843, Richmond School was close at hand and Dodgson began his formal education there, becoming a boarder at the age of 11. The next eighteen months were preparation for his main education at Rugby School, which began in February 1846. Again, he excelled in mathematics, but he was also proficient in scripture, Latin and Greek. Hence, it was a foregone conclusion that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and matriculate at Christ Church, Oxford. He began his undergraduate studies at the University of Oxford in January 1851 but within two days his mother died suddenly and unexpectedly and he rushed back home for the funeral.

The death of his mother at such an early stage in his life probably affected his outlook thereafter, revealing to him that mortality was ever present. She was, by all accounts, a loving and gentle mother who devoted her entire existence to her growing family. Her characteristics were reflected in her eldest son. Dodgson cared about the well-being of others and he exercised responsibility from an early age, becoming the natural leader of his siblings. Dodgson was aged 19 when his mother died. The family of eleven children was now in a difficult situation and this created a serious need for a mother-substitute – someone to look after the younger members of the family. His mother’s spinster sister – Lucy Lutwidge – stepped in to fulfil this role and she remained with the family for the rest of her life.

Lucy Lutwidge: Surrogate Mother

Lucy Lutwidge was the third daughter of Charles Lutwidge and Elizabeth Anne Dodgson. She was born in 1805 in Kennington, Middlesex, two years aft...