![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Importance of wildlife forensic science investigations

The scale of wildlife crime is difficult to judge accurately as so much may go undiscovered, unreported or unrecorded. The poaching of protected species by its very nature can occur in remote and isolated areas where there is little surveillance. As such, wildlife crime is more likely to be identified when samples are transported through border controls or other checkpoints.

Poaching of any kind can result in high financial rewards, a low chance of prosecution and penalties associated with convictions for wildlife crime are generally low. For these reasons there is an often quoted figure of something like:

‘The illegal trade in wildlife is a US$20 billion a year industry, second only to trade in illegal drugs’ (Zhang et al., 2008; Alacs et al., 2010).

The monetary figure will range between US$6 and 40 billion a year and is often attributed to Interpol, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) or another non-governmental organisation (NGO); however, Interpol have confirmed that they have never issued any statement to this effect (Christy, 2010). This figure, although believable (considering the cost of individual animal components), is difficult to estimate as monitoring the amount of illegal trade is itself the problem. It is at best an estimate as there are not the same international surveillance methods used in other areas of international criminal activity, such as drug enforcement or the trade in firearms, to investigate and prosecute offences involving wildlife. Organised crime has not been proven to be linked to wildlife crime, but there are indications that this could be the case (Sellar, 2009). Another influencing factor in wildlife crime is that there is a high financial return with little chance of capture, and even if captured, the penalties are light. Rarely does the maximum penalty for the alleged event meet the potential financial gains (Li et al., 2000).

These financial gains can be highlighted by a number of examples of the illegal trade in wildlife or products derived from protected species. These examples include the illegal trade in the ultra-fine fabric to make a shawl called a shahtoosh, which requires between three to five killed Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) to make one shawl and a single shawl can retail at between US$8000 and $10 000. Single Australian parrot eggs could fetch as much as US$30 000 on the international market (Alacs and Georges, 2008). The cost of ivory on the black market remains high with ivory being marketed as from mammoth. Mammoth, since extinct, are exempt from international regulations and so can be imported, exported and sold legally. The cost of mammoth ivory is currently on average US$350 per kilogram (different ‘grades’ of ivory sell for different amounts and the highest grade can retail for over US$500 per kg), equivalent to US$350 000 per tonne, and worth US$21 million per year to the Russian economy (Martin and Martin, 2010). A clear issue is to be able to distinguish between mammoth and elephant ivory to ensure that ivory sold as mammoth is not actually from an elephant, but more importantly the need to ensure that the growing trade in what is described as ‘mammoth’ ivory does not lead to the increased poaching of elephants in Africa.

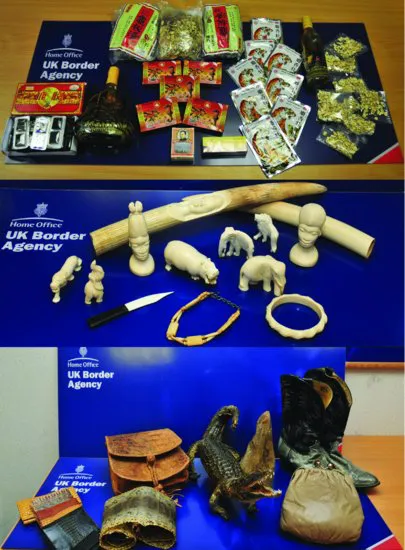

Traditional East Asian medicines (TEAM) still command a high price and an increasing market as populations in that part of the world increase. Other reasons include: human food consumption, such as bushmeat and shark fins; a symbol of wealth, such as dagger handles, ornaments and skins; as tourist curios which includes coral reef or wood carvings; and the live pet trade that includes snakes, geckos, parrots, and even primate species. As the deterrent is low with low levels of detection and minimal fines or prison sentences if caught, there is reason to believe that organised crime groupings are involved with illegal trade in wildlife due to the large financial rewards. For many species poached illegally, as they become more rare in the wild so they attract a higher value on the black market, and hence the trade is more lucrative to those unconcerned with their conservation (Courchamp et al., 2006). This is coupled with the problem that many highly prized (by some) species naturally occur in countries where the average wage is low and hence the financial attraction in poaching a wild animal is great. A distinction should be drawn between low level hunting by a local community who consider such activities as an ancestral right and harvesting on a commercial scale that has a detrimental effect on species numbers or activity driven by financial gain only.

The effect of trade in wildlife on particular species has been great, although in some cases the rapid decline in numbers is also associated with habitat loss. According to the recent census by the WWF only 3200 tigers (Panthera tigris spp.) exist in the wild. This is a reduction of over 90% from the last century, leading to more tigers existing in captivity in Texas alone than in the wild. The population of black rhino (Diceros bicornis) decreased by 96% between 1970 and 1992 (International Rhino Foundation); in 1970, it was estimated that there were approximately 65 000 black rhinos in Africa – but by 1993 there were only 2300 surviving in the wild. Intensive anti-poaching efforts have had encouraging results since 1996. Numbers had been recovering in some areas but not in countries where there is limited or no protection from poaching. The increase in the desire and cost for rhino horn has recently resulted in a significant increase in the killing of rhino. In South Africa the number of rhino shot for their horn was 13 in 2007, but this rose to 83 the next year, 122 in 2009, 333 in 2010, 448 in 2011 and is over 250 for the first half of 2012 (information from Dr Cindy Harper of the University of Pretoria). The estimated black market cost for genuine rhino horn is between US $20 000 and $90 000 per kilogram. Survival of those rhino that remain is due in no small part to the dedication of wildlife officers in the field (see The Thin Green Line web site www.thingreenline.info). In the case of the Western Black Rhino it was officially declared extinct on 10 November 2011 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The organisation stated further that two other subspecies of rhinos were close to meeting extinction. Central Africa's Northern White Rhino is possibly extinct in the wild and the Javan rhino is now thought to be extinct in Vietnam, after poachers killed the last surviving one there in 2011 for its horn. Tiger and rhino highlight the problem as they are high-profile species, but the situation is reflected with similar declines in many avian, reptilian and amphibian species. Some examples of products derived from wildlife contrary to CITES regulations are displayed in Figure 1.1.

1.2 Role of forensic science in wildlife crimes

Given the estimated size of the trade in wildlife, and the threat to species, it would be assumed that there is investment in forensic science to aid in combating these illegal activities. The types of forensic science methods pertinent to the enforcement of wildlife legislation include: veterinary pathology, where persons skilled in this discipline perform a similar role as their human counterparts and determine cause and time of death; crime scene examination, to record and collect evidence such as latent fingerprints and DNA, both of the animal and potential human DNA from the perpetrator (Tobe et al., 2011); morphology/microscopy, as simple comparison of hairs, furs and feather is often the first step in determining what species is present; ballistics, in the comparison of bullets recovered from carcasses to cartridge cases found at a poaching scene and a particular firearm if seized subsequently; document examination, to determine authenticity of documents relating to the trade in species; chemical profiling, to determine possible geographical origin based on isotope ratios; and DNA analysis to determine species and potentially link to a particular individual in a similar manner as their human counterpart. It is this last part that will be the focus of this book although it is important to realise that forensic science has many techniques that can be complementary. Forensic science has a range of tools and it is essential that the appropriate tool is used to address the allegation.

1.3 Legislation covering wildlife crime

Forensic science can only be employed if there is reason to believe that a piece of legislation has been breached and that there is a need for an investigation to determine whether a crime has occurred, and if so who committed the crime. Legislation relevant to wildlife crime falls under two broad areas: international and national.

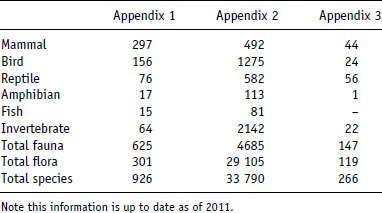

The international organisation that oversees the trade in protected species is the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna (CITES). Founded in 1973 it currently has 175 countries (known as Parties) as signatures to the Convention. The role of CITES is to monitor trade in species and recommend a ban of all trade in particular species when necessary. There are three appendices that underpin the role of CITES. Appendix I lists species that are threatened with extinction if trade is not prohibited. Trade is permitted only in exceptional circumstances such as the movement of samples/organisms for research or conservation purposes. Species on Appendix II are those that are not necessarily in danger of extinction but could become so if trade were not strictly regulated. Appendix II also contains some species that are not in themselves threatened but have similar morphology to a species that is endangered and hence allows better enforcement of trade for the endangered species. Those species on Appendix III are species which individual Parties to the Convention choose to make subject to regulations and for which the cooperation of other Parties is requested in controlling trade. Comprehensive information on the role of CITES with links to Appendices I, II and III can be found at www.cites.org. The numbers of some of the species listed currently under the three appendices are provided in Table 1.1. An example of the legislation and role of CITES in the trade of timber, and particularly mahogany products, is shown in Box 1.1.

Table 1.1 Number of species in the three CITES appendices. Based on data from CITES Secretariat.

Nationally, countries are required to enact laws in order to implement and enforce CITES, and additionally many countries have enacted laws to protect other wildlife within their borders. In Australia, the international movement of wildlife and wildlife products is regulated under Part 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversit...