![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE TRIBES OF THE NORTHERN

ALBANIAN ALPS

(MALËSIA E MADHE)

The Kelmendi Tribe

Location of Tribal Territory

The Kelmendi tribal region is situated in the present District of Malësia e Madhe in the most northerly and isolated portion of Albania. The core of this region is the upper valley of the Cem (Cijevna) River. Kelmendi borders on the traditional tribal regions of Gruda and Triepshi to the west, Hoti to the southwest, Boga to the south, Shala to the east and on Slavic-speaking tribes to the north. The administrative centre of this region, which consists mostly of canyons and deep valleys, is now the village of Vermosh. The main settlements of Kelmendi include: Vermosh, Tamara, Selca, Lëpusha, Vukël and Nikç.

Population

The name Kelmendi was first recorded in an Ottoman tax register in 1497 as Kelmente1 and as nahiye Kelmenta (district of Kelmendi).2 The Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi (1611–85), who journeyed through northern Albania in 1662, referred on numerous occasions to the infidel tribe of Klemente or Kelmendi. The ecclesiastical report of Pietro Stefano Gaspari recorded the form Clementi in 1671, as did the map of the Venetian cartographer Francesco Maria Coronelli in 1688 and the map of the Italian cartographer Giacomo Cantelli da Vignola in 1689. The term Kelmendi, with its early variants Klmenti, Klmeni, Klimenti and Clementi, was at any rate known in western Europe in the seventeenth century. Kelmendi, which is also a common family name, in particular in Kosovo, is commonly said to be related to the Latin personal name Clementus or to Saint Clement, borrowed into Albanian through the influence of the Catholic Church, but it is likely that the tribal designation is earlier than the association with Saint Clement. There was, at any rate, a church of Saint Clement in Vukël that was built by the Franciscans in 1651.3

Figure 1.1 A Kelmendi man and woman (copperplate etching by Jacob Adam of Vienna, 1782)

Figure 1.2 Idriz Lohja and his family, of the Lohja tribe

In 1614, the Kelmendi tribe is reported by the Venetian writer Marino Bolizza to have consisted of 178 households and 650 men in arms, commanded by Smail Prentasseu and Pedda Sucha.4 He describes them as an untiring, valourous and extremely rapacious people. In a report to the Congregation of the Propaganda Fide in 1634, Gjergj Bardhi (Giorgio Bianchi), the Bishop of Sappa, informs us that the Kelmendi consisted of 300 houses and 3,200 inhabitants.

In 1838, the Austro-Hungarian physician Joseph Müller was informed by a Pater Deda of Vukël that there were 4,200 inhabitants in Kelmendi.5 At about the same time (1841), in his ‘Brief Information on the Tribes of High Albania, in particular on the Independent Mountains’, Nicolay, Prince of the Vasoyevich, gave the population of Kelmendi as 2,000, of whom 500 were men in arms.6 In 1866, Emile Wiet, the French consul in Shkodra, noted 510 households comprising a total of 3,263 people.7 In the late nineteenth century, we can thus estimate the population of the Kelmendi tribe at some 4,000.

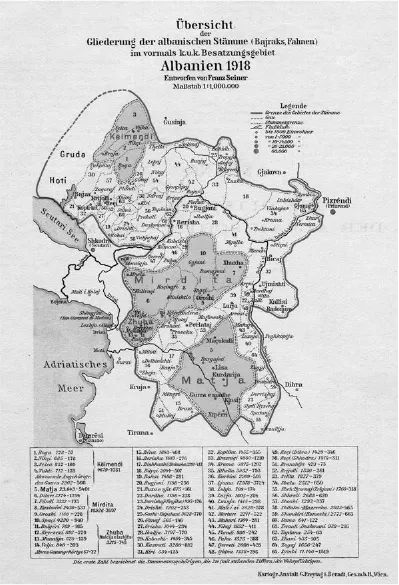

Figure 1.3 Classification of the Albanian tribes by Franz Seiner, 1918

In the first reliable census taken in Albania in 1918 under Austro-Hungarian administration, the population statistics of the Kelmendi tribe were given as follows: 779 households with a total of 4,679 inhabitants. This comprised the bajraks of Nikç, Vukël, Selca and Boga, and the settlements of Nikç, Broja, Vukël, Selca, Vermosh, Kolaj and Preçaj.8

The Kelmendi were and are a Catholic tribe, although a small minority converted to Islam in the Turkish period. The parish of Selca was founded in 1737 when the first births and deaths were recorded.9 Their patron saint is the Virgin Mary, called Our Lady of Kelmendi (Zoja e Kelmendit), whose feast day is celebrated on 24 May.

The apostolic visitor to Albania, Pietro Stefano Gaspari, who travelled through the region in 1671–2, reported:

On 24 September 1671, we left the land of Hotti and reached Clementi [Kelmendi]. There is a church here dedicated to Saint Clement. It is situated in a place called Speia di Clementi. The church was built by the people of Clementi in 1651, when the reverend Patres Reformati entered the country. Father Leone of Cittadella and Brother Angelo of Milan were serving here. It is done in whitewash without mortar, and covered in planks. It was well looked after and is furnished with holy vestments. But the Eucharist is not held here, although there is no danger from the Turks, as there are no such individuals in this place.

Clementi has a number of villages: Morichi with 6 homes and 40 souls, Genovich with 7 homes and 60 souls, Lesovich with 15 homes and 120 souls, Melossi with 7 homes and 40 souls, Vucli [Vukël] with 32 homes and 200 souls, Rvesti with 6 homes and 30 souls, Zecca with 7 homes and 40 souls, Selza di Clementi [Selca], together with Morichi has 34 homes and 290 souls, and Rabiena and Radenina with 60 homes and 400 souls. All of these villages use the church of Saint Clement in Speia. They go there to attend mass and receive the holy sacraments, and when they die, they are buried in this church.

The plateau of Clementi and the plateau of Nixi [Nikç] and Roiochi have 112 homes and 660 souls. It is a good 12 miles to Clementi. The Patres Reformati come here two or three times a month to celebrate mass and assist the people in their spiritual needs. There is a need here for vestments because it is very difficult for them to be transported here from Clementi every time. They call it the plateau of Clementi because the Clementi tribe constantly harassed the inhabitants of this area and took over their land. The plateau is fertile and the people of Clementi can make a living off it.10

The Kelmendi were a fis, i.e. a community that is aware of common blood ties and of a common history reaching back to one male ancestor, and were divided into three bajraks (Selca, Vukël and Nikç) and later, around 1897, with the addition of Boga, into four bajraks. The Boga were actually a separate tribe living to the south of the Kelmendi region, on the other side of a high mountain range, and had closer contacts with Shkreli and Shala, but they turned to the Kelmendi for protection and gradually became affiliated with them.

At least from the mid-nineteenth century, like many of the northern tribes, the Kelmendi drove their herds down to the coast every autumn where they spent the winter months. They shared pastureland with the Shkreli and Rrjolli tribes on Mali i Rrencit. Edith Durham described the trek of the Kelmendi of Selca as follows:

Each autumn the tribesmen migrate with great herds of goats, cattle, and sheep to seek winter pasture on the plains near Alessio [Lezha], where the tribe owns land, the women carrying their children and their scant chattels upon their backs; and toil back again in summer to the pastures of the high mountains, a long four days' march with the weary beasts.11

Baron Nopcsa, who was in the northern mountains at about the same time as Durham, noted this phenomenon, too:

Among the transhumant shepherds that are common throughout the Balkans are the Kelmendi, as well as the Hoti, Kastrati, Boga and Shkreli. For the sake of their herds they are forced to have two homes: winter quarters on the plains and summer quarters up in the mountain pastures. According to Hecquard, these mountain tribes have been spending the winter on the broad plains of the Boyana, Drin and Mat Rivers along the Adriatic since 1847. It must, however, be noted that not all of the tribesmen change residence, only those who do not have suitable winter pastureland in their own territory. Of the Kelmendi, it is probably more than a third of them who move. In early September, the various families begin the trek down to the plains of Shkodra and Lezha. Their movements can be traced from the Montenegrin border near Gucia [Gusinje] right down to the lofty fortress of Kruja, a distance of 140 kilometres as the crow flies. Everywhere one looks on the otherwise monotonous plain of Shkodra one can see the shepherds and their flocks, including some quite interesting and picturesque groups. Whenever there is a lack of fodder in the mountains, the members of other tribes, too, such as the Shala and even the Rugova highlanders from the region of Peja [Ipek] move down to the Adriatic coast. In the winter of 1908, I encountered Rugova tribesmen and their herds in the region around Durrës. Although it is rather difficult to calculate just how many people wander as nomads each year in search of winter fodder, I would think there are at least 4,000 to 5,000 of them. I rely in this calculation on the estimation that of the 5,000 tribesmen of Kelmendi, almost half of them take part in the trek and that their exodus is increased substantially by the other, though smaller tribes – the Hoti, Kastrati, Shkreli, and Boga. The flocks of animals and shepherds are bottled up for several weeks in and around Trush near Shkodra until they take to the hills between Zadrima and the sea, or regain their winter quarters along the banks of the Mat River.12

Some of these Kelmendi families, indeed, settled on the coast around Lezha for longer periods. Johann Georg von Hahn reported in the mid-nineteenth century:

For about the last ten years they have begun purchasing the land that they have used for centuries for grazing purposes, thus impeding any agricultural usage. They have now begun to transform it into farmland. The surprising results at the start of this endeavour will probably lead to further success. The average harvest of the richest Kelmendi is 300 horsewaggons of grain at 80 oka.13

Their stay on the coast and contact with the outside world enabled the Kelmendi to progress intellectually. Many of them learned to read and write in the early years of the twentieth century, without the help of schools. They began to look down on the neighbouring Shala as savage and filthy, gjin të egër (wild folk), as they stated, and made fun of their bug-ridden state.14

On his travels through Kosovo in 1858, which he calls Dardanian Albania, Hahn noted the presence of the Kelmendi tribe in the Llap valley around Podujeva in northeastern Kosovo and in neighbouring Serbia:

Of the 22 villages of Lab [Llap], 20 of them are Clementines [Kelmendi]. The other two belong to Betush [Bytyçi]. They extend from Podujeva to Kurshumlija and inhabit most of the villages in Dedić. On the other hand, there are no Kelmendi in the regions of Vranje and Gilan [Gjilan]. They all regard the Kelmendi, who inhabit the northern Albanian Alps and are of Catholic faith, as their mother tribe, from which at various times individual families moved to Dardania.15

Among the main families of Kelmendi are the following, divided here according their usual places of residence in the tribal region:

in Vermosh: Bujaj, Bunjaj, Cali, Hasanaj, Hysaj, Lelçaj, Lekutanaj, Lumaj, Macaj, Miraj, Mitaj, Mërnaçaj, Naçaj, Peraj, Pllumaj, Preljocaj, Racaj, Selmanaj, Shqutaj, Tinaj, Vukaj, Vuktilaj, and Vushaj;

in Selca: Bikaj, Bujaj, Lekutanaj, Mërnaçaj, Miraj, Pllumaj, Rugova, Tinaj, Vukaj, Vushaj;

in Tamara: Bujaj, Bunjaj, Cekaj, Lelcaj, Mërnaçaj, Rukaj and Vukaj;

in Vukël: Aliaj, Dacaj, Drejaj, Gjelaj, Gjikolli, Kajabegolli, Martini, Mirukaj, Nicaj, Nilaj, Pepushaj, Vucaj, Vucinaj and Vukli;

in Nikç: Aliaj, Gildedaj, Hasaj, Hutaj, Kapaj, Nikac, Nikçi, Prekelezaj, Preldakaj, Rukaj, Smajlaj and Ujkaj.

Tribal Legendry, Ancestry and History

Of all the tribes of the north, the Kelmendi were perhaps the best known to the outside world. Indeed, in the seventeenth century, the northern Albanian mountains west of Peja were often referred to simply as the ‘mountains of Kelmendi’.16 The Austro-Hungarian consul in Shkodra, Friedrich Lippich, Ritter von Lindburg (1834–88), described them in 1878 as the strongest of all the Catholic tribes in the highlands of Shkodra.17 Baron Nopcsa who recorded their oral history in 1907 noted that they were the tribe most referred to of all,18 and Edith Durham spoke of them as ‘some of the finest and most intelligent of the tribesmen’.19

In popular lore, the Kelmendi were known among the mountain tribes for their heroism, as reflected in the popular saying: ‘The wisdom of the Gashi, the watchfulness of the Krasniqja, the wrath of the Berisha, the heroism of the Kelmendi, the slyness of the Shala, a snake in the grass like the Thaçi’ (Mênja e Gashit, sŷni i Krasniqes, inati i Berishës, trimnia e Kelmênit, dredhia e Shaljanit, gjarpnia e Thaçit).

In oral tradition, the Kelmendi tribe is said to stem from a figure called Klement or Kelmend who, according to Baron Nopcsa's estimate, lived around the years 1470–80. French consul Hyacinthe Hecquard (1814–66) narrates that this Kelmend, a runaway priest, settled in Triepshi where he worked as a shepherd for a rich herdsman who had an aging daughter called Bubçe.20 Kelmend and Bubçe fell in love and she became pregnant. Her father wanted to kill the couple, but let them marry at the insistence of his wife. Bubçe received 20 head of sheep on condition that she and Kelmend leave Triepshi and never return. They moved to a place called Bestana at the foot of Mount ‘Gascianik’21 on the Cem, and had numerous sons. In one version of the legend, Kelmend is said to have two sons: Kol who founded the settlement of Selca, and Nish or Nika who founded the settlement of Nikç.22 Other versions of the legend give the said Kelmend as having a larger numbers of sons – seven to nine – who at any rate were considered the ancestral fathers of the settlements of Selca, Vukël and Nikç. These sons had children of their own until Bestana became too small to hold them. They thus emigrated and settled in the fertile valley of Gucia [Gusinje] where they were occasionally in conflict with their neighbours and with the Turks.

Johann Georg von Hahn heard the legend of the founding of the Kelmendi tribe from a Father Gabriel in Shkodra in 1850 and recounted it as follows:

Many years ago, there was a rich herdsman in the region of Triepshi. A young man of unknown origin called Klement came by and was employed by the herdsman to take care of his sheep. This the shepherd did together with the herdsman's daughter who was called Bubci. She was lame and had thus not been able to find a husband. With time, their friendship developed into a love affair and the maiden became pregnant. When the girl's mother found out what had happened, she used all the means at her disposal to persuade her rough and heartless husband not to punish the young couple but to allow them to live together. According to custom, he had the right to put them to death. In the end, she succeeded and Klement and ...