![]()

1

Emmeline Pankhurst

British suffragette

Emmeline Pankhurst née Goulden (1857–1928) was one of the significant voices of the women’s suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th century. She fought for women’s suffrage with tenacity and extreme militancy, and was later joined by her daughters Christabel (1880–1958) and Sylvia (1882–1960). Her 40-year-campaign reached a peak of success shortly before her death, when the Representation of the People Act was finally passed (1928), establishing voting equality for men and women.

‘The laws that men have made’

24 March 1908, London, England

Formed in 1887 from 17 separate groups, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies had campaigned persistently but unsuccessfully to gain the vote for women. A growing sense of frustration drove Emmeline and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst to form breakaway groups: the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903 and the more militant Women’s Freedom League in 1907.

Tactics pursued by members of these organizations included heckling political speeches and provoking the police to arrest them for disturbing the peace. Their activities attracted the desired attention, though they were also delightedly lampooned by cartoonists and mainstream newspapers. In 1907, the law was changed to allow women ratepayers to vote in local elections – but this did not satisfy Pankhurst.

In 1908, she gave a series of lectures under the umbrella title The Importance of the Vote. This one was given in the Portman Rooms during the Putney by-election of that year, which added urgency to its message. In her bald but patiently reasoned attack on the status quo, Pankhurst recites men’s legislative shortcomings, condemning them for their failure to improve ordinary women’s lives.

What I am going to say to you tonight is not new. It is what we have been saying at every street corner, at every by-election during the last 18 months. It is perfectly well known to many members of my audience, but they will not mind if I repeat, for the benefit of those who are here for the first time tonight, those arguments and illustrations with which many of us are so very familiar.

In the first place, it is important that women should have the vote in order that in the government of the country the women’s point of view should be put forward.

It is important for women that in any legislation that affects women equally with men, those who make the laws should be responsible to women, in order that they may be forced to consult women and learn women’s views when they are contemplating the making or the altering of laws.

Very little has been done by legislation for women for many years – for obvious reasons. More and more of the time of Members of Parliament is occupied by the claims which are made on behalf of the people who are organized in various ways in order to promote the interests of their industrial organizations or their political or social organizations. So the Member of Parliament, if he does dimly realize that women have needs, has no time to attend to them, no time to give to the consideration of those needs. His time is fully taken up by attending to the needs of the people who have sent him to Parliament.

While a great deal has been done, and a great deal more has been talked about for the benefit of the workers who have votes, yet so far as women are concerned, legislation relating to them has been practically at a standstill. Yet it is not because women have no need, or because their need is not very urgent. There are many laws on the statute-book today which are admittedly out of date, and call for reformation; laws which inflict very grave injustices on women. I want to call the attention of women who are here tonight to a few acts on the statute-book which press very hardly and very injuriously on women.

Men politicians are in the habit of talking to women as if there were no laws that affect women. ‘The fact is,’ they say, ‘the home is the place for women. Their interests are the rearing and training of children. These are the things that interest women. Politics have nothing to do with these things, and therefore politics do not concern women.’ Yet the laws decide how women are to live in marriage, how their children are to be trained and educated, and what the future of their children is to be. All that is decided by act of Parliament. Let us take a few of these laws, and see what there is to say about them from the women’s point of view.

First of all, let us take the marriage laws. They are made by men for women. Let us consider whether they are equal, whether they are just, whether they are wise. What security of maintenance has the married woman? Many a married woman, having given up her economic independence in order to marry, how is she compensated for that loss? What security does she get in that marriage for which she gave up economic independence? Take the case of a woman who has been earning a good income. She is told that she ought to give up her employment when she becomes a wife and a mother. What does she get in return?

All that a married man is obliged by law to do for his wife is to provide for her shelter of some kind, food of some kind and clothing of some kind. It is left to his good pleasure to decide what the shelter shall be, what the food shall be, what the clothing shall be. It is left to him to decide what money shall be spent on the home, and how it shall be spent; the wife has no voice legally in deciding any of these things. She has no legal claim upon any definite portion of his income. If he is a good man, a conscientious man, he does the right thing. If he is not, if he chooses almost to starve his wife, she has no remedy. What he thinks sufficient is what she has to be content with.

I quite agree, in all these illustrations, that the majority of men are considerably better than the law compels them to be…but since there are some bad men, some unjust men, don’t you agree with me that the law ought to be altered so that those men could be dealt with?

Take what happens to the woman if her husband dies and leaves her a widow, sometimes with little children. If a man is so insensible to his duties as a husband and father when he makes his will, as to leave all his property away from his wife and children, the law allows him to do it. That will is a valid one. So you see that the married woman’s position is not a secure one. It depends entirely on her getting a good ticket in the lottery. If she has a good husband, well and good: if she has a bad one, she has to suffer, and she has no remedy. That is her position as a wife, and it is far from satisfactory.

Now let us look at her position if she has been very unfortunate in marriage, so unfortunate as to get a bad husband, an immoral husband, a vicious husband, a husband unfit to be the father of little children. We turn to the divorce court. How is she to get rid of such a man? If a man has got married to a bad wife, and he wants to get rid of her, he has but to prove against her one act of infidelity. But if a woman who is married to a vicious husband wants to get rid of him, not one act nor a thousand acts of infidelity entitle her to a divorce. She must prove either bigamy, desertion or gross cruelty, in addition to immorality, before she can get rid of that man.

Let us consider her position as a mother. We have repeated this so often at our meetings that I think the echo of what we have said must have reached many.

By English law, no married woman exists as the mother of the child she brings into the world. In the eyes of the law she is not the parent of her child.

The child, according to our marriage laws, has only one parent who can decide the future of the child, who can decide where it shall live, how it shall live, how much shall be spent upon it, how it shall be educated and what religion it shall profess. That parent is the father.

These are examples of some of the laws that men have made, laws that concern women. I ask you, if women had had the vote, should we have had such laws? If women had had the vote, as men have the vote, we should have had equal laws. We should have had equal laws for divorce, and the law would have said that as nature has given to children two parents, so the law should recognize that they have two parents.

I have spoken to you about the position of the married woman who does not exist legally as a parent, the parent of her own child. In marriage, children have one parent. Out of marriage children have also one parent. That parent is the mother – the unfortunate mother. She alone is responsible for the future of her child; she alone is punished if her child is neglected and suffers from neglect.

But let me give you one illustration. I was in Herefordshire during the by-election. While I was there, an unmarried mother was brought before the bench of magistrates, charged with having neglected her illegitimate child. She was a domestic servant, and had put the child out to nurse. The magistrates – there were colonels and landowners on that bench – did not ask what wages the mother got; they did not ask who the father was or whether he contributed to the support of the child. They sent that woman to prison for three months for having neglected her child.

I ask you women here tonight: if women had had some share in the making of laws, don’t you think they would have found a way of making all fathers of such children equally responsible with the mothers for the welfare of those children?

…The man voter and the man legislator see the man’s needs first, and do not see the woman’s needs. And so it will be until women get the vote.

It is well to remember that, in view of what we have been told of what is the value of women’s influence. Woman’s influence is only effective when men want to do the thing that her influence is supporting.

Now let us look a little to the future. If it ever was important for women to have the vote, it is ten times more important today, because you cannot take up a newspaper, you cannot go to a conference, you cannot even go to church, without hearing a great deal of talk about social reform and a demand for social legislation. Of course, it is obvious that that kind of legislation – and the Liberal government tell us that if they remain in office long enough we are going to have a great deal of it – is of vital importance to women.

If we have the right kind of social legislation it will be a very good thing for women and children. If we have the wrong kind of social legislation, we may have the worst kind of tyranny that women have ever known since the world began. We are hearing about legislation to decide what kind of homes people are to live in. That surely is a question for women. Surely every woman, when she seriously thinks about it, will wonder how men by themselves can have the audacity to think that they can say what homes ought to be without consulting women.

Then take education. Since 1870 men have been trying to find out how to educate children.1 I think they have not yet realized that if they are ever to find out how to educate children, they will have to take women into their confidence, and try to learn from women some of those lessons that the long experience of ages has taught to them. One cannot wonder that whole sessions of Parliament should be wasted on education bills…

The more one thinks about the importance of the vote for women, the more one realizes how vital it is. We are finding out new reasons for the vote, new needs for the vote every day in carrying on our agitation.

I hope that there may be a few men and women here who will go away determined at least to give this question more consideration than they have in the past. They will see that we women, who are doing so much to get the vote, want it because we realize how much good we can do with it when we have got it. We do not want it in order to boast of how much we have got. We do not want it because we want to imitate men or to be like men. We want it because without it we cannot do that work which it is necessary and right and proper that every man and woman should be ready and willing to undertake in the interests of the community of which they form a part.

![]()

2

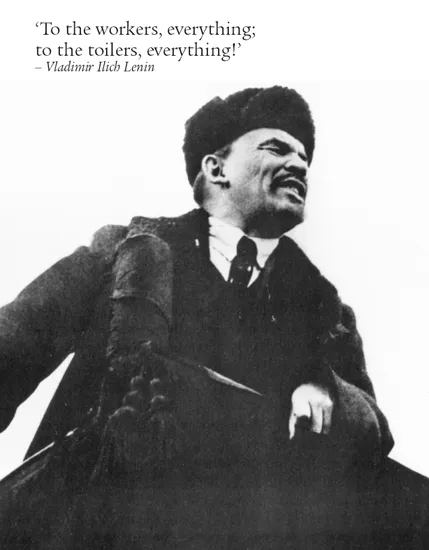

Vladimir Ilich Lenin

Russian revolutionary leader

Shrewd, dynamic, pedantic and implacable, the Marxist political activist Vladimir Ilich Lenin (1870–1924) spearheaded the October Revolution of 1917 and inaugurated the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ that was to rule Russia for more than seven decades. Despite the ultimate failure of Soviet communism, his influence endures in Russia and beyond.

‘To the workers, everything; to the toilers, everything!’

30 August 1918, Moscow, Russia

The occasion of this speech was a mass meeting in the hand-grenade shop of Moscow’s Michelson Factory.

Much had changed in Russia after the February Revolution (in March 1917, by modern dating), which had forced Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication and established a provisional government of moderate reformists. Although Lenin – unwilling to compromise his careful plans to reorganize the government and economy – had not taken advantage of anti-government demonstrations in July 1917, he had led the successful Octo...