![]()

1.

What is Justice?

The purpose of this Little Book is to identify some characteristic features of the Bible’s teaching on justice. Christians regard the Bible as a uniquely important source of guidance on matters of belief and practice. What the Bible has to say about justice therefore—both social justice and criminal justice—ought to be of great significance for Christian thought and action today.

The Bible also has had a profound impact on the development of Western culture in general. So exploring biblical perspectives on justice can help us appreciate some of the convictions and values that have helped shape Western political and judicial thought in general.

Yet coming to grips with biblical teaching on justice is by no means easy. There are many complexities to cope with.

• There is a huge amount of data to deal with. There are hundreds of texts in the Old and New Testaments which speak explicitly about justice, and hundreds more which refer to it implicitly. Justice is in fact one of the most frequently recurring topics in the Bible.

• The data is also diverse. Different biblical writers address different historical circumstances, and they sometimes take different positions on what justice entails (especially with respect to criminal justice). In this Little Book we will concentrate on broad areas of theological agreement among the writers. But we do well to remember that, especially on issues of justice, the difficulty is always in the detail.

• We also always need to remember that biblical reflection on justice takes place within a larger cultural and religious worldview that is, in many respects, quite unlike that of contemporary secular society. Understanding the justice dimension of biblical teaching requires us to cross over into a different world from our own, and this is never an easy thing to do.

Added to these factors are the complexities that surround the concept of justice itself. What actually is justice? Does justice have an objective existence, or is it simply the product of social agreement? Is there an unchanging essence to justice—such as fairness or equality or balance—or does it mean different things to different people in different settings? Where does justice come from? How is justice known? How should it be defined? What is the relationship between justice, love, and mercy?

These are all very difficult questions which we cannot explore in any detail here. But even without traversing the difficult terrain of moral and legal philosophy, it is evident from everyday discourse that justice is a paradoxical value.

The Justice Paradox

Justice is one of those ideas that combines tremendous emotional potency with a great deal of semantic ambiguity. It is both a self-evident reality and, at the same time, a highly disputed one. Let’s consider each side of this paradox:

• On the one hand, we all have a strong intuitive sense of what justice is. We appeal to the criterion of justice all the time. We instinctively recognize when it has been violated. Even very young children have a powerful, innate sense of justice. Think of how often children complain that something is just so unfair! To declare some action or state of affairs to be unfair or unjust is to make one of the strongest moral condemnations available. And when individuals make this complaint, they usually assume that the injustice in question will be patently obvious to anyone who cares to look.

• But what appears obvious to one person is not always obvious to others. People may agree that justice is the fundamental principle to consider, but they frequently disagree on how the principle translates into practice. Some, for example, defend capital punishment as a matter of just deserts, a life for a life, the rebalancing of the scales of justice. Others decry it as an affront to human dignity, an awful imitation of the injustice it claims to denounce or correct.

Or again, some consider it to be a matter of basic justice that women have the right to choose an abortion, since it is their bodies that are affected. For others, however, abortion is a deadly injustice to an unborn child, the unjustifiable taking of innocent human life.

Similar disputes on justice litter human history, and there have been huge shifts in social consensus from age to age. Aristotle considered slavery to be compatible with, even essential to, a just society. For later British and American abolitionists, slavery was the very epitome of injustice.

So we have a paradoxical situation. We all know that justice is important, we all feel obligated towards the demands of justice, we all sense the primordial pull of justice. But we cannot say exactly what justice is, or how best to define it, or why standards of justice vary so much through the centuries and across different cultures.

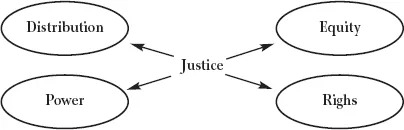

Key Conceptual Components

Obviously justice is not a straightforward or singular concept. Like love, justice is a generic or inclusive term embracing a variety of meanings and applications. This makes it very difficult to reduce justice to a simple, all-encompassing definition. Yet most expositions of justice seem to involve at least four key ingredients:

• Distribution: Justice entails the appropriate distribution of social benefits and penalties among contending parties. Justice dictates that people get their fair share in society’s goods and rewards (social justice), and that they are not subjected to punishments or penalties unless they morally deserve them (criminal justice).

• Power: Justice involves the exercise of legitimate power—whether to arbitrate between conflicting claims, to implement social benefits, to enforce legal obligations, or to impose suitable sanctions. Injustice occurs when power is misused to deny or rob people of what they are rightfully due.

• Equity: Justice requires fairness and balance. Similars should be treated as similars, and dissimilars as dissimilars. Disputes should be adjudicated even-handedly, without regard to irrelevant, secondary considerations that would arbitrarily disadvantage one party.

• Rights: Justice has to do with honoring the rights or entitlements of people, especially in conflict situations. A right exists when someone has a legitimate moral or legal claim on some good, which others have a duty to respect or uphold. Justice gives moral legitimacy to such rights.

At the broadest level, then, justice entails the exercise of legitimate power to ensure that benefits and penalties are distributed fairly and equitably in society, thus meeting the rights and enforcing the obligations of all parties.

So far so good. Disputes arise when deciding questions like these: Who should exercise power? What kind of power is appropriate? What benefits or penalties do particular parties deserve? What constitutes a fair distribution of resources in view of the different characteristics and contributions of people? Whose rights take precedence when there is a clash between the legitimate rights or claims of various groups?

Making decisions in such disputes is never easy. It requires careful consideration of all the factors bearing on each situation. How these factors are distinguished and measured depends, in turn, on the larger worldview or belief system within which human communities operate. It is here that justice intersects with religious understandings and meanings. Those beliefs, values, stories, and symbols that make up a worldview are, by definition, religious in nature inasmuch as they presuppose or give answers to life’s ultimate questions.

Most philosophers now agree that the content of justice cannot be determined simply through the exercise of objective, disembodied reason. No such faculty exists. Reason does not operate in splendid isolation from the rest of human experience. Human beings can only ever think about justice (or anything else for that matter) within the context of particular historical and cultural traditions. In other words, our reasoning, and thus our understanding of justice, is unavoidably contextual or historical in character. This need not mean that justice itself is merely the product of human reflection, that it has no objective, transcendent existence. It simply means that our knowledge of actual justice is always going to be limited and partial.

From a Christian perspective, justice must have a real objective existence, because justice derives from God, and God exists apart from human speculation. Justice is real because God is real. But our capacity to know God’s universal justice is unavoidably conditioned by the ways of looking at life and the world which we receive from the particular historical and religious traditions to which we belong. This is where the Bible comes in.

The Bible’s Contribution

Christians can be confident not only that justice exists because God exists, but that it is possible to know something substantial about the nature of justice, just as it is possible to know something substantial about the nature of God. And the place to learn about justice, first and foremost, is the biblical narrative of God’s creative, sustaining, and redeeming activity in the world.

For the biblical writers, the meaning of justice is not discovered through abstract philosophical speculation. It is known primarily through God’s revelation in history, and the biblical writings comprise the record of that revelation. It is from the biblical story of God’s self-disclosure, in both word and deed, that we can come to understand more of what justice entails.

In the biblical narrative, two events stand out as uniquely important in understanding God’s justice. The first is the liberation of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt and their formation into a covenant community living under God’s law. Over and over again, the prophets and poets of Israel declare that God’s justice has been made visible in this momentous intervention.

We learn what justice is from the biblical story of God’s self disclosure.

The second great event is the coming of Jesus Christ, who also brings deliverance from servitude and inaugurates a new covenant. For the New Testament writers, the Christevent, even more than the exodus from Egypt, is the decisive “revelation of God’s justice” (Romans 1:16-17; 3:21-26).

In between and around these two great events, the biblical writers speak eloquently and repeatedly of justice, both divine justice and human justice. Before trying to summarize what they say, a little more needs to be said about the theological worldview within which they talk of justice.

![]()

2.

Justice in the Biblical Worldview

This chapter sketches the understanding of justice that emerges from the wealth of biblical texts on the topic. This chapter also discusses some of the foundational convictions or core values of the biblical worldview that shapes its distinctive theology of justice. Many such beliefs or convictions could be mentioned, but five are notable for our purposes.

Foundations of biblical justice

Shalom

Covenant

Torah

Deed-Consequence

Atonement-Forgiveness

However, before commenting on each of these ideas individually, it is important to reiterate just how central the theme of justice is in the Bible.

A Central Theme

Justice is one of the most frequently recurring topics in the Bible. For example, the main vocabulary items for sexual sin appear about 90 times in the Bible, while the major Hebrew and Greek words for justice (mishpat, sedeqah, diskaiosune, krisis) occur over 1000 times.

Yet modern readers often fail to recognize how pervasive the notion of justice is in the Bible. This is partly because the key Hebrew and Greek terms are translated by a variety of Engl...