![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to criminal law

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Understand why the criminal law exists

- Demonstrate a basic understanding of the principles

- Understand how and where a criminal prosecution is begun

- Have some understanding of the court process

The most appropriate starting point in a book on criminal law is to consider what a crime is. Simply defined, a crime is a public wrong, one that adversely affects society as a whole. It is an act that so offends society’s standards of acceptable behaviour that it is appropriate to punish the offender rather than to compensate the aggrieved party. This chapter provides the reader who has no previous understanding of the criminal law to understand basic principles relating to what amounts to a crime, the elements of a criminal offence, sentencing and a brief introduction to the court process. Subsequent chapters discuss more substantive offences as well as defences and the subject areas identified are those that most undergraduate and postgraduates courses teach. Students should always remember that many of the areas interconnect. For example, you may be required to consider the offence of murder and the defence of self defence in a single exam question. We begin by considering the more philosophical approach to the criminal law.

Causing Harm to Others

John Stuart Mill, the English philosopher (On Liberty and other writings (1859) ) explained that actions of individuals should not be restricted by society except where it is necessary to prevent harm being inflicted on others.

The only purpose for which power can rightfully be exercised over any member of a civilised society against his will, is to prevent harm to others.

Mill explains that society should not interfere with another person’s free choice unless that person’s behaviour harms society.

There is little doubt we agree that the State should intervene to protect us when harm is caused but what is harm? Is harm caused to the individual or to society as a whole? Arguably, the two appear linked, if harm is caused to an individual, then society suffers as well. Harm has to be such that it threatens the mere fabric of society. Restricting harm caused to the individual protects not only the individual but invariably protects society – therefore an individual’s restriction of behaviour can be justified where the greater good is concerned.

It is for society to determine what constitutes ‘harm’. In a democratic society this should pose little difficulty. We all accept murder, rape, manslaughter, robbery, burglary and theft are all acts which are clearly wrong. Here, the victim should be protected from the ‘wrong’ and the wrongdoer should be punished. However, even here morals (which we look at shortly) play a role. For example, we all agree theft is wrong; harm is caused if I steal a wallet from the person sitting next to me on the train. Harm is caused to the individual and society needs to be protected from my actions! Compare my act to the single unemployed mum who steals a pint of milk and a loaf of bread to feed her family. Is harm caused here? Is her act equally as reprehensible as mine? We all know one should not steal but does society really need protection from her? Arguably not. Although the quality of the act is the same the motives are very different. Although motives play no role in criminal law, this simple example shows there are varying differing standards as to what amounts to an act that causes harm. Not only is this dependent on the morals of those who represent our ‘society’ but it is also largely dependent on society’s expectations and the changing values of that society.

Morality

So far we have seen that ‘harm’ is a difficult concept to attempt to define. There is little doubt that morality plays a significant part in the development of the criminal law. Again, morality is a tricky term to define and it is often guided by the standards of the particular culture one studies. For example, female genital circumcision is an accepted practice in parts of Africa, most commonly in Northern Eastern parts, but here in the UK it is morally unacceptable and now, since the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003, unlawful.

The law in England and Wales permits us to consent to a certain level of self-harm (see Chapter 7), for example, we can consent to tattooing and all forms of exotic body piercing even though we may not all find it attractive, or even acceptable.

However, there are areas of harm where the law has intervened and the case below illustrates how the law can impose its moral stamp of authority.

Contrast Brown with Wilson below.

What is the real difference between the cases? In Wilson injury was caused (albeit minor) and Mrs Wilson required medical attention. No such injury was caused in Brown. Brown involved activities which involve sexual gratification; in contrast, Mr Wilson did not receive any sexual gratification. In reality, Brown is a judgment where morals were examined and statements made as to how people should behave. The activities of a minority group of people with a tendency to alternative sexual acts were not the kind of activities that the court concluded could be either accepted as ‘normal’ or acceptable and hence they were criminalised.

The judgment’s principle is reflected by Sir Patrick Devlin in The Enforcement of Morals as he explains:

The criminal law is not a statement of how people ought to behave; it is a statement of what can happen to them if they do not behave; good citizens are not expected to come within reach of it or to set their sights by it, and every enactment should be framed accordingly.

What is Punishment and Why Do We Have It?

One of the interesting aspects of a study of the criminal law, in contrast with other areas of law, is that the criminal law seems almost tangible. Turn on the television and there will invariably be a drama, news item or media portrayal of some offence being committed. The same applies to punishment. Sometimes we might even consider that punishment of criminal offences is glamorised by the media.

In contrast to the civil law, where compensation between the parties is sufficient, a victim of a criminal offence might, quite rightly, be offended if the State suggested that compensation was an adequate remedy between the parties.

The State punishes the wrongdoer in order to enforce boundaries of acceptable behaviour. It is also a form of ‘retributive justice’ where the offender must face the consequences of his undesirable activities. Retribution was one of the main principles behind the Conservative Government’s reform of sentencing: Crime, Justice and Protecting the Public (1990).

Punishment is a form of deterrent which allows others to appreciate the consequences of their potential actions through the punishment of others. A custodial sentence is the ultimate deterrent, reserved for offences where a period of imprisonment and deprivation of liberty satisfies the State that justice is seen to be done.

Punishment also seeks to rehabilitate, reform and re-educate the offender in the hope they will not re-offend. In the situation of a relatively minor drug offence, for example, sentencing the defendant to community service together with attendance at a drug rehabilitation unit (if he shows a desire to rid the habit) could be an effective tool. The aim is to rehabilitate the offender, together with some form of punishment for the offence committed. However, rehabilitation is often difficult to achieve with re-offending rates particularly high. Where an offender is released from a short custodial sentence of under 12 months, the rate of re-offending can, according to the Ministry of Justice, Compendium of Reoffending Statistics and Analysis May 2011, be as high as 70 per cent. The rate is lower for sentences of between two and four years, where the offender has been given a greater opportunity to rehabilitate. Those who re-offend cite a lack of a place to live and unemployment as the main reasons for re-offending.

The State must also consider protecting the public where sentencing is concerned. Whilst originally this may have been achieved by the death penalty, modern-day protection is achieved by imposing lengthy prison sentences. If the offender is not in custody, electronic tagging can restrict an offender’s movements whilst, at the same time, protecting the public by prohibiting the offender from visiting a particular area between certain times. Sometimes the offender is forbidden to visit particular areas, especially if the area is connected with the original offence. The benefit of electronic tagging is that it is less costly than caring for an offender in custody, but at the same time it acts as a deterrent because if the defendant breaches the conditions of his tagging he can be imprisoned for the breach.

The Human Rights Act 1998 – the Act incorporates the provisions of the European Convention of Human Rights into domestic law with effect from October 2000. By virtue of s 6, the onus is on public authorities (for example, the courts, prisons and the police) to ensure that all legislation is compatible, as far as possible, with the Convention rights. Save for the case of Lambert [2002] QB 112, which concerned the reverse burden of proof and the use of Article 6, it would be reasonable to say that terrorism offences (more so than other offences we deal with in this book) have most frequently engaged use of the Convention rights.

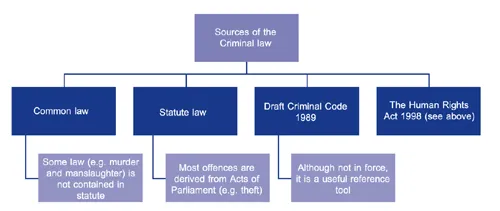

Figure 1.1 Sources of the criminal law

Elements of Criminal Liability

Criminal liability is traditionally expressed in the following Latin maxim ‘actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea’ which can be translated as ‘an act does not make a man guilty of a crime unless his mind is also guilty’.

We examine these terms in detail in Chapters 2 and 3, and here we simply need to outline the basic elements. Most criminal offences require both a guilty act (actus reus) and a guilty mind (...