![]()

1 STREET LIFE

The streets of Tangrenbu were vibrant with a curious and colorful mix of Chinese and non-Chinese. Stores that served the residents were interspersed with those that depended on tourists. The fish and poultry markets radiating aromatic and pungent smells, curio-shop bazaars, itinerant peddlers, huge flowered lanterns, gold-red-and-black signs, and so much more—all this served as the interface between the white world that visited and the Chinese world whose home this was. It was on this public turf, the streets, that Arnold Genthe took his photographs. Despite Genthe’s often idealized and romantic notions of the Chinese community his images, while they show us this interface, at the same time manage to carry us beyond the superficial impression of a monolithic Chinese people in a monolithic Chinatown. When these photographs are printed full-frame without retouching, we begin to see the tremendous richness, the variety the nuances of the life of the quarter. Instead of reconfirming what we feel we already know about American Chinatowns, these images challenge us to reconsider stereotypical notions. With the aid of informed historical commentary the photographs come alive, teaching us a lesson in the largely forgotten visual history of Tangrenbu.

For the occasional non-Chinese visitor, the streets of Chinatown were an exotic adventure full of the mystery of the unknown, promising surprises and thrills. The colors, the smells, the language, and the customs seemed so totally foreign to Western sensibilities. Would they see an opium den? What exactly was in the food they were eating? What interesting gifts could they buy for their loved ones? To a large degree the Chinatown that tourists came to see was not the real, everyday quarter, but the quarter as it was fervently imagined by non-Chinese writers, journalists, missionaries, and concerned individuals on both sides of the “Chinese Question.” Tangrenbu was characterized as simultaneously a romantic, melodramatic, wicked, and dangerous place, full of decadence, evil, and disease. Paid guides offered to take the curious to the darkest spots of the quarter. For outsiders, Chinatown was perceived as an escape from the humdrum. It was a quick vacation.

For Chinese residents, however, Tangrenbu, composed of ten blocks of buildings, streets, and narrow alleyways, was at once a living community and a ghetto prison. Chinatown was a home base, a safe place to rest. The rhythm, sounds, colors, and space were comfortable. The streets were full of life where old friends and familiar enemies could be found. The streets offered news, entertainment, gossip, and solace. It was a place to hang out, a place to work, a place to demonstrate deep-felt convictions. Male “bachelor” workers dominated the streets. On special occasions, a wealthy merchant with his family could be seen, and even more rarely the quarter’s few women could be spotted outdoors getting a break from their confined existence behind closed doors. But to venture too far beyond the boundaries of Tangrenbu without official business was to invite harassment and possible injury Wei Bat Liu*, an “old-timer” interviewed by Victor and Brett de Bary Nee in their classic oral history of San Francisco’s Chinatown, Longtime Californ’, recalled:

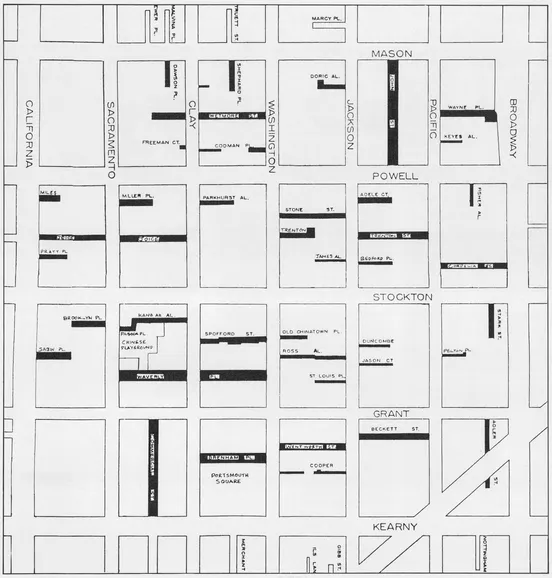

“In those days, the boundaries were from Kearny to Powell, and from California to Broadway. If you ever passed them and went out there, the white kids would throw stones at you. . . . One time I remember going out and one boy started running after me, then a whole gang of others rushed out, too.”1

Gim Chang* also remembered these childhood fears:

“1 myself rarely left Chinatown, only when I had to buy American things downtown. The area around Union Square was a dangerous place for us, you see, especially at nighttime before the quake. Chinese were often attacked by thugs there and all of us had to have a police whistle with us all the time. I was attacked there once on a Sunday night, I think it was about eight P.M. A big thug about six feet tall knocked me down. I remember, I didn’t know what to do to defend myself, because usually the policeman didn’t notice when we blew the whistle. But once we were inside Chinatown, the thugs didn’t bother US.”2

The militant, often violent anti-Chinese movement was still strong at this time. Samuel Gompers, the first president of the American Federation of Labor, spearheaded much of the movement to have Chinese permanently excluded from immigrating to the United States, a movement culminating in the law passed by Congress in 1904. He made fiery speeches claiming the “yellow peril” was still a threat to white working men and women. A pamphlet he coauthored, Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion: Meat us. Rice; American Manhood Against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive?, published in 1902, was widely circulated throughout the country The violence committed against Chinese who ventured outside the borders of Chinatown was not simply the mischievous pranks of misguided “hoodlums” but, far more significantly, one of the several ways in which the dominant powers of the San Francisco community kept the Chinese “in their place.”

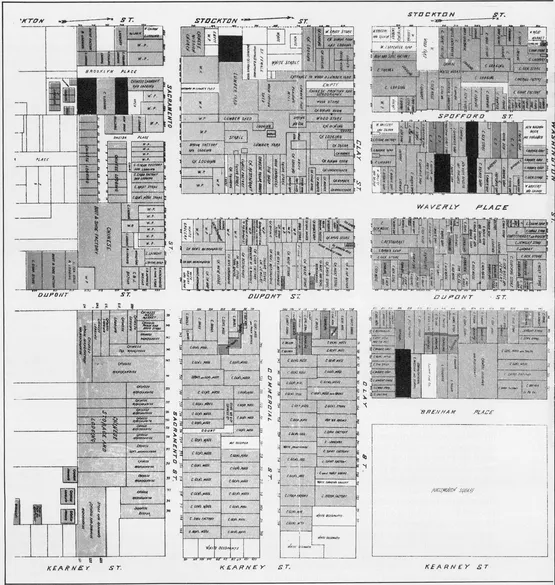

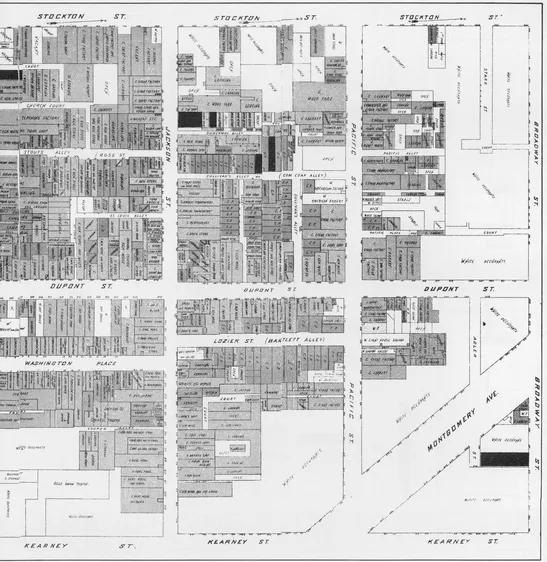

Fig. 3. Map of Old Chinatown. The commercial spine of Chinatown was Dupont Street between California Street (left edge of map) and Broadway (“Broadway St.” on this map). Dupont Street was renamed Grant Avenue after the earthquake, but Chinese residents still call it “Dupont” in Cantonese. The Italian North Beach area and the notorious “Barbary Coast,” with its rowdy seamy night life, bordered the northern edges of Tangrenbu (north is to the right on this map). To the east lay the Hall of Justice, commercial warehouses, and the docks. On the southern border of the quarter, along Sacramento and Dupont Streets, were located white prostitutes and shooting arcades. Above Stockton Street were the posh mansions and hotels of Nob Hill, which overlooked the entire area. (From Willard B. Farwell, The Chinese at Home and Abroad, 1885.)

The brick Italianate buildings and wooden structures that lined the streets of Tangrenbu were inherited from the San Francisco building boom of the 1850s and 1860s. The Chinese, as they came to dominate the area, brought their own sense of space, design, and aesthetics by modifying the buildings and open areas, thereby claiming the quarter as their own. Balconies painted with greens and yellows were added and bedecked with potted plants. Metal and canvas canopies jutted out from storefronts, and lanterns of various shapes and sizes hung everywhere. Within the strictly imposed boundaries space was at a premium. Buildings were constantly modified to make more room. Previously unused basements became stores and residences. Closed wooden constructions projecting from window frames were connected by outdoor stairways and ladders. The rooftops, hung with laundry were here and there divided by picket fences to serve as protection from raiding police or neighborhood feuds.3

Fig. 4. Chinatown today. Based on a 1982 map, courtesy of Chinatown Neighborhood Improvement Resources Center, San Francisco.

In the early morning fog, the markets bristled with activity. Fresh fruits and vegetables were being brought to the produce and other food markets on Dupont and other streets. Fish and poultry were being sold in “Fish Alley.” The many itinerant peddlers in the quarter would be setting up on their favorite doorstep or street corner. Throughout the day, dry goods would be unloaded from the docks and carted up by dollies and horse-drawn wagons along Washington and Clay Streets to their destinations in the general merchandise stores and warehouses on Dupont, Sacramento, Clay, and Commercial Streets. All day long, along the roomier edges of Tangrenbu around lower Clay, Pacific, and Stockton Streets, workers could be seen hunched over their benches in basements and storefront factories making shoes and boots, sewing garments, and assembling brooms. Retired “old-timers” would sit on Portsmouth Square and watch the children with their nannies and mothers. Along Dupont Street, tourists visited the growing number of curio shops that displayed items ranging in price from a few pennies to thousands of dollars. During mealtimes, basement restaurants would be filled with workers having rice and noodle dishes and other inexpensive fare, while merchants would be dining on the floors above.

When darkness came, the clacking of mahjong tiles could be heard behind closed doors, and the alleys were filled with those seeking entertainment and relief from the long day’s work. Ross Alley buzzed with gamblers. Sullivan’s and Bartlett Alleys were busy with lonely men seeking singsong girls and prostitutes. And the theaters on lower Jackson Street and Washington Street off Waverly Place were filled with noisy spectators checking out the development of plays that went on for several nights. Each street had its own special character, different at different times of the day and night.

Waverly Place, for instance, was a two-block-long street nestled in the heart of Tangrenbu. Its Chinese name was Tianhoumiaojie (Tin Hau Miu Gaai), after the Goddess of Heaven, Tianhou, protector of fishermen, travelers, sailors, actors and prostitutes; her temple was erected at 33 Waverly Place (see Plate 12). The street was also given the nickname of “Fifteen Cent Street,” referring to the numerous Chinese barbershops lining the two blocks. The barbershops were open for business when they put out a wash pan placed on a wooden rack outside their door (such a rack is seen next to the two onlookers in Plate 9). The queues the...