- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Philosophy and the Study of Religions: A Manifesto advocates a radical transformation of the discipline from its current, narrow focus on questions of God, to a fully global form of critical reflection on religions in all their variety and dimensions.

- Opens the discipline of philosophy of religion to the religious diversity that characterizes the world today

- Builds bridges between philosophy of religion and the other interpretative and explanatory approaches in the field of religious studies

- Provides a manifesto for a global approach to the subject that is a practice-centred rather than a belief-centred activity

- Gives attention to reflexive critical studies of 'religion' as socially constructed and historically located

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philosophy and the Study of Religions by Kevin Schilbrack in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Full Task of Philosophy of Religion

i. What is “Traditional Philosophy of Religion”?

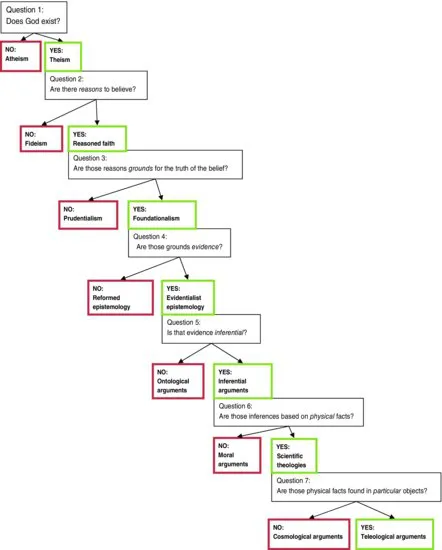

In this book, I am arguing that philosophy of religion should expand the traditional understanding of its task and take a broader view. Here at the beginning, however, I want to put on the table what my alternative is an alternative to. “Traditional philosophy of religion” defines its task in terms of the rationality of theism and this is the primary focus found in most philosophy of religion journals, textbooks, and courses.1 As I mentioned in the preface, my critique of traditional philosophy of religion is that it is it narrow, intellectualist, and insular. Despite that critique, I am not arguing that traditional philosophy of religion is not a rich and multifaceted discipline. Here is one way that one can organize the variety of the central debates in the traditional approach. (I use a flowchart to map these debates, and it may help to follow that chart in Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1 Traditional Philosophy of Religion: A Flow Chart.

First, the most basic division in the field comes between those theists who argue that there exists a being worthy of worship and those who argue that there does not (or that, if there does, we cannot know it). Some of the atheist or naturalist philosophers in this latter camp hold that belief in a God of perfect power and benevolence cannot be reconciled with experiences of gratuitous evil. They argue either that, given those painful and demoralizing experiences, the claim that a benevolent God is decisively disproven or at least that, given the amount of suffering in the world, the truth of the claim is unlikely. Other naturalists argue that we cannot make sense of the unusual idea of a being who knows the future or that is all-powerful or that exists necessarily. Others in this camp argue that the lack of a clear revelation or experience of God—what is sometimes called “divine hiddenness”—justifies skepticism about God's existence. Such views have been popularized in bestselling books by the so-called New Atheists, and some atheist or naturalist philosophers of religion have developed their positions with great sophistication.

By contrast, the philosophers of religion who are theists hold that there does exist a being worthy of worship. I divide the theistic philosophers into two camps. The first maintains that the faith that God exists is the kind of commitment that can be supported by reasons, reasons intelligible to those who do not yet share that commitment. Let's call this commitment: reasoned faith. I will come back to this group. The other group of theists holds that faith in God, properly understood, is not the kind of commitment that can be supported by such reasons. These theists are persuaded, for example, by Søren Kierkegaard's account of faith as a passionate and subjective commitment, or by Richard Braithwaite's account of faith as an attitude about one's values and not about facts, or by Ludwig Wittgenstein's account of faith as drawing its sense from a set of ungrounded practices or form of life. Philosophers of religion in this camp hold that there are no criteria by which faith can be justified that are not internal to that commitment or way of looking at the world. Call these theists: fideists. As an illustration of fideism, consider the philosophers of religion who are inspired by Wittgenstein's observations about religion when he says, “The point [of belief in God] is that if there were evidence, this would in fact destroy the whole business. Anything that I would normally call evidence wouldn't in the slightest influence me.”2 From this perspective, what religious communities teach is not a set of opinions or hypotheses or truth claims that can be compared to facts about the world, but rather ways of living and speaking. To agree with the fideists that theistic beliefs are not held on the basis of reasons is not necessarily to consider religion unreasonable. As Wittgenstein says, those who believe in God “don't treat this as a matter of reasonability.” Fideists therefore argue that one misinterprets theistic beliefs if one thinks that they are either warranted or unwarranted, and the task of philosophy of religion for those in this camp is not to assess the warrant or justification for belief in God. The task, instead, is to clarify what it means to live and speak as a believer.

Let me now return to those theists who do seek to marshal a reasoned faith. I also subdivide these philosophers of religion into two camps: on the one hand, there are those who argue that it is reasonable to believe in God because, they argue, one can provide some grounds that belief in God is true. Call these theists: foundationalists. I will come back to this group of philosophers in a moment. The other group of theists argues that although the belief that God exists, properly understood, is not the kind of belief that one can prove true, or even probable, theism can nevertheless be reasonable. They make a prudential case that it is good to believe or that one ought to believe that God exists. Theism might be reasonable simply because, as Blaise Pascal famously argues, given the eternal stakes at play, it is in one's interest to believe. (As a billboard near my house similarly suggests: “If you are living as if God does not exist, you had better be right,” and the bottom of the billboard is covered with flames.) William James also proposes a way of believing reasonably without grounds. In a trenchant analogy, he says: if a mountain climber becomes stuck on a precipice and, to get back home, she needs to make a jump that she has never made before and cannot prove that she can make, it is still reasonable for her to believe that she can (and must!) make the jump, and it is still reasonable for her to attempt the jump, rather than staying stuck on the mountain.3 Such arguments don't offer grounds that theism is true, though they do offer reasons to believe it.

The foundationalists who argue that there are grounds for the belief that God exists I divide based on whether they hold that the grounds are direct or indirect. One example of direct grounds for belief is perception. To take an example, in a case when I am having a face to face talk with my brother, I would believe the proposition this is my brother, and I would be warranted in doing so, but we would not say that I believe because I have evidence or clues from which I was able to infer that this is my brother. If someone asked me afterwards, “How did you know that it was your brother you were talking to?,” I could answer, “Because he was right there.” My reason for belief is not indirect or via any other belief. Analogously, these theistic philosophers argue that those who believe in God do not do so because they have evidence or clues from which they are able to infer that God exists. Rather, they believe that God exists, and they do so justifiably, because they simply perceive God's presence. They point out that, in fact, we hold many beliefs in this direct way: the belief that the world is more than five minutes old and the belief that other people are not robots are not beliefs that we base on careful examination of the evidence. These philosophers argue that the theistic belief in God, like the memory belief that I had a grapefruit for breakfast or the perceptual belief that there is a cup in front of me right now, is grounded directly. It is a belief on which other beliefs can then come to be based. In this way, theism can structure the practices and values that make up one's life, but it is based in a foundational way on direct experience and not on other beliefs that are more basic.

Other theistic philosophers hold that apart from these claims of perceiving God directly, there is indirect evidence that God exists. Call this latter group: evidentialists. When we speak of “evidence,” we typically mean something that points to a reality that is not present. For example, a fingerprint can be evidence left by the perpetrator or smoke from a window can be evidence that there is a fire inside. One infers from the evidence a cause that could have brought it about, and so evidence like this can be called inferential evidence. But some evidentialists argue that God is such a distinctive reality that God's existence can be demonstrated with evidence that is not inferential. They argue that if God is properly understood as a reality that is worthy of worship, a reality that is perfect, then God's mode of existence by definition cannot be limited or weak or contingent or dependent. If it is God about whom we are speaking, then we cannot be speaking about a reality that was brought into existence or a reality that might conceivably cease to exist. God therefore must exist not only in some places or some times, but always and everywhere, neither brought into existence by something else nor capable of not existing. If God by definition has every good quality, then God by definition has the quality of necessary, non-contingent existence. And if God's existence is necessary, contingent on nothing, then God exists under all conditions. And so God must exist. Though this argument is often dismissed on the grounds that one cannot simply define a reality so carefully that—poof—that reality must exist, there is no confusion in saying that a being worthy of worship would be one that exists under all conditions.

The theistic philosophers who argue for the existence of God based on inferential evidence claim that, just as smoke serves as a sign that there is a fire, there are realities in the world of human experience that point to the existence of a divine being. Some philosophers in this camp point at physical evidence that is external to the subject. More on them in a moment. Others, however, argue that the clues for God's existence are internal and non-physical. Some argue that the best evidence from which one can infer a divine reality is morality. C. S. Lewis is a philosopher who argues in this way, holding that when people look inside themselves, they find a moral law that is not a product of human imagination or social practices, “a real law which we did not invent and know that we ought to obey.”4 If the universe is the source of that law—the mailman who put that letter in our mental mailbox, to use Lewis's metaphor—then it must be or include something like a mind, at least in the sense that it gives instructions and cares about how human beings act. Immanuel Kant also uses the experience of a moral law as evidence for theism. Kant does not infer that God must be the source of the law that one finds in one's conscience. He argues, instead, that if the moral law is not incoherent, then the happiness one earns in one's life must be proportioned to the virtue one develops. It seems painfully clear that such proportioning does not happen in this life, however, and therefore one must take as a practical hypothesis or “postulate” that God as a moral judge of the world and immortality are real.

Now consider those philosophers of religion who are theists, who hold that one can give reasons for one's faith, that these reasons serve as grounds that their beliefs are true, that the grounds are evidence, that the evidence is inferential, and that the inferences are based on facts about the physical world. These philosophers of religion argue that there are facts about the natural world from which one can infer a supernatural creator. Such arguments can be usefully distinguished into two general kinds: some of these arguments are based on particular objects or facts about the natural world, and others are based on facts about the general character of natural things. The classic example of the first strategy is William Paley's early nineteenth century argument that there are objects in the natural world whose purposeful functions can only be explained by an intelligent designer. The anatomy of the eye, for instance—including the cornea, the iris, the lens, the pupil, the chambers with their aqueous and vitreous humors, the retina, and so on, all working together to give sight to the creature—requires an explanation that the natural world alone cannot supply. Michael Behe has recently updated and strengthened this kind of argument for a supernatural designer. As complex as the anatomy of the eye is, Behe points out, it is nothing to the staggering complexity of the biochemistry of vision, the mechanisms of protein chains that respond to light by creating electrical nerve impulses. Such operations at the molecular level within the cells used to be a mystery, a “black box” to science. But now that the black box has been opened by biochemists, one can see that the mechanisms are irreducibly complex—in the crucial sense that if one part of the system were removed, the system would not function. Because they are irreducibly complex, the emergence of some parts of the natural world is inexplicable through blind chance and the gradual stages of natural selection; they therefore point to the existence of an intelligent designer.5

Those philosophers of religion who take up the second strategy base their arguments for God's existence not on the character of some particularly remarkable objects or states of affairs in the world, such as the eye or the apparently perfect adjustment of natural laws for intelligent life—but rather on facts about physical things in general. These are cosmological theistic arguments. One cosmological argument states that if every single physical thing is contingent, in the sense that it might not have existed, then it seems that the same contingency equally applies to the set of all physical things. If we call this set of all physical things “the universe,” then we can say that the universe as a whole is contingent and might not have existed. One might therefore legitimately wonder why anything exists at all. Why is there something rather than nothing? The only answer for that question would be some reality whose existence is not contingent—that is, a being that is different from the universe and everything in it because its existence is necessary. In another cosmological argument, theistic philosophers of religion argue that if every physical thing requires a cause, and the chain of causes stretches back through history of the cosmos, then at the beginning of time then there must be a first cause. They argue that the existence of God answers the question about the origin of the universe as a whole. For example, some theists hold that the scientific evidence that the world began roughly fifteen billion years ago in a Big Bang gives people reason to believe that the natural world must have a creator. The idea that the world has not always existed but rather began to exist a finite amount of time ago is a recent development in physics and, as William Lane Craig has pointed out, this remarkable, new scientific evidence lends support to those theists who believe that the world was created. Drawing on what is sometimes called the Kalam argument, after the Islamic philosophical theologians who first employed it, Craig argues that if everything that begins to exist is caused, and the universe began to exist (as the Big Bang theory holds), then these two truths together point to the need for a cause for the physical universe, a supernatural first cause of everything.

As one can see, the questions pursued in traditional philosophy of religion cover a very wide set of questions. Traditional philosophy of religion draws on debates in physics, biology, ethical theory, and modal logic. It also contributes to Christian theology and to Biblical studies. This fruitfulness notwithstanding, one can see that traditional philosophy of religion has focused on a relatively narrow topic: the rationality of belief in God. Even the philosophers of religion who are skeptics or atheists fit that description of the discipline.

There are some forms of philosophy of religion that do not focus on the kind of theistic and atheistic arguments that I have listed. For example, when we turn to philosophy of religion as it is practiced in non-Anglophone, Continental Europe, we find an approach quite different from the topics just listed. In Continental philosophy of religion, one does not find a focus on the characteristics that God must have or proofs for the existence of God. Instead, one finds a focus on religious experience, on the phenomenology of overflow experiences, and on overcoming ontotheology. Continental philosophy of religion primarily reflects on the limits of reason and on faith as a response to revelation. It is primarily concerned with the nature and limits of God-talk rather than with warrant for truth claims. Nevertheless, as one sees in John Caputo's definition of religion simply as “the love of God,” Continental philosophers of religion predominantly share with analytic philosophers of religion the narrow focus on theism. In fact, as Christina Gschwandtner points out, almost all the Continental philosophers of religion from France—including Paul Ricoeur, Jean-Luc Marion, Michel Henry, Jean-Louis Chrétien, Jean-Yves Lacoste, and Emmanuel Falque—are apologists for the coherence of thought about God and for the viability of religious experience.6 Another approach that does not pursue the theistic and atheistic arguments I listed is found in feminist philosophy of religion. Whether feminist philosophers of religion use the analytic approach or (more commonly) the Continental approach, they typically focus on the biases and distortions woven into traditional, masculine accounts of God and how these might be avoided. But the questions of theism are still usually central. Continental philosophy of religion and feminist philosophy of religion thus share a view of their task that is limited in the ways described in this chapter and to that extent they too should develop along the three axes I recommend in the rest of this chapter.

I begin this book with this enumeration of the variety of topics one finds in traditional philosophy of religion because I do not want to give the sense that traditional philosophy of religion is not already a complex and evolving discipline. As I mentioned, in one sense, the discipline is f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: The Full Task of Philosophy of Religion

- Chapter 2: Are Religious Practices Philosophical?

- Chapter 3: Must Religious People Have Religious Beliefs?

- Chapter 4: Do Religions Exist?

- Chapter 5: What Isn't Religion?

- Chapter 6: Are Religions Out of Touch With Reality?

- Chapter 7: The Academic Study of Religions: a Map With Bridges

- Works Cited

- Index