![]()

1

The Political Organizer

Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 Campaign

Michael S. Green

“Seward will be first on the ballot, Chase next—then Bates or Cameron…. My policy has been to keep down my name everywhere as a candidate for the first office…. Seward’s friends generally prefer me after himself,” and “I think without doubt Chase’s friends will go for me after himself.” This was the optimistic analysis of the 1860 Republican convention that one of the presidential candidates, Cassius Marcellus Clay, a Kentucky abolitionist, shared with Caleb B. Smith, a longtime Indiana Whig who had become a far more conservative Republican than Clay would ever be. Clay was hopeful, as most candidates tend to be, and more so than he had reason to be. Given their desire to carry border slave states and appeal to moderates and conservatives, Republicans would gain little support by nominating a candidate who was radically antislavery. But Clay’s strategy for winning the Republican presidential nomination made sense. Indeed, it worked perfectly—for Abraham Lincoln.1

Like almost every aspect of his life, how Lincoln won the nomination and then the presidency has been the subject of analysis, myth, and debate. One of the problems with understanding his role in the 1860 election lies in the history of his story. Because he was, as his law partner William Herndon observed, “the most secretive—reticent—shut-mouthed man that ever existed,” much about him remains shrouded in mystery: his existing correspondence is limited, and he controlled how much he revealed to those around him. That has freed us to see Lincoln as we wish: as the self-made man, the Great Emancipator, the working man, “Honest Abe,” and even as the humorous yet melancholy man who becomes a martyr to a higher cause.2

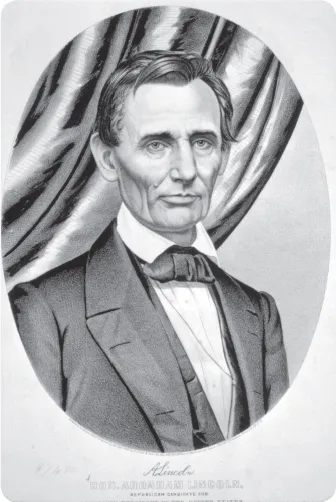

Fig. 2. Hon. Abraham Lincoln: Republican candidate for sixteenth president of the United States. (Library of Congress)

At times, those images diverge from the many examples of Lincoln as the crafty backwoods-turned-urban but never entirely urbane lawyer. Yet many of us prefer not to replace one word that too many associate with evil—lawyer—with another similarly and wrongly abused word involving trickery: politician. If the law became Lincoln’s occupation, politics always remained his preoccupation, from organizing Whigs for campaigns every other year to nearly fighting a duel with a Democratic opponent over an exchange in the press. That preoccupation with politics was evident when he sought the presidency. In 1860, many deserved credit for the political organization and plotting that made Lincoln the nominee and likely victor, but none deserved more credit than Lincoln.3

The views of two Lincoln biographers, divergent in their approaches and times but deeply connected, are important to understanding why he deserved the credit—and, perhaps, why he has received less of it than he should. One is by William Herndon, who referred to Lincoln’s ambition as “a little engine that knew no rest.” The other is by David Herbert Donald, who published biographies of Herndon and Lincoln nearly half a century apart.4 Both of these authors focused on a crucial aspect of Lincoln’s life and personality: his friendships, how he dealt with others. “Those who knew him best came to realize that behind the mask of affability, behind the façade of his endless humorous anecdotes, Lincoln maintained an inviolable reserve,” Donald wrote. Yet he also echoed Herndon’s point, which suffered from what Donald called “only a little exaggeration,” that “no man ever had an easier time of it in his early days—in … his young struggles than Lincoln had. He always had influential and financial friends to help him; they almost fought each other for the privilege of assisting Lincoln.” And so it remained for much of Lincoln’s life, at least in Illinois, until he won a job that placed him above all of those old friends. Many seemed to consider themselves his close friends when they were not. At times they seemed divided mainly over which of them loved Lincoln more or could accomplish more for him. How he dealt with these friends, close friends, and acquaintances—the temptation is to say that he handled them, and that word may be more appropriate—proved crucial to his political future.5

Donald and Herndon described the same man in ways that are not mutually exclusive but part of the same mosaic. Although historians increasingly have accepted the information that Herndon obtained in the process of trying to write Lincoln’s biography, they always have doubted his attempts to interpret Lincoln’s mind. But Herndon certainly knew and understood Lincoln well enough to characterize his ambition and the benefits he derived from friends who wanted to help him. As Donald demonstrated, Lincoln had a capacity for or interest in maintaining truly close friendships only with a select few. Although he could work with a diverse group and benefited from their help, he also was and had to be self-contained and self-reliant in many aspects of his life, especially politics.

With all of the help that he received from friends, Lincoln fitted Richard Hofstadter’s ironic analysis of him as representative of “the self-made myth.” More Lincoln scholars should view Hofstadter’s observation, “The first author of the Lincoln legend and the greatest of the Lincoln dramatists was Lincoln himself,” in the broadest sense. Early in life, Lincoln harbored hopes of escaping what seemed to be his fate of following in his father Thomas’s footsteps as a yeoman farmer. Living in New Salem from 1831 to 1837 and after that in Springfield, Lincoln benefited from community support—thus the importance of his friendships—but he also exhibited a drive to succeed. He tried several professions in New Salem and embarked on a quest for self-improvement that never really stopped, if overcoming his lack of a formal education to become an attorney and the pride he expressed at learning Euclidean geometry while in his forties are any indication.6

Clearly, though, Lincoln found another avenue to advancing himself: politics. Not only did he learn, study, and think about candidates and issues but he also involved himself in a political party. Lincoln was not a joiner: the social clubs that attracted many attorneys and the would-be socially mobile appear to have held little charm for him. He enjoyed the camaraderie of his fellow lawyers on the circuit. In terms of belonging to a group, though, his political party mattered a great deal to him, and that required him to think of both his own ambitions and the greater good of his organization. Thus, he was willing to support candidates such as William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor against his political hero, Henry Clay, for the presidency and was unwilling to break with the Whig party over slavery during the 1840s. His experience in political parties would prove valuable when he sought the presidential nomination in 1860.

Lincoln famously lacked national office-holding experience—after all, he had spent one undistinguished term in the House of Representatives and lost two Senate races in the five years before the 1860 convention. But he had a distinct advantage over his competitors: none of the three main front-runners for the nomination had the breadth or depth of his experience in organizing campaigns for elective office. One of the Republican Party’s leading radical voices, William Henry Seward, served two terms as governor and two terms as a U.S. senator from New York. Although Seward was an excellent backroom operator in the Senate and convivial in his personal relations, no one doubted that he left the details of political management to his close friend and ally, Thurlow Weed. The editor of the Albany Evening Journal, Weed served as a Whig and then as a Republican boss. Seward reportedly declared, “Seward is Weed and Weed is Seward. What I do Weed approves. What he says, I endorse. We are one.” That was not entirely true: Seward’s determined opposition to slavery sometimes vexed Weed politically and ideologically. But the freedom that Seward enjoyed from day-to-day political operations also left him more naïve than his Illinois counterpart about the scutwork of politics and left him open to criticism when Weed’s lobbying and investments raised questions about his probity.7

Salmon P. Chase and Edward Bates reflected opposite ends of the spectrum. Even more radically antislavery than Seward, Chase ran his own campaigns and found it difficult to confide in anyone, but his deal making and sanctimony won him far more enemies than lasting alliances. Nor did he ever dedicate himself to a political party as Lincoln did first with the Whigs and then with the Republicans. He dedicated himself to the cause, antislavery. He saw whatever he did that he benefited from politically as part of a higher calling. Although his actions enabled him to become Ohio’s governor and U.S. senator, they also generated the kind of attitude unlikely to make it easy for him to win over those who doubted his efficacy as a candidate. The barely antislavery Bates avoided the damage that Seward and Chase suffered by refraining from political activity, but that merit also proved to be a demerit: Bates ended up with little political experience of any kind and few significant allies in the Republican rank and file, especially because the Republican Party in Missouri was limited in size and scope. Led by the unusual Republican tandem of Francis Preston Blair, a longtime Democratic operative and Andrew Jackson confidante, and Horace Greeley, the reformist editor of the New York Tribune and onetime Whig, Bates’s supporters resorted to arguing, “We frankly admit that Judge Bates has not long been distinctively a Republican: how many of us have been? We are a young party, rising gradually from nothing to ascendancy: such parties, when destined to succeed, are always liberal toward accessions and careless of antecedents.” That might not have been a problem if Bates had been active enough politically to build a network or a sense of good will, but instead he had little political credit on which to draw.8

In contrast to Bates, Lincoln dedicated most of his adult life to politics—not just thinking deeply about what he believed and why but also the important electoral tasks of campaigning and dealing with the day-to-day drudgery of organizing parties and campaigns. Soon after arriving in New Salem in 1832 at the age of twenty-three, Lincoln sought a legislative seat, and although he lost, he won 277 of the 300 votes in his new community—a sign that he had made himself known to local voters, who found him appealing. In 1834, he tried again and won, partly through cunning that involved the slate of candidates from which voters would choose several legislators. First, with New Salem solidly for Henry Clay’s “American System” of internal improvements and farmers in the hinterland strongly Jacksonian, Lincoln avoided repeating any of his pro-Clay comments from 1832. Second, he agreed to a Democratic plan to funnel votes to him and thereby siphon votes from the presumed front-runner, his future law partner, John Todd Stuart, who encouraged him to take the deal. The Democratic plan worked far less well than Stuart’s and Lincoln’s: Lincoln drew enough votes to win, but so did Stuart. This campaign marked Lincoln’s first lesson in—and foray into—political deal making and organizing.9

As a legislator and Whig, Lincoln worked from the minority, and his success demonstrated his growing political acumen. In addition to his legislative achievements—most notably, perpetuating Whig economic policies and shifting the state capital to Springfield—Lincoln made a name for himself in putting together his party’s campaigns and seeking to broaden his party’s reach. The Whigs suffered from two image problems that contained considerable truth. First, many thought them moralizers who saw themselves as above petty political activity. Second, they were seen as an elite, especially in comparison with the Democrats, whose name seemed to fit them with both a small “d” and a capital “D.” Lincoln looked beyond businessmen and evangelicals, the groups to which Whigs most appealed, toward a larger constituency. He hoped to convince new voters of the benefits of his party’s pro-business proclivities (He even suffered in his efforts when he married Mary Todd, who came from a higher social class than he.) He hoped to win the 7th Congressional District—the only Whig district in Illinois—and engaged in protracted negotiating and behind-the-scenes maneuvering with other Whigs to ensure that they supported both his campaign and rotating the job among party members so that he would have his chance. He put his organizational skills to work on local and national campaigns, including in 1840, when he drew up what David Herbert Donald called “a semimilitary plan for getting out the Whig votes” that included local and county party workers who would ensure “that every Whig can be brought to the polls.” He made similar efforts in 1844 and resented the antislavery Liberty Party and the staunchly antislavery Whigs for declining to support Clay’s election that year.10

Lincoln entered Congress as a little-known party regular, but though his term was short, he made as much of it as he could. His most famous legislative action was a failed attempt to end slavery in the District of Columbia, and how he went about it demonstrated both his desire to unify his often divided party and his preference for seeking a consensus. He also campaigned in New England and again put party fealty above ideology when he backed the nomination of Zachary Taylor over Clay because he realized that the general had a better chance of winning.

Although the end of Lincoln’s congressional term in 1849 prompted a five-year hiatus from his pursuit of elective office, he proved more active in party plotting and organization during this period than he appeared. He advised Whig candidates seeking office through elections and patronage. He delivered eulogies in 1850 for Taylor and in 1852 for Clay—duties that someone less political minded might have ceded to a Whig office seeker. These two eulogies revealed something of Lincoln as a coalition-building politician. His account of Taylor played down the divisions that “Old Rough and Ready”’s presidency had both highlighted and created within the party, especially his opposition to the Compromise of 1850. Having already established a record of disliking slavery, Lincoln certainly could have discussed that issue in some detail but chose not to do so, perhaps because his feelings were mixed on the subject. His eulogy for Clay said less about his American System of internal improvements, w...