- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Contemporary Latin America presents the epochal political, economic, social, and cultural changes in Latin America over the last 40 years and comprehensively examines their impact on life in the region, and beyond.

- Provides a fresh approach and a new interpretation of the seismic changes of the last 40 years in Latin America

- Introduces major themes from a humanistic and universal perspective, putting each subject in a context that readers can understand and relate to

- Focuses on 'Ibero-America'--Brazil and the eighteen countries that were formerly Spanish possessions- while offering valuable comparative views of the non-Iberian areas of the Caribbean

- Emphasizes the global, regional and national dimensions of the region's recent past

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Latin America by Robert H. Holden,Rina Villars in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Latin America in a World Setting

Introduction

Revolts against Spanish and Portuguese rule in the Americas after 1808 produced the nineteen countries that compose Latin America today. Yet no era in the post-independence histories of these countries can match the depth and scope of change that swept over their peoples in the decades after about 1970. The purpose of this book is to identify and weigh the distinctive local, national, regional and global dimensions of those changes.

Because of the compact nature of the period covered in this book, we opted to organize Latin America’s history since about 1970 around four big themes, each the subject of a separate “Part”: Government (II), Wealth (III), Culture (IV) and Communities (V). None outranks the others in importance, nor can any stand alone as the ultimate “cause” of change. We have chosen them because a survey of Latin America’s history since 1970 should supply the broadest view of the essential aspects of the topic. We believe that these themes (plus that of beliefs, the subject of Chapter 2) encompass what is most vital to know about the history of any given human society. None can be plausibly analyzed without reference to their global dimensions, which every chapter takes into account.

Thus, change after about 1970 will be the core historical problem of each of the chapters that follow. While in most cases the evidence for epochal change revealed itself only in the 1980s, our account begins with the previous decade because the multiple crises of the 1970s opened the door for the reforms that would mark the 1980s.

Understanding change requires clarity about the subject of change. The introductions to each of the parts that follow this one will therefore define the theme and explain its significance in the larger context of Latin American history.

In the first chapter, we elaborate our general interpretation of the trends of the last four decades: toward liberalization, by which we mean a loosening of restraints, a tendency toward inclusiveness, an openness to experimentation. On balance, of course, there is much more evidence of continuity than of change, as one would expect in a period of such short duration. And not every kind of change has come down on the side of liberalization.

Moreover, the movement toward liberalization in the areas that constitute the topics of Parts II to V can be expected, if carried far enough, to generate resistance and countertrends. Evidence for both is not hard to find, as we will see.

In Chapter 1, we set out to define the region, survey its more distant past, and situate it globally. We go on in Chapter 2 to characterize the array of beliefs and values that ultimately account for the distinctiveness of our nineteen countries, and thus for their status as a separate world region or civilization.

Chapter 1

What Is Latin America?

“Latin America” as the preeminent name of the lands to the south of the United States first emerged in the mid-1850s. Until then, they were normally referred to as “Spanish America” or “South America” by both English and Spanish speakers. While the origins of the term remain controversial among historians, it seems likely that two trends intersected that together gave rise to a preference for “Latin America.” The first was the belief that the people of the world could be divided into separate races, each with their own distinctive temperaments and capacities. Race as the dominant explanation for the material progress of some peoples and the backwardness of others would gain currency everywhere in the nineteenth century. Second, as leading thinkers in the new republics worried increasingly about the political and cultural challenges posed by the United States, they sought to distinguish between what some considered a northern “race” of Anglo-Saxons or Yankees, on the one hand, and a contrasting “race” of Latins, on the other. At the same time, France popularized the name “Latin America” in the 1860s when it tried to justify its military invasion and occupation of Mexico by claiming a shared “Latin” racial and linguistic legacy with Mexico and the rest of the territories south of the United States. By the late nineteenth century, “Latin America” had become the preferred designation. In a nutshell, acceptance of the qualifier “Latin” seems to have represented an attempt to endow a strictly linguistic phenomenon (the strong dependence of Spanish, Portuguese and French on the Latin language) with a wholly imaginary Latin ethnicity. Even linguistically, of course, “Latin America” falls short in view of the continued vitality of hundreds of indigenous languages in most of the eighteen countries whose official language is Spanish, or in Portuguese-speaking Brazil.

“Latin America” seems even less appropriate when applied to all the lands south of the United States, a practice not uncommon among scholars of the region nor within some international organizations like the World Bank and the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America. This maximal interpretation of the region’s limits would encompass thirty-three independent, self-governing states and the fourteen dependencies of three European countries (France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) and of the United States. While numerous, all the dependencies are clustered in the Caribbean Basin (except for the UK’s Falkland Islands) and together they account for no more than 1% of the population and one-half of 1% of all the territory to the south of the United States. Of the thirty-three independent states that make up the maximal definition, half (sixteen) gained their sovereignty in the twentieth century and lie in the Caribbean Basin, but account for less than 4% of today’s population and only 3% of the territory to the south of the United States. All sixteen had been British territory since at least the eighteenth century except for Cuba (a Spanish colony until 1898, then a U.S. protectorate until 1934), Panama (a province of Colombia until 1903) and Suriname (a colony of the Netherlands until 1975).

In the eighteen other countries, political independence and decolonization were a nineteenth-century affair. They are: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. If we drop the formerly French possession of Haiti (overwhelmingly Afro-American in culture) and add Cuba and Panama to the list, we find these nineteen countries comprise 97% of the territory and 96% of the population south of the United States. They share some important characteristics that justify treating them as a cohesive entity:

- All of them except Brazil (formerly a possession of the Portuguese monarchy) were settled, colonized and governed for at least three centuries by the monarchy of Spain.

- A common process of independence (1810 to 1825) complemented the shared experience of three centuries of Spanish or Portuguese rule. The only exceptions are the island nations of Cuba and the Dominican Republic.

- During the nearly two centuries of self-rule that Brazil and most of Spain’s former territories have passed through since the 1820s, turbulence and violence, including frequent disruptions of constitutional order and authoritarian rule, have defined their political histories. Writing in the late 1970s, the social scientist and future Brazilian president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, could still compare the status of democracy in Latin America to that of an “exotic plant.” Not even today would most scholars consider any of the nineteen to be fully consolidated democracies, with the possible exceptions of Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay.

- Spanish is the official language in eighteen of the nineteen countries, while Portuguese is spoken in Brazil; both reign over a diversity of indigenous languages. Another important cultural trait was the near-monolithic adherence, until the late twentieth century, to the Roman Catholic religion in all nineteen countries.

- Finally, the economic geography of the nineteen countries reveals important regional consistencies. The World Bank, for example, classifies all the world’s economies as either developed (industrialized countries with high incomes and high standards of living) or developing economies (countries with low or mid-level incomes). All nineteen are “developing” economies, and their average level of development (as measured by life expectancy, education and purchasing power) is the highest of all the developing world regions. However, despite their average superiority in standard-of-living compared to other developing regions, our nineteen countries stand out in global terms as a region of extreme inequality of income. In the late 1990s, in most of the nineteen, the richest 10% of individuals were receiving 40% to 47% of total income while the poorest 20% were earning 2% to 4% of total income. Few countries in the world could match that record.

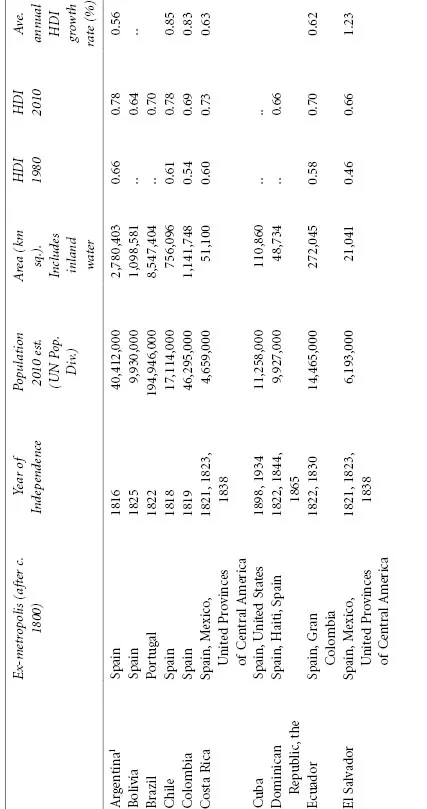

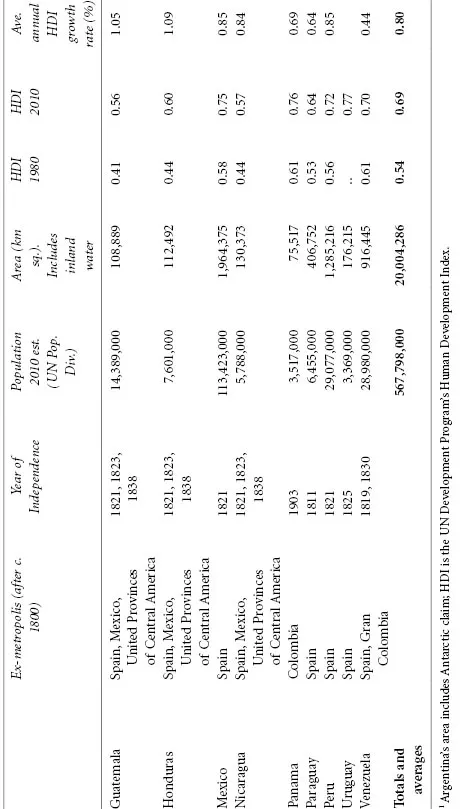

Taken together, these features indicate that in their common political history, geographical proximity, economies and basic cultural orientation, the eighteen Spanish-speaking countries and Portuguese-speaking Brazil (Table 1.1) make up a coherent and distinctive region, and thus constitute what we will refer to throughout this book as “Latin America.” We exclude Puerto Rico, despite its people’s success in preserving much of the culture that it inherited from its 400-year experience as a realm of the Spanish monarchy. Since its forced incorporation into the United States in 1898, followed in 1917 by the imposition of U.S. citizenship on its people, Puerto Rico has been largely isolated from the dominant patterns of social, economic and political change that will occupy us in this book.

Table 1.1 Latin America: basic demography, living standards and history.

Based on data from South America, Central America and the Caribbean 2006 (London: Routledge, 2006); United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2010; World Population Prospects, the 2010 Revision (UN Population Division, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Excel-Data/population.htm).

What we have just defined as Latin America is sometimes referred to as “Iberoamerica” or “Hispanic America.” “Iberia” was the ancient name for the peninsula now constituted by the modern nations of Spain and Portugal. “Hispanic” derives from the Latin Hispania, the name the Romans gave the Iberian peninsula when it was a province of their empire. Portugal and (by extension) Brazil can be associated with a more fanciful “Lusitanian” legacy, a name derived from Lusitanus, the Roman designation for the part of western Hispania out of which Portugal would one day emerge. The fact that the Romans called all of the Iberian peninsula “Hispania,” of which “Lusitania” was a part, might justify calling both Brazil and the Spanish-speaking republics together “Hispanic America.” While contemporary usage tends to associate “Hispanic” exclusively with Spain and the Spanish language, the peninsular scope of “Hispania” in Roman times reminds us of the extremely close affinity between the cultures and languages of Spain and Portugal, and thus between Brazil today and the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America. Along with most of the rest of Iberia, the Christian territories of the western third of the peninsula were conquered by the Islamic Umayyad Empire in 715 AD. The lands that would one day become known as Portugal thus participated in the reconquista or reconquest of Iberia by Christian armies, an enterprise that would continue until 1492. During the reconquest, the lands that would someday comprise the nation of Portugal came under the control of the kingdom of Castile y León, the preeminent power on the peninsula. When Portugal emerged as an independent kingdom in the twelfth century, it still lacked both a common language and a distinct tradition, for it had come into existence largely as a result of fortuitous politico-military developments arising from feudalism and the reconquest. Portuguese did not take its place as a national language distinct from Spanish (but strongly resembling it) until the early fourteenth century. Fear of reabsorption into the Spanish-speaking part of the peninsula persisted for centuries, but became a reality only once, when King Philip II of Castile seized Portugal in 1581. An armed revolt against Castile in 1640 resulted in the restoration of Portuguese independence, under the rule of the Braganza family.

Thus, although they have been politically separate for the better part of a millennium, Spain and Portugal (and their former American territories) nevertheless share a distinctive legacy of ideas, values and beliefs whose influence can be seen in literature, law, social custom, politics, religion, architecture and the arts. The Spanish monarchy in particular set out to make its New World kingdoms even more centralized, homogeneous, religiously orthodox and culturally unified than its own peninsular kingdoms. That policy was largely successful, and accounts for the remarkable sense of trans-national solidarity and shared values that has made Latin America the world’s largest multinational culture zone – both more unified and more diverse than Europe, as the Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes has pointed out.1 In places with high concentrations of indigenous and Afro-American peoples, customs and beliefs associated with those cultures continue to thrive, though invariably subordinated to an Iberian-oriented national culture.

Regardless of their identity as citizens of one country or another, or as members of particular ethnic groups or social classes, the peoples of the region habitually reflect on their experiences across national boundaries, and often seek to coordinate their responses to similar situations. In doing so, they act on the presumption that they share something larger, and more intangible, than the hard political facts of their common past.

An example in action was the university reform movement, launched by the students of a single Argentine university in 1918. Within a decade, it swept Latin America, transforming students into a potent interest group almost everywhere, while profoundly altering the political landscape. Similarly, the example of the Cuban revolution of 1959 ignited insurrectionary movements across the region, from Mexico to Argentina, in the 1960s and 1970s. Numerous other instances could be plucked from the realms of literature, music and other forms of popular entertainment. The Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez’s great novel Cien Años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) topped the bestseller lists in every country of the region soon after it was published in 1967. Two years later, the Peruvian songwriter, Daniel Camino Díez, wrote “Los Cien Años de Macondo,” celebrating the novel’s main characters. Numerous singers recorded it, but the Mexican singer Oscar Chávez’s version became a hit everywhere, as radio stations from rural Honduras to Santiago de Chile played the song repeatedly, inspiring many listeners to read the novel for the first time. This and countless other episodes like it cannot be explained by a common language alone, but above all by a common history and a common cultural orientation.

History

As recently as the beginning of the last quarter of the eighteenth century, most of the Americas had been part of the overseas territory of some European empire. Then, first Great Britain (between 1776 and 1783) and later Spain and Portugal (between 18...

Table of contents

- Cover

- A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Maps, Figures and Tables

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Latin America in a World Setting

- Part II: Government

- Part III: Wealth

- Part IV: Culture

- Part V: Communities

- Sources Consulted

- Index