- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Richly illustrated, and featuring detailed descriptions of works by pivotal figures in the Italian Renaissance, this enlightening volume traces the development of art and architecture throughout the Italian peninsula in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

- A smart, elegant, and jargon-free analysis of the Italian Renaissance – what it was, what it means, and why we should study it

- Provides a sustained discussion of many great works of Renaissance art that will significantly enhance readers' understanding of the period

- Focuses on Renaissance art and architecture as it developed throughout the Italian peninsula, from Venice to Sicily

- Situates the Italian Renaissance in the wider context of the history of art

- Includes detailed interpretation of works by a host of pivotal Renaissance artists, both well and lesser known

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Italian Renaissance Art by Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Renaissance Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What a Difference a Hundred Years Makes

There is no such thing as “progress” in art. Unlike modern concepts of science, art cannot be “dated” or outmoded. One work of art is not more important because it was made after another. Nor does it make its predecessor obsolete. In fact, some of the most valuable works of art are some of the oldest known to us – a Sumerian statue, an Egyptian crown, a Greek tombstone, for example. So, we may ask, why does time matter: why do we study the history of art and not just “art”?

Time is not an enemy invented by the gods to confuse us. On the contrary, in the history of art it is our friend. By paying attention to it we can understand many things that might otherwise elude us. A work of art can, for example, be remarkable in the year that its features were invented, whereas the very same work of art copied a generation later may have less or little value. Even so, in the big picture of the history of art, one hundred years is not much. An ancient Egyptian temple, for example, might be dated within several hundred years, or even a thousand, because styles and materials did not change much in ancient Egypt. But in the Italian Renaissance, a hundred years is a stellar leap in the chronological ordering of artistic events. This is even more true when we take into account that time is colored by geographic locality, for in different places developments occur at different paces. When we think about such things we can more easily extract the significance of a work of art.

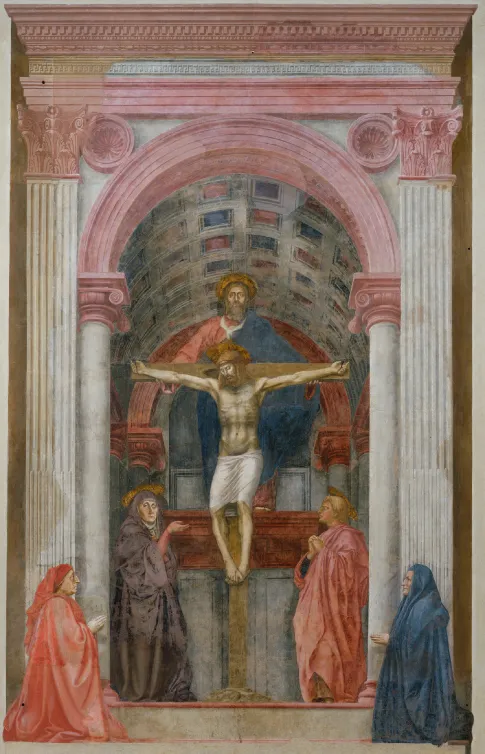

Both Masaccio’s Trinity (fig. 1.1) and Pontormo’s Deposition (fig. 1.2) were important commissions, about a hundred years apart, and both were painted for churches in Florence. Both represent the same subject, the dead Christ. Yet they are completely different.

Figure 1.1 Masaccio, Trinity. Sta. Maria Novella.

(Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY.)

Figure 1.2 Pontormo, Deposition, Florence, Sta. Felicità.

(Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY.)

The painting by Masaccio depicts the wounded and lifeless body of Christ hanging from a cross which is grasped from behind by the hands of God the Father. Christ is being mourned by two figures who stand below in the space of the picture and worshipped by two figures who kneel in front praying in what seems to be our space. One of the mourners looks out at us and gestures to us, inviting us to enter the picture and participate in the sorrow they feel. The other figures pray: they are us. The object of their attention is the mortal figure of Christ, who has expired after a long agony and tragic death. Though dead, Christ is victorious: for, standing behind him, God the Father enlarges the image of Christ so as to allow it to dominate the picture space. Christ is the center and the focal point. By dropping the floor out of our sight and articulating the receding coffers of the ceiling to assure that we are seeing it from below, the artist suggests to us that we are looking up with reverence and respect. Thus the eye ascends slowly to its ultimate destination in the center, the figure of Christ being displayed to us by God himself.

Above the center, a huge barrel vault is represented in perspective, ingeniously imagined for the first time in the history of painting. Its compartments diminish so that the fresco appears to be hollowed out of the actual wall it was painted on. It creates a chamber that defines and measures a space that is clearly structured and related to the space of the viewer. Inside the cube of space, the mourners stand on a platform; the worshippers kneel on the ground in a space of their own – their space is our space. A rational light enters the scene from our world, illuminating the fresco from the front and casting shadows behind the forms it defines. The colors illuminated by this light are earthy and naturalistic. Their chromatic accents convince us that the forms they describe really do exist and really do project. All the figures, including the divine ones of Christ and God the Father, are naturalistically formed. They behave in rational ways. Their actions, thoughts, and struggles are clear. They are ennobled figures participating in an ennobled drama.

Standing in front of the painting and riveted to its center, the viewer becomes an unseen participant in the painting. Taking into account this position in the forward center, the triangular arrangement of the painting’s figures is enlarged to form a pyramid whose fourth point is anchored by the viewer and symmetrically embraced by the architectural elements to either side. This is the first time in the history of art that such a geometrical scheme has defined the situation of a painting. Through the viewer’s participation in the pyramidal arrangement of the whole, human measure has, also for the first time, become the fundamental element of a painting. The unseen viewer thus becomes a yardstick for the conception of all the figures in the painting, human and divine, as well as of the architecture. Every part in this painting is conceived on the human scale and interlocked in a geometrical order that is indissoluble and exudes a profound calm. And so the contemplative character of this painting is based on a deliberately conceived scientific concept which results in a total harmonic equilibrium. Thus must this painting have stood out in an art world that was essentially medieval at the time of its conception. In this painting everything is clear; everything is sure.

Masaccio’s dead Christ, painted in 1427 when the artist was but 26 years old and shortly before his untimely death in the following year, leaves the viewer with no doubts on these matters.

In contrast, Pontormo’s work, painted in about 1527, presents us with a myriad of doubts. Though it also depicts the body of Christ, we cannot tell if Christ is dead, or alive, or asleep. We do not know the identities or the roles of the other figures in the painting, though we may assume that of the Madonna. We do not even know if some of the figures, especially those in the lower part of the painting, are men or angels. How these two figures can manage to carry the body of a grown man while on tip toes is a mystery. An arm that belongs to nobody reaches out from nowhere to touch the left hand of Christ. The head above Christ has no body because there is no room for any. Almost in vain, the viewer searches for the focus of the painting. Its center is an empty space, a hollow – home to a gnarl of convoluted, writhing, hands and distorted wrists which limpidly seek to move in dislocated gestures. Indeed, the eyes of participants and observer alike look away from, rather than towards, the center.

In this picture there is no triumph. Far from being inspirational, the wounds of Christ are absent; rather Christ appears to be experiencing a euphoric sleep. This sleep is a source of irresistible agonized ecstasy privately expressed by those around him. The artist has diverted the eyes of his figures so that only one of them looks at Christ, and she is passing out. The others twist and turn, like demented characters who are in search of a theme. A small man to the far right is physically and psychologically disconnected from all the others. This irrational combination of figures whose roles we cannot ascertain suggests an image far removed from triumph – that of total and complete despair.

In Pontormo’s painting everything is left vague. There is no architecture, no cross, no landscape, no space, no distance – in short, no nature. There is no reference to an actual place or to actual people. No boundaries exist. Elongated and incoherent, the androgynous bodies form an endlessly meandering pattern over a surface where one lone cloud has as much value as a human figure. Their scale is incomprehensible. If the Madonna were to stand, she would be far taller than any of the variously sized other figures. While she looks longingly at her son, he appears to have glided off her lap, a fact of which she is unaware. The figures are separated psychologically not only from each other, but also from the viewer. Their bodies are described, yet the surfaces of the bodies waver and vacillate, fluctuating in emptiness. Their owners do not comprehend physical strain, but only mental strain. Disinclined to be declamatory, they gesture hopelessly, like haunted phantoms, as they float before us in a world where there is no physical order but only environmental ambiguity. Instead of collaboration between the mind and the body there is emptiness; heads look away from what the arms are doing. The figures are distracted; unable to concentrate, their bodies are here while their minds are somewhere else.

The timeless frozen world of Pontormo’s figures is also described by its color: rather than the glowing light of day it is set in a grey, stony bluish light. The figures are all dressed in translucent colors – cool tones of rose pink, pale chartreuse, glowing mauve, shimmering orchid, beige green, mustard yellow, and powder blues. Color is modeled as though from nature, but nature is absent.1 Off-shade greens conflict with pale pinks, yellow greens with cranberry, pink areas cast orange shadows. Much of the emotionally disruptive impact the spectator suffers is due to the juxtaposition of opposed colors: through this method, Pontormo expresses the grief and emotional disturbance of his images. Only one figure is dressed in warm colors, and he remains isolated and bewildered in the far right.

Because the order of Pontormo’s painting is not determined by nature, the figures are allowed to act out their roles in individualistic ways that, since each figure is divorced from the others in the painting, result in the isolation of each. Each stares hauntingly out of the picture, into an empty space of his or her own. As a group they gesture hopelessly. Not one of them connects with the viewer. The viewer is unnecessary in this rarified world where figures are made of soft, flexible matter that disregards the necessity for organic infrastructure; where cloth and flesh fade into one another; where solids are treated like liquids; and where surging undulations of drapery billow and defy the laws of gravity.

Whereas in Masaccio’s painting the geometry tells the story, in Pontormo’s it is the colors that do so. And the story is in each case very different. Masaccio’s great invention, in a world still medieval and attached to irrational color and space, was rational color and space. Pontormo’s great invention, by contrast, in a world that valued rational color and space, was irrational color and space. For Masaccio the emotion of the painted surface exists in discovering the laws of nature, while for Pontormo emotions are expressed by breaking the laws of nature. All the elements that were clear in Masaccio’s painting in 1427 have become unclear in Pontormo’s work of 15...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Italian Renaissance Art: Understanding Its Meaning

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Frontispiece: Map of places mentioned

- Introduction: The Renaissance as an Idea Rather Than a Period

- 1 What a Difference a Hundred Years Makes

- 2 How It All Started: Florence and Umbria

- 3 What Happened Next in Florence

- 4 Searching for the Renaissance (1): Siena and Southward to Sicily

- 5 Searching for the Renaissance (2): From Northern Italy Back to Umbria

- 6 The Triumph of the Intellectual Avant-Garde: The High Renaissance

- 7 Some Other Artists of the High Renaissance

- 8 The Swan Song of Renaissance Art

- 9 The Break and the New Avant-Garde: Early Mannerism

- 10 What Was the Italian Renaissance? Conclusions in the Bigger Picture

- Appendix A: Artists Mentioned

- Appendix B: Some Suggested Readings

- Index