Energy Geostructures

Innovation in Underground Engineering

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Energy Geostructures

Innovation in Underground Engineering

About this book

Energy geostructures are a tremendous innovation in the field of foundation engineering and are spreading rapidly throughout the world. They allow the procurement of a renewable and clean source of energy which can be used for heating and cooling buildings. This technology couples the structural role of geostructures with the energy supply, using the principle of shallow geothermal energy. This book provides a sound basis in the challenging area of energy geostructures.

The objective of this book is to supply the reader with an exhaustive overview on the most up-to-date and available knowledge of these structures. It details the procedures that are currently being applied in the regions where geostructures are being implemented. The book is divided into three parts, each of which is divided into chapters, and is written by the brightest engineers and researchers in the field. After an introduction to the technology as well as to the main effects induced by temperature variation on the geostructures, Part 1 is devoted to the physical modeling of energy geostructures, including in situ investigations, centrifuge testing and small-scale experiments. The second part includes numerical simulation results of energy piles, tunnels and bridge foundations, while also considering the implementation of such structures in different climatic areas. The final part concerns practical engineering aspects, from the delivery of energy geostructures through the development of design tools for their geotechnical dimensioning. The book concludes with a real case study.

Contents

Part 1. Physical Modeling of Energy Piles at Different Scales

1. Soil Response under Thermomechanical Conditions Imposed by Energy Geostructures, Alice Di Donna and Lyesse Laloui.

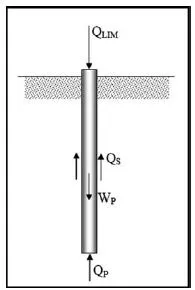

2. Full-scale In Situ Testing of Energy Piles, Thomas Mimouni and Lyesse Laloui.

3. Observed Response of Energy Geostructures, Peter Bourne-Webb.

4. Behavior of Heat-Exchanger Piles from Physical Modeling, Anh Minh Tang, Jean-Michel Pereira, Ghazi Hassen and Neda Yavari.

5. Centrifuge Modeling of Energy Foundations, John S. McCartney.

Part 2. Numerical Modeling of Energy Geostructures

6. Alternative Uses of Heat-Exchanger Geostructures, Fabrice Dupray, Thomas Mimouni and Lyesse Laloui.

7. Numerical Analysis of the Bearing Capacity of Thermoactive Piles Under Cyclic Axial Loading, Maria E. Suryatriyastuti, Hussein Mroueh, Sébastien Burlon and Julien Habert.

8. Energy Geostructures in Unsaturated Soils, John S. McCartney, Charles J.R. Coccia, Nahed Alsherif and Melissa A. Stewart.

9. Energy Geostructures in Cooling-Dominated Climates, Ghassan Anis Akrouch, Marcelo Sanchez and Jean-Louis Briaud.

10. Impact of Transient Heat Diffusion of a Thermoactive Pile on the Surrounding Soil, Maria E. Suryatriyastuti, Hussein Mroueh and Sébastien Burlon.

11. Ground-Source Bridge Deck De-icing Systems Using Energy Foundations, C. Guney Olgun and G. Allen Bowers.

Part 3. Engineering Practice

12. Delivery of Energy Geostructures, Peter Bourne-Webb with contributions from Tony Amis,

Jean-Baptiste Bernard, Wolf Friedemann, Nico Von Der Hude, Norbert Pralle, Veli Matti Uotinen and Bernhard Widerin.

13. Thermo-Pile: A Numerical Tool for the Design of Energy Piles, Thomas Mimouni and Lyesse Laloui.

14. A Case Study: The Dock Midfield of Zurich Airport, Daniel Pahud.

About the Authors

Lyesse Laloui is Chair Professor, Head of the Soil Mechanics, Geoengineering and CO2 storage Laboratory and Director of Civil Engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Alice Di Donna is a researcher at the Laboratory of Soil Mechanics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART 1

Physical Modeling of Energy Piles at Different Scales

Chapter 1

Soil Response under Thermomechanical Conditions Imposed by Energy Geostructures

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Thermomechanical behavior of soils

| Material | Volumetric thermal expansion coefficient [10–6°C–1] |

| Muscovite | 24.8 |

| Kaolinite | 29.0 |

| Chlorite | 31.2 |

| Illite | 25.0 |

| Smectite | 39.0 |

| Water | 139 + 6.1-T |

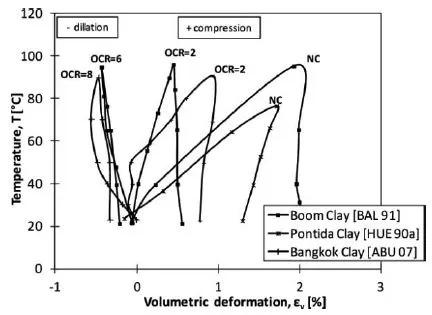

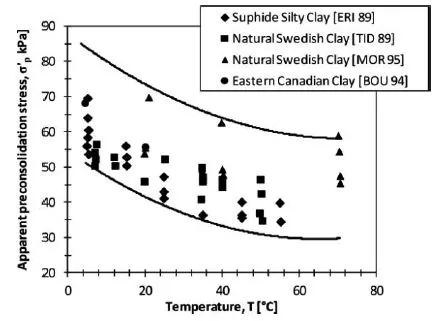

1.2.1. Thermomechanical behavior of clays

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- PART 1: Physical Modeling of Energy Piles at Different Scales

- PART 2: Numerical Modeling of Energy Geostructures

- PART 3: Engineering Practice

- List of Authors

- Index