![]()

Chapter 1

PERFORMING THE PRESIDENCY: THE IMAGE OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT ON STAGE

Michael Patrick Cullinane

Cultural representations of Theodore Roosevelt have flourished since his death in 1919. Over one hundred motion pictures portrayals exist, from cameos in short and silent films to TR in leading roles, and even TR in animated television sitcoms like The Simpsons. In pop culture, we find Roosevelt in literature, fine art, music and fashion, and his speeches are regularly invoked by politicians, sports stars, celebrities and corporate leaders. Although its impact is largely neglected by scholars and commentators, particularly in comparison to these other mediums, theatre has also played an important role in our perception of Roosevelt. If its capacity to shape historical imagery is generally underestimated, a recent controversy offers ample evidence of its power to do so.

In 2015, the social media campaign Women on 20s pressured the Obama administration to replace Andrew Jackson’s profile on the $20 bill with that of a famous American woman. Shortly after the campaign began, the US Treasury Department announced that it would include more women on greenbacks, but instead of replacing Jackson it reported that Alexander Hamilton would vacate the front of the $10 note.1 Hamilton’s devotees reacted with fury. After all, he was the first person to lead the Treasury Department and founded the very mint that produced American currency. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow said the decision effectively corrected ‘one historic injustice by committing another.’ In the same corner, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke urged the Treasury to reconsider.2 Almost a year after he declared the redesign, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew changed his mind. Hamilton would stay put, and Lew decided that Andrew Jackson would make way for the abolitionist Harriet Tubman on the front of the $20 note. The turnaround owed less to the pressure of the Women on 20s campaign or the disapproval from political heavyweights like Clinton and Bernanke. Hamilton was spared because an eponymous theatre production had set his life to a hip-hop musical.3 Written and produced by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton: The Musical has set box office records, won unequivocal critical acclaim and has brought the story of the Founding Fathers to a new generation by way of contemporary pop culture. Perhaps more than any previous theatre production, Hamilton has demonstrated the power of performing arts for historical image.

Presidential images in film, television, music, art and architecture have an unmistakable effect on our impression of the past.4 As sociologist George Lipsitz put it, culture is ‘not a sideshow.’5 It reflects human experience and communicates popular discourses; it defines shared truths and distinguishes social boundaries. Cultural outputs often demonstrate how the past undergoes dramatic re-conceptualization. In this way, the past never remains static, even if the appearance of a painted portrait or the architecture of a monument endures unchanged over hundreds of years. New audiences consume timeworn cultural outputs differently, and even if the creation of culture begins with the intentions of its author(s), throughout its existence a cultural product belongs to the audience(s) that derive meaning from it. As such, historical images tend to modify according to their context. It is why Hamilton remains on American currency, and why Jackson was scheduled to make way for Tubman. A century from now, that might change – Jackson might reappear and Hamilton might disappear. The past is contested ground, and the battle over historical image plays out in cultural mediums.

When it comes to the American presidency, the place of the chief executive as head of state, head of government and a nationally elected figure generates pervasive public attention. The office attracts countless memorialists who construct myriad images intended to portray the past in ways that have meaning for future generations. Consequently, the image of former presidents encourages periodization, metanarratives and myth. Presidential representations in culture often hasten meme-making. For example, the nineteenth century’s ‘Age of Jackson’ persists in public memory, as does the apparent ‘greatness’ of the four presidents carved on Mount Rushmore.6 Caricatures range from abstract portraits like Jim Shaw’s 2006 ‘Untitled’ tapestry to the ludicrous depictions of Abraham Lincoln as a zombie slayer or a vampire hunter in cinematic portrayals. Not all these images endure and resonate with successive generations, but many do, and each leaves an imprint, no matter how small. Think of the impression made by Lincoln’s immense statue set in a memorial temple on the national mall, or the Lincolniana traded over eBay for thousands of dollars, or Daniel Day-Lewis’s portrayal of the sixteenth president in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. Cultural productions craft our perception of the past in enduring ways. Journalist Jackie Hogan argues that in learning about presidential representations ‘we learn about ourselves, about who we are and who we wish we could be.’7

What distinguishes theatre productions from other cultural outputs is the portrayal of presidents or the presidency through live performance. Theatre literally stages the past, allowing audiences to experience a re-enactment. We might accept that a degree of fiction and dramatization is necessary to theatre, but like the re-enactment of military battles, live acting produces an experiential familiarity with the past, dispossessed of Hollywood special effects and the artistic licence that often accompanies motion pictures. As live spectators, the audience recognizes historical agency, and the performance of the past can ‘leave us with a renewed sense of history as a lived experience of time, of history as becoming.’8 Perhaps more than any other medium, the performing arts challenge our notions of time and historical action, be it the anachronistic hip-hop songs of Hamilton, the deeply researched re-enactments of the American Civil War that bring Confederates ‘out of the attic,’ in spoken word recitals or in abstract acts of expression through dance or display.9 Audiences interact with live actors; performers grapple with how best to depict the past to achieve their impression of historical characters. These unique attributes of theatre have an impact on popular memory and make it a worthy cultural medium to study and to better help us understand presidential image and its representations. And yet, curiously, the performing arts have remained largely overlooked by scholars of the presidency.10

Of course, theatre productions have some significant drawbacks for analysing image. Unpopular or semi-popular productions tend to fade quickly from public consciousness – if they held it at all. In addition, because presidential images have such considerable cache among the public, audiences and critics instinctively consider an actor’s likeness to the president and this can make the theatre ‘more an impersonation than a real drama.’11 Despite these obstacles, hundreds of theatrical representations of the presidency exist, and the theatre offers a rich tableau of our evolving perception.

To further appreciate the impact of theatrical productions on presidential image, this chapter examines four stage representations of the twenty-sixth president, Theodore Roosevelt, from two popular Broadway plays, namely Joseph Kesselring’s Arsenic and Old Lace (1939) and Jerome Alden’s Bully (1977), to an off-Broadway production from The TEAM’s RoosevElvis (2015), and a spoken-word performance from Daniel Mallory Ortberg called ‘Dirtbag Teddy Roosevelt’ (2014). Theatrical performances of these four productions provide a diverse range of representations and show that TR’s image remains deeply contested in this particular art form. This chapter also aims to demonstrate the role of stage writers, actors and producers in shaping different perspectives of Roosevelt’s image and will illustrate how theatre derives inspiration from historical context. The stage, much like film or television, belongs to a moment in which history is performed, but unlike motion pictures, theatre is often re-staged in new venues, with new casts and at times when audiences hold different perspectives. Because of this, performance art provides a unique insight into the evolution of image.

The Most Adolescent of Men

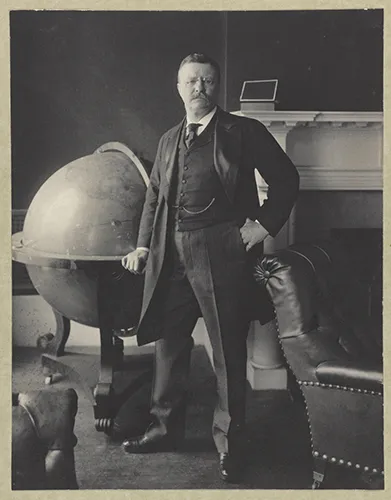

As president, Theodore Roosevelt projected an image of activism on behalf of the national interest both at home and abroad. In his autobiography, he set out what became known as his ‘stewardship theory’ that America’s chief executive had both the right and the duty to do anything the country’s interests required provided he operated within the Constitution and the laws. ‘I acted for the public welfare,’ he declared. ‘I acted for the common well-being of all our people.’ In pursuit of this end, he displayed acute awareness of his symbolic role. Not only did he set the political agenda through speeches and close relations with the media, he also commanded public attention, historian David Greenberg noted, ‘by mastering the tools and techniques of persuasion and image craft that would, decades later, come to be known as spin.’12 Photographs of him were part of this strategy in conveying a sense of his gravitas, command and competence to do what was right for the country (see below). Though successful in promoting this self-image during his presidency, it did not long survive his early death at the age of sixty in January 1919. Theatre would play its part in the debunking of the image that the twenty-sixth president had so assiduously developed during his tenure in office.

Figure 1.1 Theodore Roosevelt projects confidence in America and himself in a 1908 photograph. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-36041, unrestricted use.

In 1931, journalist Henry Fowles Pringle published the first revisionist biography of Theodore Roosevelt. Pringle cut his teeth as an investigative reporter in New York before turning his hand to biography writing. He drew inspiration from a school of political critics known as debunkers who aimed to revise the portraits of political idols. Roosevelt was ripe for such revision. Biographies that had hitherto appeared since Roosevelt’s death, mostly written by individuals who had known him, emphasized his greatness and his goodness. Pringle’s book cast off the portrait of a saintly, high-minded character and transformed public perception by rendering the president a juvenile delinquent and reckless demagogue. In his telling, Roosevelt’s trust-busting and government regulations became the product of an insufferable ego. Pringle presented Roosevelt’s domestic policies as narcissistic, and his foreign policies as eager interventions designed to extend presidential power. The arbitration of the Russo-Japanese War, according to Pringle, was ‘gratifying, but much less enjoyable’ than the charge up San Juan Heights in the Spanish-American War.13

Until Pringle, no biographer had so obviously tipped the scales of Roosevelt’s popular memory against him. In fact, the image of an adolescent Roosevelt was so convincing that few new biographies appeared in the 1930s or 1940s, and none challenged Pringle’s revisionist narrative. What made Pringle’s reversal of Roosevelt’s saintly image so credible and compelling was the vast archival research on which he based his portrait. Consequently, historians for more than a generation hailed Pringle’s biography as a ‘first-rate contribution’ of ‘scholarly thoroughness, judgment, and detachment.’14 Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1932, his ‘crazy Teddy’ portrait established itself as TR’s standard image.15

A debunked Roosevelt did not escape self-parody. Pringle constructed an image by overemphasizing a single character trait: adolescence. On nearly every page, the biographer refers to Roosevelt’s ‘juvenile’ personality, most zealously in the years surrounding the War of 1898. For Pringle, Roosevelt’s service in the Rough Riders was defined by childish exuberance. His young adulthood and the pre-presidential years became a whirl of frenzied, impulsive and infantile moments defined as a psychological overcompensation for personal demons, such as his asthma and his father’s failure to serve in the Civil War. When...