![]()

Part 1: 1789–1836

![]()

1: The Language of Terrifying Prophecy

DISUNION DEBATES IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC

The era of constitution making bequeathed to the young nation not only a legacy of compromise and indecision on slavery, but also the beginnings of a discourse in which politicians summoned images of disunion to advance their own regional and partisan agendas. The early years of the republic witnessed periodic appeals to disunion; slavery was often, but not always, the principal source of contention. In 1790 Southern and Northern representatives in Congress clashed over the twin issues of where to locate the capital and whether Congress should assume the Revolutionary War debts of the states. Assumption was a key piece of the fiscal agenda of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, whose reputation for brilliance was matched by his reputation for arrogance. In Hamilton’s view, the United States should aspire to be a manufacturing and commercial superpower, in the model of Great Britain; “Britain’s funded debt” had fueled the “extraordinary growth of the British economy.” Southerners in states, such as Virginia, that had already paid down their Revolutionary War debts saw Hamilton’s plan as biased toward the North. Because Hamilton’s assumption scheme would make the states “beholden to the federal government,” and would create a large national debt that would need to be paid down by new federal taxes, it raised the specter of “consolidation”: of aggrandizing the central government at the expense of local interests. The heavily indebted New England states, by contrast, eager for federal relief, viewed assumption as a “sine qua non of a continuance of the Union,” according to Jefferson’s memorandum on the controversy. With disunion threats on the lips of prominent Northerners and Southerners, Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton reached a compromise whereby, in exchange for the passage of an assumption plan, Southerners won the promise that the national capital, after a temporary stint in Philadelphia, would be moved to a location on the Potomac, safely within slave country. The first of the “great compromises” between North and South, the measure did little to close the widening rift between Hamilton and the Virginians. Indeed, Jefferson later disowned the compromise, asserting that it “was unjust, in itself oppressive to the states, and was acquiesced in merely for a fear of disunion.”1

In the midst of the assumption and residency controversy, the First Congress became embroiled in a bitter debate over slavery and the slave trade, sparked by an abolition petition presented to the lawmakers by the pioneering Quaker antislavery organization, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS). The petition, under the name of pas president Benjamin Franklin, contended not only that slavery and the slave trade were incompatible with the new nation’s charter, but also that Congress had the power and the obligation to terminate the slave trade prior to the end of the twenty-year waiting period stipulated in the Constitution. In response, irate representatives from the Deep South, led by William Loughton Smith of South Carolina (a pro-administration Federalist) and James Jackson of Georgia (a vocal critic of the Federalist administration), threatened disunion, reminding their Northern counterparts that they would never have agreed to enter the Union unless their property in slaves was guaranteed, and that the Southern states would never submit to an abolition scheme without civil war. Matthew Mason notes that these men and other such defenders of slavery in the early national era were not yet willing to assert, unequivocally, the morality of slavery. Their arguments on behalf of the institution were instead “experimental and directed mainly at fellow Southerners.” The same might be said of their threats—their intimations of disunion, like their justifications of slavery, served to deny the immorality of slaveholding and to disparage slavery’s opponents. At this moment in 1790, the experiment achieved the desired result: Madison intervened, in the spirit of compromise and indecision, to shepherd through a debate-ending resolution that denied Congress the authority to initiate gradual emancipation in the Southern states. But the strident tone of these early debates was nonetheless ominous—congressmen spoke a “language of honor” in which threats and accusations were wielded to make and break personal reputations, and to defend and promote regional interests. Certain Southern lawmakers were already cultivating a reputation for belligerence—capitalizing on the perception that “hot blooded” Southerners were more willing to resort to violence than their “cold blooded,” cautious, puritanical Northern counterparts.2

As if playing out The Federalist’s warning about the many possible sources of disunion, Southerners and Northerners clashed repeatedly in the 1790s over aspects of Hamilton’s program such as the apportionment of the Congress, the chartering of a national bank, and John Jay’s 1795 treaty with Great Britain. Although slavery was the “most obvious difference” between North and South, it was not the explicit focus of these debates. As Sean Wilentz observes, “Northerners, some of whom were still squabbling about emancipation in their own states, did not perceive an antislavery agenda behind Hamilton’s proposals.” Southern farmers and planters viewed the Federalist position on each of these issues as a bid to increase the power of manufacturing interests at the expense of agrarian ones. In every instance, Southern intimations of disunion looked backward and forward. They tapped anxieties and resentments about the founding itself, particularly anti-Federalist fears that government consolidation would undermine state sovereignty. But disunion talk also served warning that a new opposition party was consolidating, with a strong base among Southern and Northern agrarians alike, and would challenge the Federalists for control of the national government.3

Disgust with the rising spirit of partisanship suffused George Washington’s “Farewell Address” of 1796. To counter that spirit, Washington called on the American people to reassert their devotion to the Union. Only the Union, he said, could guarantee for the citizens of the new nation prosperity, security, and happiness; the country’s leaders had a responsibility to act not as partisans but as stewards of a sacred trust. Washington deplored regional jealousies as well as partisan ones; he explicitly argued that the North and South were economically dependent on each other and could thrive only in partnership. In his view, “Local sentiments must be replaced by a sacred attachment to the Union and the Constitution.”4

Although his speech quickly entered the annals of “sacred” American documents and contributed to the deification of Washington himself as the greatest single embodiment of the Union, it did little to stem the tide of partisanship or to discourage partisans, including Washington’s own followers, from invoking disunion. For intimations of disunion could prove efficacious not only as threats but also as accusations. Thus the Federalist press, as the nation’s “quasi-war” with France escalated in 1798, charged that Jefferson’s new Democratic-Republican Party (commonly abbreviated as the Republicans, but not to be confused with Lincoln’s Republican Party, which came on the scene in the 1850s) was in thrall to French Jacobin “anarchists.” Such traitorous support of bloodthirsty revolutionaries, the Federalists alleged, was a threat to national security. Moreover, Federalists maintained that Republicans were fomenting uprisings among disgruntled farmers in both North and South and would stop “nothing short of disunion”—synonymous here with class warfare—in their campaign to bring down John Adams and Alexander Hamilton. Invoking the specter of the Union’s downfall as a justification, the Adams administration used the Sedition Act, which criminalized dissent, to try to silence the Republican press.5

Republicans struck back in defense of free speech behind Jefferson’s and Madison’s Virginia and Kentucky resolutions. Drafted by Madison for the legislature of Virginia and by Jefferson for that of Kentucky, the resolutions—cast as a defense of the “true principles” of the Constitution and the Union—asserted that the federal government was a compact of the states, and that the Federalist abridgment of freedom of conscience and of the press was an unconstitutional assault on states’ rights. Because the resolutions appealed to the states to take the “necessary and proper measures” to oppose such federal “consolidation,” Jefferson’s and Madison’s words were later appropriated by nineteenth-century secessionists as a theory of disunion. But modern scholars have emphasized that the resolutions did not go so far as to assert the absolute sovereignty of the states; states’ rights was a political means, not an end, for Jefferson and Madison. They sought, in the name of constitutional fidelity, to galvanize the opposition, both in the South and in the Mid-Atlantic, and to channel its energies toward the upcoming congressional elections and presidential contest—the “hint of disunion” would serve paradoxically to unify the Republicans. This tactic failed to pay off in the 1799 congressional elections but succeeded in forcing the hand of President Adams. The “prospect of civil war” so “horrified” Adams that he forged a peace with France, “defusing the sectional crisis” and splitting his party—thus opening the way for the Democratic-Republican Party’s ascendancy in 1800.6

Republicans kept up a drumbeat of disunion accusations as the 1800 elections approached, charging that Federalists were to blame for the bitter political divisions in the country and that Republicans alone could unify the nation. Integral to this Republican argument was the notion that Hamiltonians were in the thrall of the British, inviting Britain’s corrupt influence to infiltrate the United States “through channels of exchange and credit.” At their most strident, Republicans charged that the Federalist elite wanted to reinstate in America an English-style monarchy. Federalists countered with their own accusations. They brought sedition charges against journalists such as James Callendar on the grounds that the objective of the Republican press was to effect disunion. They held Republicans accountable for the planned slave uprising, Gabriel’s Rebellion, that Virginia authorities had aborted in the summer of 1800. By talking so recklessly of “liberty and equality,” so the Federalist accusation went, the Republicans had unwittingly emboldened the enslaved artisan Gabriel and his co-conspirators. (In fact, Gabriel had been inspired to think he might succeed by the very rumors of national ruin that overheated partisans on both sides were spreading during the election campaign.) They predicted that if he were elected, Jefferson’s “infidel” regime would undermine American virtue and religion and bring civil war. The resort of politicians and editors to such language fostered a crisis mentality in the electorate. “With partisan animosity soaring and no end in sight,” Joanne Freeman explains, “many assumed that they were engaged in a fight to the death that would destroy the Union.”7

An electoral tie between Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr of New York (who had skillfully built a Republican base to challenge Federalist dominance there), precipitated a constitutional crisis. With the Federalist Congress threatening machinations such as anointing the Federalist president pro tem of the Senate as the successor to Adams, Republicans, led by Governors James Monroe of Virginia and Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania, assumed a disunion posture again, threatening not to accede to any such Federalist “usurpation.” Under the cloud of potential violence—realizing they must “take Mr. Jefferson” or “risk … a civil war,” as one prominent Federalist put it—the House of Representatives finally broke the deadlock in February 1801, and Federalists conceded Jefferson’s victory. Republicans, having successfully used disunion talk as both threat and accusation, would now confront a Federalist opposition eager to perfect that art.8

THE WAR OF 1812

President Jefferson would find the extreme states’ rights vanguard in his own party, the “Tertium Quids” (or “Old Republicans”) led by John Randolph of Roanoke, willing to use intimations of disunion to counter any threat to slavery and to keep the Republican administration honest—loyal to the “principles of ‘98” as embodied in the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions. Randolph personally threatened disunion in 1807 to oppose Northern proposals that the interstate coastal slave trade be restricted even as the African trade was prohibited. Such posturing “could never attract much support in the South,” William Cooper Jr. has written, “so long as southerners perceived governmental power being exercised by a party they identified as their own”; moreover, Randolph himself was a notorious eccentric who would “sometimes appear in Congress booted and spurred, flicking his riding whip.” But the threats were nonetheless more than transparent pressure tactics—for Randolph, together with fellow Virginian John Taylor of Caroline County and Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina, led a group that began to weave from the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions and the Tenth Amendment an intricate philosophy of state sovereignty. The Old Republicans maintained unequivocally that the states were sovereign (indeed, Taylor, the political theorist in the group, called them “state-nations”) and that the Union was a revocable compact, a treaty of sorts, between the states. In other words, the central government—they preferred the term “confederacy” to “nation”—was subordinate to the states. From this political philosophy, Randolph, Taylor, and Macon derived the right of secession: that is, each state could, if the government or other states tried to impose unwanted measures on it, secede, as a sovereign, from the confederacy. While Randolph and the leading Quids lacked an interest in “careful political planning,” as Cooper has put it, they did hope to furnish successive generations of Southerners with a rationale for resisting any encroachment on the “agrarian independence” of the South.9

Randolph and the Old Republicans would have to bide their time, as mainstream Republicans focused during Jefferson’s administration on stigmatizing Federalists as disunionists. Indignant that the Louisiana Purchase would open the way for the expansion of slavery and thus upset the political balance struck by the three-fifths compromise, a cadre of New England Federalists under Massachusetts senator Timothy Pickering explored, in 1803–4, the possibility of forming a New England confederacy and even allying with Quebec and Britain. Although this failed scheme “can hardly be called a plot since it never took concrete form,” as Richard Buel Jr. points out, it nonetheless provided ammunition to Republicans in their campaign to tar their critics with treachery. So, too, did an ill-conceived scheme of Aaron Burr’s: in 1806–7 he attempted to hatch his own “filibuster”—a private military expedition—to seize territory in the Southwest. Although the plan was stillborn, Republicans, who had abandoned and smeared Burr after the 1800 election imbroglio, cannily cast his machinations as profoundly dangerous—a grand conspiracy to destroy the Union—rather than as ineffectual. At this moment, and then again when Federalists objected to Jefferson’s embargo of Britain and to Louisiana’s statehood, Southern Republicans, in the name of nationalism, discredited their opponents as a “factious minority” that was inciting a rebellion against the government.10

Federalists persisted in trying to use disunion arguments to their own partisan advantage. When, under Jefferson’s successor Madison, the economic standoff between the United States and Britain erupted into war in 1812, disaffected New England Federalists charged that Republicans were the tools of the French emperor Napoleon, and that the administration’s purpose was to advance Southern and Western regional interests at the expense of the Northeast. Not only was New England’s commerce undermined, but also its coastline was especially vulnerable to attack from the British military base in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Paradoxically, these New England Federalists did not see their defense of their own regional interests, even their threats of disunion, as sectional in nature, for they clung fiercely to the notion that they embodied the true principles of the Constitution and of the nation itself—that New England’s founders, not Virginia’s, had first planted the tree of liberty on America’s shores.11

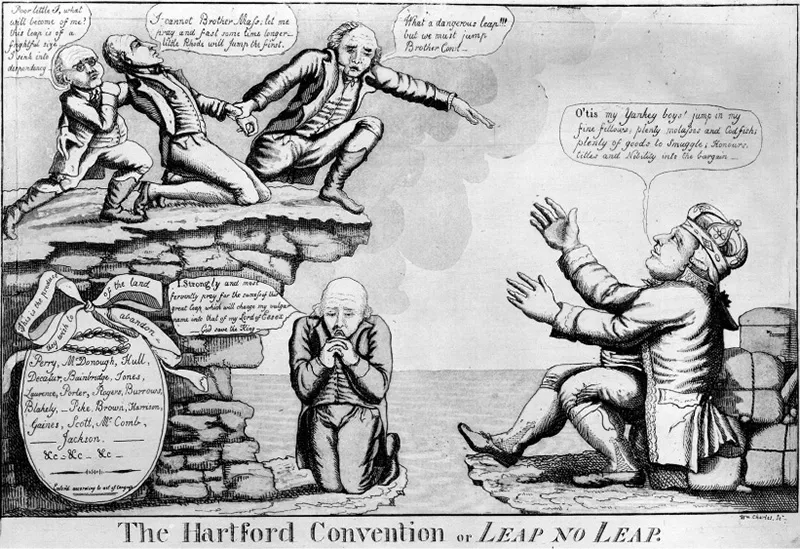

AS FEDERALIST “FIREBRANDS” such as John Lowell Jr. and Harrison Gray Otis of Massachusetts raised anew the possibility of New England’s secession, Republicans in the North and South again counterattacked. Madison’s vice president, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, condemned the dissenters, charging that secession would be calamitous for his state and that the Federalists had fallen prey to “foreign influence.” South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun, discoursing on the difference between legitimate and illegitimate opposition, labeled the Federalist disunion talk as illegitimate—it was a “vicious” attempt to “deliver the country … to the mercy of the enemy.” By the time of the Hartford (Connecticut) Convention in December 1814—a meeting that advertised itself as a constitutional convention of the aggrieved New England states—the dissenters were in retreat. The convention attracted a mere twenty-six delegates from three states who shied away from advocating secession; instead, they proposed constitutional amendments to curtail Congress’s ability to “wage war, regulate commerce, and admit new states.” This program, writes Buel, was “scarcely less subversive” than disunion and left New England Federalists, in the wake of a negotiated peace that ended the war, humiliated and divided. Southern opinion makers such as Thomas Ritchie, editor of the Richmond Enquirer, and even Quid leader John Randolph, delighted in branding the Hartford proposal as treasonous. The Missouri controversy of 1819 would provide the disgruntled Federalists an opportunity, according to Buel, for “refurbishing their morally tarnished credentials.”12

In this pictorial critique of the Hartford Convention, New England Federalists nerve themselves for the “dangerous leap” into the arms of England’s King George III, while Timothy Pickering prays for their success. The image of the precipice soon became a ubiquitous metaphor for conveying the irrationality and self-destructiveness of disunion....