![]()

1

DISCERNING AND ASSESSING PUBLIC VALUE

MAJOR ISSUES AND NEW DIRECTIONS

JOHN M. BRYSON, BARBARA C. CROSBY, AND LAURA BLOOMBERG

This chapter explores the meaning of value, compares Moore’s and Bozeman’s views of public value, connects public value to concepts like the public interest, and suggests how different public value approaches might be integrated. Because a workable public sphere is vital to conceptions of public value, we also consider the meaning of the public sphere.1

THE MEANING OF VALUE

For most readers, the term “value” is straightforward, meaning “relative worth, utility, or importance” (“Value” n.d.).2 This commonsense definition, however, begs a number of questions apparent in the current debate over public values, public value, and the public sphere (Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman 2007; Rutgers 2008). These questions concern at least the following: (1) whether the objects of value are subjective psychological states or objective states of the world; (2) whether value is intrinsic, extrinsic, or relational; (3) whether something is valuable for its own sake or as a means to something else; (4) whether there are hierarchies of values; (5) who does the valuing; (6) how the valuing is done; and (7) against what criteria the object of value is measured. The chapters in this book demonstrate the variety of ways in which these questions can be addressed productively.

TWO CONTRASTING VIEWS OF PUBLIC VALUE

What we will call the public value literature includes the related themes of public value, public values, and the public sphere, in which the adjective “public” before value, values, and sphere extends well beyond government purview. This body of work has grown dramatically in recent years.

Based on an extensive review of the literature, Williams and Shearer (2011) find an increasing popularity of the concept of public value (singular) within both academic and practice settings. Indeed, Stoker (2006) argues that a new paradigm he calls “public value management” is emerging to replace “traditional” public administration and what has been called the new public management. Similarly, Van der Wal, Nabatchi, and de Graaf (2013) assert that “the study of public values [plural] is not only gaining in importance in our field [but] might be one of the most important themes.” Finally, scholars and practitioners have paid substantial attention to the public sphere, whether in terms of government’s proper role (e.g., Kettl 2002, 2008; Osborne and Hutchinson 2004; Goldsmith and Eggers 2004), public engagement (Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006; Bryson et al. 2013; Nabatchi and Leighninger 2015), active citizenship (e.g., Boyte 2005, 2011), or the desire for strengthened democracy (e.g., Fung 2003; Nabatchi et al. 2012).

In this section we focus on the two main strands of the public value literature. The first, developed by Mark Moore and his colleagues, is a managerial action-focused concept of creating public value, while the second is Barry Bozeman’s and his colleagues’ policy and societally focused conception of public values. In the next section we attend to the public sphere, the third main theme in the literature. In the section after that we present a conceptual framework that incorporates all three perspectives and discuss ways of integrating them in practice.

Mark Moore on Creating Public Value

Mark Moore’s 1995 landmark book Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government helped popularize the language of public value and suggested how it might be realized in practice. Moore explicitly offered the language of “creating public value” as a counter to the more dominant language of creating shareholder value and to the assumption that government is suspect and businesses are more legitimate. The book concentrated specifically on what US public managers—meaning in this case government managers—could do that would benefit the public and that the public would value as well. The action focus was managerial, while the desired outcome was organizations that meet (or can appropriately and legitimately change) their mandates; generate political support in such a way that they can deliver public value and what the public values; and do so efficiently, effectively, accountably, justly, and fairly in the context of democratic governance. Public value is thus a summary term assessed and measured against the extent to which it achieves or realizes in practice more specific public values at reasonable cost.

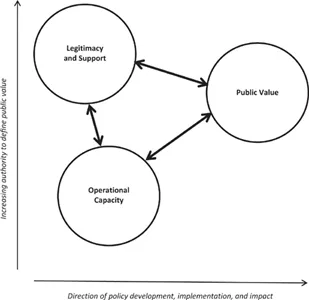

Moore’s approach is a normative, doctrinal argument about what public managers should do and how they should develop appropriate strategies. For this latter task he directs attention to what he calls the strategic triangle (see figure 1.1), which involves finding appropriate ways of taking into account the “authorizing environment” of mandates and political support, doing what is necessary to create operational capability to produce results, and actually delivering public value to the citizenry at reasonable cost. The strategic triangle thus incorporates input, process, output, and possible outcome measures, although the public value “point” to the triangle is essentially about outputs and outcomes. Moore’s work has had a significant impact on public management thinking in the United States and has been particularly well received in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries. In more recent work Moore has related his public value theory more thoroughly to democratic values, institutions, and processes (Moore 2013, 2014). He also has applied the strategic triangle to nonprofit organizations (Moore 2000).

Figure 1.1 The strategic triangle

Source: Reprinted by permission of the publisher from Mark H. Moore, Recognizing Public Value (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 103. Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

In this book Moore makes a significant contribution to answering the question of how to discern, measure, and assess public value in his chapter on public value accounting.

In terms of the questions about the meaning of value, for Moore public value generally refers to objective states of the world that can be measured. Moore also sees public value in a democracy as extrinsic, intrinsic, and relational. Something being evaluated may be deemed to hold inherent value or may be seen as a means to something else, as reflected in the criteria used to assess it. Moore does assume a hierarchy of values in which effectiveness, efficiency, accountability, justness, and fairness are prime. For Moore, elected officials and the citizenry are the ultimate arbiters of value, but public managers also play an important role in valuing. He presents the public value account and public value scorecard as aids for assessing value.

Moore’s approach has received sharp criticism, particularly from R.A.W. Rhodes and John Wanna (2007). They note that at varying times its proponents view it as “a paradigm, a concept, a model, a heuristic device, or even a story. . . . [As a result,] it is all things to all people” (408). Rhodes and Wanna also charge that Moore’s approach downplays the importance of politics and elected officials, overemphasizes the role of public managers, and trusts too much in public organizations, private-sector experience, and the virtues of public servants (409–12).

John Alford (2008; see also Alford and O’Flynn 2009) mounts a spirited defense of Moore and refutes each of Rhodes and Wanna’s points. He emphasizes Moore’s strategic triangle that gives the authorizing environment a crucial role to play in placing “a legitimate limit on the public manager’s autonomy to shape what is meant by public value” (177). Alford believes Rhodes and Wanna operate out of an “old” public administration paradigm that draws a sharp distinction between politics and administration and do not recognize that political appointees and civil servants often have considerable justifiable leeway to influence policy and decisions in the face of unavoidable ambiguity and uncertainty.

Adam Dahl and Joe Soss (2014) also criticize Moore’s conception of creating public value. In their view, by posing public value as an analog to shareholder value, seeing democratic engagement in primarily instrumental terms, and viewing public value as something that is produced, Moore and his followers mimic the very neoliberal rationality they seek to resist and run the risk of furthering neoliberalism’s de-democratizing and market-enhancing consequences. Public managers might unwittingly be agents of “downsizing democracy” (Crenson and Ginsberg 2002). The cautions Dahl and Soss raise are serious and should be addressed by those seeking to advance the public value literature; Moore himself addresses these concerns in chapter 8.

In addition, Lawrence Jacobs (2014) questions Moore’s hopeful view of public management in the United States, given sharply divided public opinion on many issues, intensely partisan politics, the power of organized interests, and the many veto points built into governance arrangements. Clearly, public managers are constrained in a democratic society—and rightly so—but many examples of enterprising, public value-producing activities also demonstrate public managers can be active agents in creating public value. The public value literature thus should explore much further the conceptual, political, organizational, managerial, and other opportunities and limits on public managers’ seeking to create public value in particular circumstances. The chapters in this book contribute to this exploration.

Barry Bozeman on Public Values

In contrast to Moore’s managerial action focus, Barry Bozeman’s 2007 book, Public Values and Public Interest: Counterbalancing Economic Individualism, significantly expanded the conversation to the policy or societal level and highlighted the intersection of market successes and failures with what he calls public value successes and failures. The action focus is thus broader than management, and the view of public value is even more emphatically normative as well as more specific than Moore’s. The book explicitly takes issue with the dominance, especially in the United States, of economic individualism and the neoliberal agenda embodied in the new public management (Hood 1991; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2011). Bozeman’s work has had a significant impact on public management thinking in the United States and abroad.

Bozeman (2007, 17) begins by defining public values as “those providing normative consensus about the rights, benefits, and prerogatives to which citizens should (and should not) be entitled; the obligations of citizens to society, the state, and one another; and the principles on which governments and policies should be based.” Bozeman’s definition implies that public values in a democracy are typically contested, meaning the consensus on them is hardly ever complete. Nonetheless, in operational terms one can discern relative consensus on public values from constitutions, legislative mandates, policies, literature reviews, opinion polls, and other sources (Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman 2007).

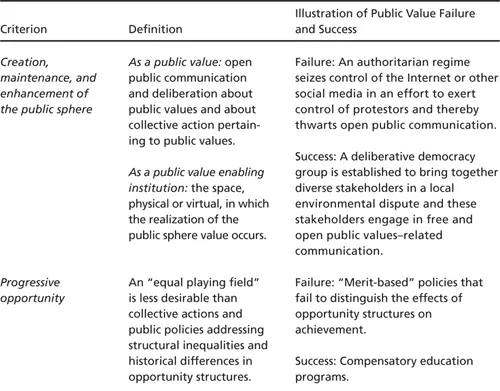

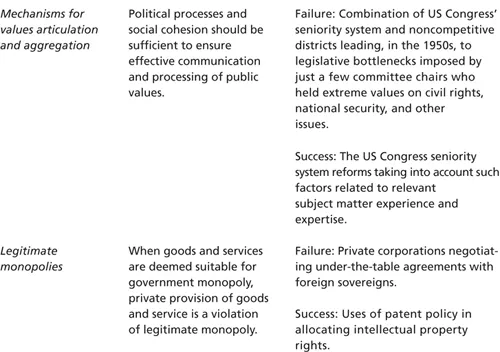

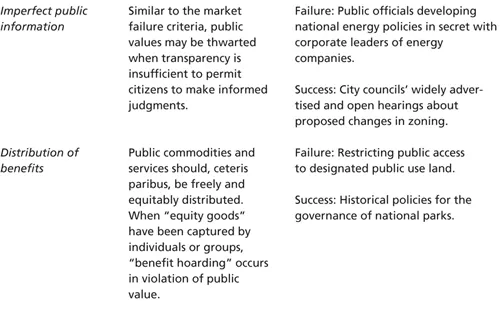

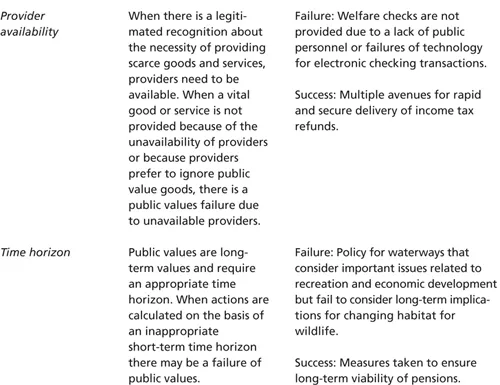

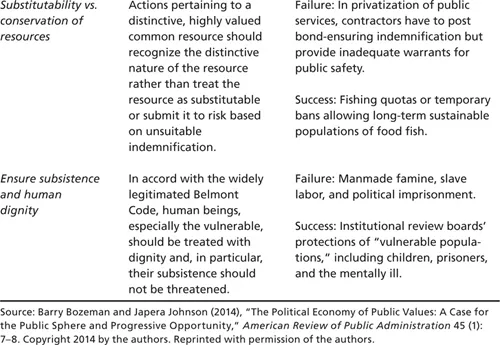

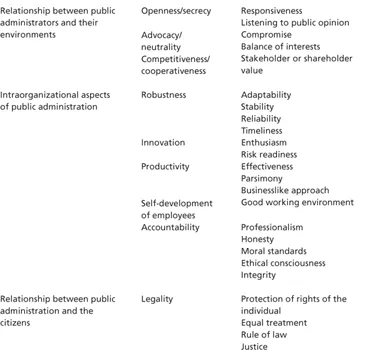

What Bozeman terms public values “failure” occurs when neither the market nor the public sector provides goods, services, or enabling institutions required to achieve public values. As a way of helping understand whether public value successes or failures have occurred, Bozeman and Japera Johnson (2014) propose a set of ten public values criteria, which are presented in table 1.1 (Bozeman 2002, 2007; Bozeman and Johnson 2014). The criteria in part mirror market failure criteria and combine input, process, output, and outcome measures. Public value creation can be conceived as the extent to which public values criteria are met. Public values for Bozeman thus are measureable, although clearly there can be disagreements about how the values are to be conceptualized and measured.

Bozeman has developed a “public value mapping process” that juxtaposes public value and market successes and failures in order to create a matrix onto which particular policies may be “mapped.” The process produces a picture of the nature and extent of public value created by a policy. In this book Bozeman and his coauthors Jennie Welch and Heather Rimes contribute a chapter detailing the public value mapping (PVM) process.

One implication of Bozeman’s approach is that analysts, citizens, and policy-makers should focus on what public values are, and on ways in which institutions and processes are necessary to forge agreement on and achieve public values in practice (Davis and West 2009; Jacobs 2014; Kalambokidis 2014).

Note that Bozeman’s approach is both positive, when he asks what the normative consensus on values is, and normative, when he argues that public values failures should be corrected. Bozeman (2007) is relatively silent on the role of the nonprofit sector; on the rights, responsibilities, or weights to be given to non-citizens; and on the role and importance of power in contests about public values. Regarding the effects of political power, Jacobs (2014) believes that in the US context Bozeman in his 2007 book severely underestimates the extent of dissensus, the disproportionate influence of affluent citizens and organized interests, and the extent to which governing structures favor inaction and drift. More recently, Bozeman has rectified some of these concerns; he and Johnson have added as public value criteria the creation, maintenance, and enhancement of the public sphere and progressive opportunity, defined as addressing structural inequalities and historical differences in opportunity structures. The changes are reflected in table 1.1 (Bozeman and Johnson 2014).

In terms of the questions about value noted above, for Bozeman, like Moore, public values are objective states of the world that can be measured. Also like Moore, public value in a democracy is extrinsic, intrinsic, and relational. Again like Moore, a policy or other object being evaluated may hold inherent value or may be seen as a means to something else; this will be reflected in the specific criteria used to judge it. Unlike Moore, Bozeman posits no preordained hierarchies of values. Citizens, managers, public officials, and other groups can and do apply the market and public value success and failure criteria. Makers of a PVM identify important values by assessing a variety of documents and other sources.

Table 1.1. Public values criteria

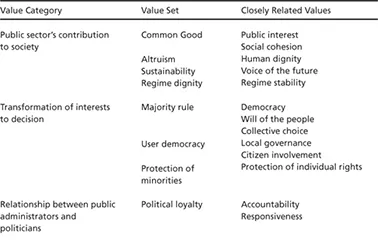

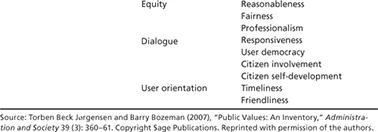

Bozeman joined with Torben Beck Jørgensen (Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman 2007) in developing an inventory of public values found in the public administration literature (see table 1.2). They identified seven “constellations” of public values: (1) the public sector’s contribution to society, (2) transforming interests to decisions, (3) the relationship between public administrators and politicians, (4) the relationships between public administrators and their environment, (5) inter-organizational aspects of public administration, (6) the behavior of public employees, and (7) the relationships between public administration and the citizens. A more complete list would also articulate the relationship between public officials and society and between citizens and society. (Thomas, Poister, and Su in chapter 11 add the quality of agency working relationships with legislators and others.) The constellations of values touch on all three points of Moore’s strategic triangle.

Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman also made an important distinction between “instrumental” and “prime” public values, meaning values that help achieve other values and values that are ends in themselves. Other scholars have taken different approaches to cataloging public values; for example, Stephanie Moulton (2009) ties sets of values to institutions and Lotte Andersen and colleagues (2012) assign different values to archetypal forms of government organizations.

Table 1.2. Elicited public values, by category

A Note on the Psychological Sources of Public Value

Timo Meynhardt (2009), in an important though less widely cited approach, takes a very different tack from the previous authors. He is particularly interested in the philosophical and psychological roots of valuing. He concludes that valuing is ultimately both psychological and relational and that public value is constructed out of “values characterizing the relationship between an individual and ‘society,’ defining the quality of the relationship” (206). The relationship’s quality is assessed subjectively by individuals, but when there is intersubjective weight attached to these assessments, they become more objective and quantified and might ultimately reach Bozeman’s requirement of a reasonable normative consensus. Meynhardt believes that public value is for the public when it concerns “evaluations about how basic needs of the individuals, groups, and the society as a whol...