Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals

About this book

Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals offers fast access to clinically relevant information on managing the patient with endocrine disease. Written by leading experts in veterinary endocrinology, each chapter takes the same structure to aid in the rapid retrieval of information, offering information on pathogenesis, signalment, clinical signs, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and prevention for a broad list of endocrine disorders. Chapters begin with brief summaries for quick reference, then delve into greater detail.

With complete coverage of the most common endocrine diseases, the book includes chapters on conditions in dogs, cats, horses, ferrets, reptiles, and other species. Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals is a highly practical resource for any veterinarian treating these common diseases.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Hypoadrenocorticism in Dogs

- Primary hypoadrenocorticism results from the destruction of >90% of the adrenal cortex.

- Most cases are presumed to be due to an immune-mediated process.

- Combined glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency occur most frequently, but isolated glucocorticoid deficiency (“atypical hypoadrenocorticism”) is probably underdiagnosed.

- Young to middle-age dogs are predisposed, as are poodles, West Highland White Terriers, and Great Danes.

- Addison’s disease is known as the “Great Pretender” because nonspecific signs such as lethargy, decreased appetite, and weight loss predominate.

- Gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting and diarrhea are also common.

- Patients may present in hypovolemic shock or following collapse.

- ACTH stimulation test demonstrates minimal cortisol response.

- Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid supplementation, ± intravenous fluids and supportive therapy.

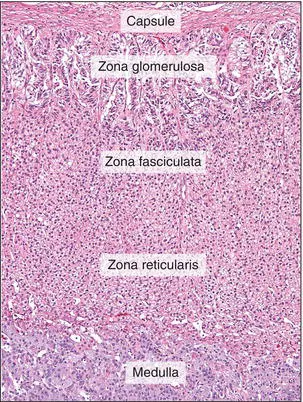

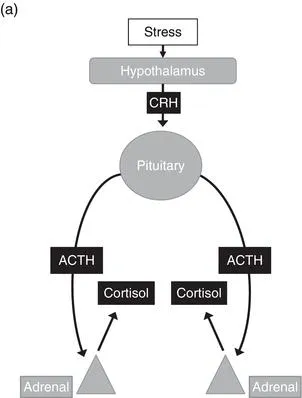

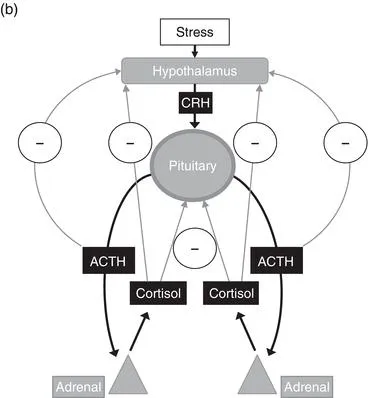

I. Pathogenesis

II. Signalment

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1: Hypoadrenocorticism in Dogs

- CHAPTER 2: Hypoadrenocorticism in Cats

- CHAPTER 3: Hypoadrenocorticism in Other Species

- CHAPTER 4: Critical Illness-Related Corticosteroid Insufficiency (Previously Known as Relative Adrenal Insufficiency)

- CHAPTER 5: Hyperadrenocorticism in Dogs

- CHAPTER 6: Primary Functioning Adrenal Tumors Producing Signs Similar to Hyperadrenocorticism Including Atypical Syndromes in Dogs

- CHAPTER 7: Hyperadrenocorticism in Cats

- CHAPTER 8: Primary Functioning Adrenal Tumors Producing Signs Similar to Hyperadrenocorticism Including AtypicalSyndromes in Cats

- CHAPTER 9: Hyperadrenocorticism in Ferrets

- CHAPTER 10: Hyperadrenocorticism and Primary Functioning Adrenal Tumors inOther Species (Excluding Horses and Ferrets)

- CHAPTER 11: Hyperadrenocorticism (Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction) in Horses

- CHAPTER 12: Primary Hyperaldosteronism

- CHAPTER 13: Pheochromocytoma in Dogs

- CHAPTER 14: Pheochromocytoma in Cats

- CHAPTER 15: Canine Diabetes Mellitus

- CHAPTER 16: Feline Diabetes Mellitus

- CHAPTER 17: Diabetes Mellitus in Other Species

- CHAPTER 18: Canine Diabetic Emergencies

- CHAPTER 19: Feline Diabetic Ketoacidosis

- CHAPTER 20: Equine Metabolic Syndrome/Insulin Resistance Syndrome in Horses

- CHAPTER 21: Insulinoma in Dogs

- CHAPTER 22: Insulinoma in Cats

- CHAPTER 23: Insulinomas in Other Species

- CHAPTER 24: Gastrinoma, Glucagonoma, andOther APUDomas

- CHAPTER 25: Hypothyroidism in Dogs

- CHAPTER 26: Hypothyroidism in Cats

- CHAPTER 27: Hypothyroidism in Other Species

- CHAPTER 28: Hyperthyroidism in Dogs

- CHAPTER 29: Hyperthyroidism in Cats

- CHAPTER 30: Hyperthyroidism/Thyroid Neoplasia in Other Species

- CHAPTER 31: Hypocalcemia in Dogs

- CHAPTER 32: Hypocalcemia in Cats

- CHAPTER 33: Hypocalcemia in Other Species

- CHAPTER 34: Hypercalcemia in Dogs

- CHAPTER 35: Hypercalcemia in Cats

- CHAPTER 36: Hypercalcemia in Other Species

- CHAPTER 37: Nutritional Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Reptiles

- CHAPTER 38: Hyposomatotropism in Dogs

- CHAPTER 39: Hyposomatotropism in Cats

- CHAPTER 40: Acromegaly in Dogs

- CHAPTER 41: Acromegaly in Cats

- CHAPTER 42: Diabetes Insipidus and Polyuria/Polydipsia in Dogs

- CHAPTER 43: Diabetes Insipidus in Cats

- CHAPTER 44: Hyponatremia, SIADH, andRenal Salt Wasting

- CHAPTER 45: Estrogen- and Androgen-Related Disorders

- CHAPTER 46: Progesterone and Prolactin-Related Disorders; Adrenal Dysfunction and Sex Hormones

- CHAPTER 47: Pathologic Reproductive Endocrinology in Other Species

- Index

- Advertisements