![]()

Chapter 1

Polymer Nanotube Nanocomposites: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Properties and Applications

Joel Fawaz and Vikas Mittal*

Department of Chemical Engineering, The Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Abstract

Owing to their high mechanical and electrical properties, nanotubes are ideal fillers for the generation of composites. Polymer nanotube nanocomposites are synthesized after achieving suitable surface modifications of the nanotubes using different synthesis methods like melt mixing, in-situ polymerization and solution mixing. All these methods have their own advantages and limitations and varying degrees of success in achieving nanoscale dispersion of nanotubes in addition to achieving significant property enhancement in the composite properties. The tensile modulus is generally reported to be significantly enhanced on the incorporation of even small amounts of nanotubes. Though the tensile strength and elongation at break in many cases are reported to improve, they are more likely dependent on the morphology of the nanocomposites. The glass transition temperature as well as degradation temperature are also observed to significantly increase mostly owing to the reinforcing effect of nanotubes. Many other properties like electrical conductivity, heat deflection temperature, etc., also increase on the addition of nanotubes to the polymer.

Keywords: Nanocomposites, dispersion, aspect ratio, in situ, melt, morphology, tensile properties, glass transition temperature, degradation, functionalization, electrical conductivity, resistivity

1.1 Introduction

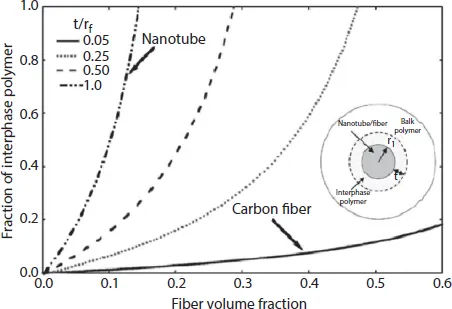

Many experimental and theoretical studies have reported the modulus of the nanotubes to be in the same range as graphite fibers and even the strength at least an order of magnitude higher than the graphite fibers [1–11]. In any case, even if the real mechanical properties of nanotubes are actually somewhat lower than the estimated values, nanotubes still represent high potential filler materials for the synthesis of polymer nanocomposites. The surface area per unit volume of nanotubes is also much larger than the other filler fibers, leading to much larger nanotube/matrix interfacial area in the nanotube-reinforced composites than in traditional fiber-reinforced composites. Figure 1.1 represents such an interface polymer fraction in nanotube-reinforced polymers where the ratio of the thickness t of the interphase versus the inclusion radius rf is plotted with respect to the volume fraction of the inclusion [1]. Owing to the interfacial contacts with the nanotubes, the interfacial polymer has much different properties than the bulk polymer. The conversion of a large amount of polymer into interface polymer fraction due to the nanoscale dispersion and high surface area of nanotubes generates altogether different morphology in the nanotube nanocomposites, which results in the synergistic improvement in the nanocomposite properties. In order to achieve optimized interfacial interactions between the polymer and nanotubes, nanoscale dispersion of the filler is required, which necessitates compatibilization of the polymer and inorganic phases. Therefore, the nanotubes need to be surface modified before their incorporation into the polymer matrix. Therefore, as CNTs agglomerate, bundle together and entangle, it may lead to defect sites in the composites, subsequently limiting the impact of CNTs on nanocomposite properties. Salvetat et al. [12] studied the effect of CNTs dispersion on the mechanical properties of nanotube-reinforced nanocomposites, and it was observed that poor dispersion and rope-like entanglement of CNTs caused significant weakening of the composites. Thus, alignment of CNTs is also equally important to enhance the properties of polymer/CNT composites [13,14]. Stress transfer property of the nanotubes in the composites is another parameter which controls the mechanical performance of the composite materials. Many studies using tensile tests on nanotube/polymer nanocomposites have reported the bonding behavior between the nanotubes and the matrix [15,16], in which there was an interfacial shear strength ranging from 35 to 376 MPa. The range of values was due to the different diameters of the nanotubes and the number of wall layers. However, other behaviors have also been reported based on interfacial compatibility. In their study, Lau and Hui [17] observed that most of the nanotubes were pulled out during the tensile testing owing to no interaction at the interface.

It has also been reported that in the case of multiwalled nanotubes, the inner layers of nanotubes cannot effectively take any tensile loads applied at both ends owing to the weak stress transferability between the layers of the nanotubes [8,18]. This results in the outmost layer of the nanotubes taking the entire load. As a result, the failure of the multiwalled nanotubes could start at the outermost layer by breaking the bonds among carbon atoms.

Nanotube nanocomposites with a large number of polymer matrices have been reported in recent years. The composites were synthesized in order to enhance mechanical, thermal and electrical properties of the conventional polymers so as to expand their spectrum of applications. Different synthesis routes have also been developed in order to achieve nanocomposites. The generated morphology in the composites and the resulting composite properties were reported to be affected by the nature of the polymer, nature of the nanotube modification, synthesis process, amount of the inorganic filler, etc. This chapter reviews nanocomposite structures and properties reported in a few of these reports and also stresses the future potential of nanotube nanocomposites by mentioning some of their reported applications. Recent reviews were published and can be found in [19–21].

1.2 Methods of Nanotube Nanocomposites Synthesis

1.2.1 Direct Mixing

This method, unlike the others, is used only for thermoset polymers. The carbon nanotubes are dispersed into a low viscosity thermosetting resin, usually epoxy, by mechanical mixing or sonication [22]. Afterwards, the mixture is cured to produce the nanocomposite. Another direct mixing technique involves the use of solvent to lower the viscosity of the epoxy resin [23]. The CNTs are first exfoliated in ethanol under sonication before mixing them with the epoxy resin. Once dispersion is obtained, the solvent is evaporated and hardener is added to trap the CNTs in the polymer matrix.

1.2.2 Solution Mixing

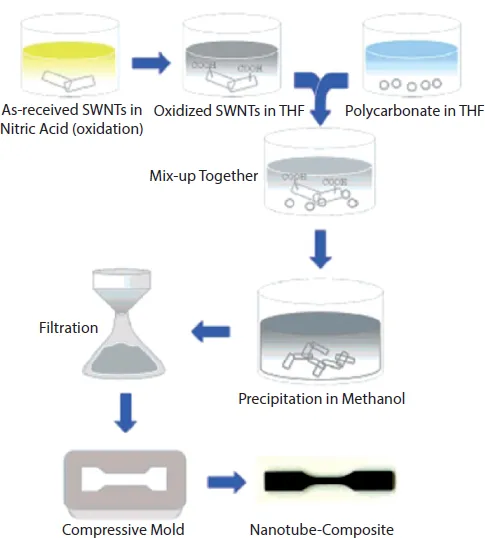

Solution mixing method has the advantage that the viscosity of the system can be controlled to be low so as to achieve higher extents of nanotube dispersion in the polymer systems. Both thermoset and thermoplastic polymers can be employed using this approach to achieve nanocomposites. The disadvantage associated with this method is, however, the requirement of a large amount of solvent for the nanocomposite synthesis, which for industrial applications may not be environmentally friendly or cost effective. For thermoset nanocomposites, one can also use the prepolymer to disperse the nanotubes and the prepolymer can then be crosslinked during the evaporation of solvent. Suhr et al. [19] reported the solution mixing approach as shown in Figure 1.2 for the synthesis of polycarbonate nanocomposites. The nanotubes were first oxidized in nitric acid before dispersion as the acidic groups on the sidewalls of the nanotubes can interact with the carbonate groups in the polycarbonate chains. To achieve nanocomposites, the oxidized nanotubes were dispersed in THF and were added to a separate solution of polycarbonate in THF. The suspension was then precipitated in methanol and the precipitated nanocomposite material was recovered by filtration. From the scanning electron microscopy investigation of the fracture surface of nanotubes, the authors observed a uniform distribution of the nanotubes in the polycarbonate matrix [24].

Similarly, Biercuk et al. [25] reported the use of a solution mixing approach for the synthesis of epoxy nanocomposites. Epoxy prepolymer was dissolved in solvent in which the CNTs were also uniformly dispersed. The solvent was subsequently evaporated, and the epoxy prepolymer was crosslinked. The resulting nanocomposite was reported to have a good dispersion of nanotubes. In other studies, multiwalled nanotubes were mixed in toluene in which polystyrene polymer was dissolved [26, 27] to generate polystyrene nanocomposites. The nanocomposites were generated both by film-casting and spin-casting processes. The solution mixing method has also been used to attain alignment of the nanotubes in the composites [28,29]. Aspect ratio and rigidity of the nanotubes were reported to be the two factors which affect the alignment of the nanotubes. If the nanotubes were longer and more flexible, the alignment of the nanotubes in the composites was observed to deteriorate [30,31]. Stretching the cast film of the nanocomposite synthesized by the solution-mixing method resulted in the improvement of the nanotube alignment [30].

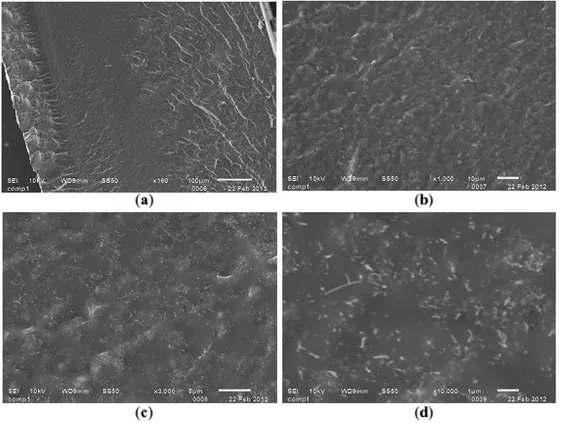

Liu and Choi [32] reported high quality dispersion of MWNTs at concentrations up to 9 wt% in poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) matrix using solution mixing. For better dispersion, a systemic study was conducted to determine the optimal solvent for both CNTs and PDMS. Chloroform was selected over the other common solvents, such as THF and DMF, due to its high solubility of the components and stability of the mixture. Moreover, functionalization of the CNTs by carboxyl groups further enhanced dispersion. The nanocomposite synthesis entailed the initial dispersion of fMWNTs in chloroform which was then sonicated for 1 hour. Meanwhile, PDMS base resin was dissolved in chloroform and magnetically stirred for 15 minutes. The separate mixtures were mixed together and sonicated for 1–2 hours. Solvent evaporation was efficiently performed by applying vacuum at elevated controlled temperatures. This process enabled the retainment of the initial dispersion as can be seen in the SEM images in Figure 1.3.

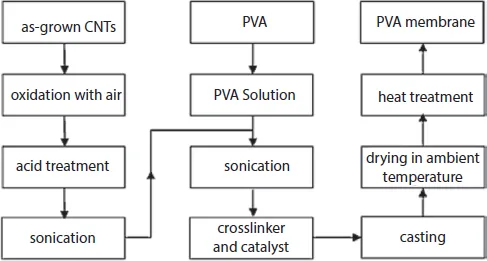

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/MWCNT nanocomposite membranes were reported by Shirazi et al. [33] as a means of dehydrating isopropanol. The nanocomposites were prepared by solution mixing in which PVA was dissolved and stirred in deionized water at 90°C followed by filtration and removal of bubbles by vacuum. CNTs are then added to the solution and ultrasonicated for 4 hours followed by the use of crosslinker and a catalyst. Figure 1.4 illustrates the procedure followed to prepare the membrane. Good dispersion of MWCNTs was achieved up to 2 wt% loading; whereas, increasing the loading above 2 wt% tended to cause agglomeration. Moreover, when measuring the outer diameter of the nanotubes in the 2 wt% loading nanocomposite, it was found to be similar to that of the neat CNT. On the other hand, in the 4 wt% loading nanocomposites, the diameter was measured to be higher, signaling the formation of CNT bundles.

Martone et al. [34] compared solution and direct mixing in terms of dispersion. Different solvents (ethanol, acetone and sodium dodecyl sulfate aqueous surfactant) and dispersion techniques (magnetic, mechanical and sonication) were used to disperse the CNTs in an epoxy matrix...