- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Organised into four sections, this text discusses the organisation of the living world.

- Links Ecology, Biodiversity and Biogeography

- Bridges modern and conventional Ecology

- Builds sequentially from the concept and importance of species, through patterns of diversity to help consider global patterns of biogeography

- Uses real data sets to help train in essential skills

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Natural Systems by Markus Eichhorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: defining nature

1.1 How little we know

Understanding the organisation of nature has never been so important. The UN declared 2010 to be International Year of Biodiversity in advance of a meeting in Nagoya to discuss the Convention on Biological Diversity. Back in April 2002 the member countries had pledged

…to achieve by 2010 a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national level as a contribution to poverty alleviation and to the benefit of all life on Earth.1

It is safe to say that this target was not met; if anything the rate of extinctions increased over this time period (Butchart et al., 2010), and the continued trajectory is not promising. But was it ever an achievable goal? Problems with the statement include the very definition of biodiversity itself—what should we be counting, how do we go about it, and when will we know that the trend is reversing? How can we begin to collect the necessary information when fewer than 14% of all species have been formally identified (Mora et al., 2011)? A major theme of this book involves trying to answer these questions.

The concatenation of linked issues facing humanity, which include overpopulation, global climate change and an ongoing mass extinction (May, 2010), has prompted some to suggest that the only future for humanity is to leave the planet and take to the stars. It has long been a trope of science fiction that natural systems could be exported beyond Earth's atmosphere. Such a bold aspiration poses immense technical challenges, but these are at least equalled by the ecological problems. Is such an achievement—or salvation—within our capabilities?

The ultimate test of our understanding of natural systems is whether we are able to construct them ourselves. This was first attempted on a realistic scale by the Biosphere 2 project (Biosphere 1 being the Earth). A sealed glasshouse was constructed in Arizona between 1987 and 1991 covering 1.27 ha; it remains the largest ever constructed. It originally contained a series of different habitats along with agricultural land. The total cost of the project was $200 million (around $0.5 billion at today's value). Two attempts were made to completely seal groups of scientists inside. One of the major problems turned out to be atmospheric control; carbon dioxide levels fluctuated wildly both daily and seasonally, and oxygen levels fell by 30% over the first 16 months, leading to an injection of oxygen on medical grounds. All pollinator species and most vertebrates went extinct, while pests such as cockroaches became superabundant. Much was learnt from these studies, but in terms of the grand ambition—conducting a pilot study for future space stations—it must be considered an abject failure. No one has tried again since the last mission was abandoned in 1994. For all our knowledge and understanding, we still cannot build a closed, functioning ecosystem.

1.2 Pressing questions

There are several profound gaps in our understanding of the natural world. As in any branch of science, asking the questions can seem deceptively simple, but arriving at the answers is more challenging. This book attempts to address the following:

- What governs the number of species present in any one location?

- What determines the identity of these species?

- How do local and broad-scale ecological processes interact with one another?

In order to reach an appropriate level of understanding to tackle these questions, we must draw from a number of fields including diversity theory, community ecology, ecosystem functioning and biogeography.

1.3 The hierarchy of nature

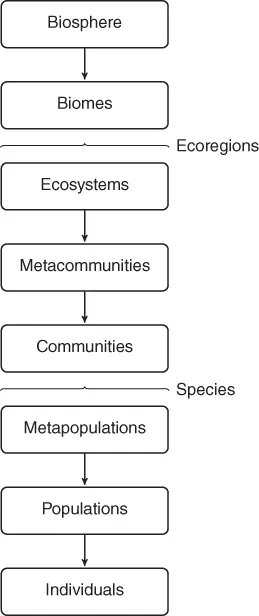

First it is important to identify the major scales of organisation in nature (Figure 1.1). Knowing the differences between these is essential. Each term has a very specific meaning and conflating concepts can lead to confusion. A crucial point is that processes which operate at one scale (e.g. the local community) might be irrelevant at another (e.g. the ecoregion). For example, competition is a central structuring force in explaining species interactions within a grassland but tells us little about species distributions on the scale of an entire continent.

Figure 1.1 The hierarchical organisation of life on Earth. Components are linked by arrows where each level is a spatially-nested element of that above. Biomes are divided into ecoregions which are spread across the globe; likewise communities are made up of species which are not exclusive to any single community.

Ecology begins with individuals, typically recognised as independent reproductive organisms. This definition is less simple to enforce than it sounds and can occasionally be arbitrary in its application. Colonial organisms such as sponges and bryozoans are composed of multiple individuals which depend on their membership of a single structure to reproduce; hence it is common to count the whole colony as an individual. In some social species, such as ants, most colony members are unable to reproduce but instead support the reproduction of a single queen. Here it would make most biological sense to count each colony as an individual, yet for practical reasons (ants are easier to find and count than their nests), it is more common to count the sterile workers and treat them as individuals, which is also a more reasonable means of estimating their wider ecological impacts. Even at the individual level we have to recognise that complications can arise.

One way of identifying an individual might be to say that it is the product of a single fertilisation event, known as a genet. This is fine for sexually reproducing organisms, but not for those which are asexual, where offspring are identical copies of their parent. In some cases both can live side by side. Strawberry plants can be grown from seed, each the result of the pollination of a single ovule in a flower. As they grow, however, they send out runners which develop their own roots and can detach to become separate plants. These are known as ramets—despite being genetically identical to their parent, they still compete for all the same resources. A patch of wild strawberries could contain any proportion of genets and ramets.

Individuals can be highly variable in their behaviour, physiology and genetics; these have profound implications for the dynamics of populations, which are collections of individuals of the same species linked by reproduction. Once again, defining a population is simpler than recognising one; it is difficult to determine where the boundaries of reproductive links are, and therefore for convenience we typically demarcate populations based on sensible habitat features rather than by assessing gene flow (e.g. the edge of a lake would mark the boundary for a single population of fish). In more recent ecological theory it has been recognised that populations are linked by dispersal of individuals into metapopulations which have their own higher-order dynamics (Hanski, 1999). In truth there is often a continuum between the two, though in cases where discrete units can be identified (e.g. islands), with a discontinuity in dispersal, the concept can be vital in appreciating how local and regional dynamics are connected.

In conventional ecological theory, the population size is the sum of all the actively (or potentially) reproducing individuals. This therefore excludes juveniles (eggs, larvae and young) and—perhaps more surprisingly—males, since they do not control the rate of reproduction. Here again the theoretical and the practical are not easily reconciled. Consider the moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita). It reproduces sexually, forming larvae which sink to the sea floor and form polyps. Normally these will wait for suitable conditions before budding to generate around 20 floating jellyfish. When the environment is unfavourable, however, these polyps can instead choose to create new polyps or form resilient long-lasting cysts. Apparent explosions in jellyfish abundance occur as soon as conditions allow. A species like this foils all our idealised concepts of how we determine population size.

The sum of all individuals makes up the totality of a species. The precise definition used to decide where the boundaries lie between species has further implications for how we interpret patterns in nature. This is the subject of the next chapter and the starting point for thinking about natural systems.

When multiple species occur in a single location, and show stabilitythrough time, it is referred to as a community. Typically these species are linked by feeding relationships into a food web and through interactions including competition, mutualism and parasitism. Interpreting the dynamics of any single population requires an understanding of these linkages. In an analogous fashion to populations, communities can be joined together in metacommunities, which are networks of communities connected by the dispersal of species (Holyoak et al., 2005). This is a relatively recent concept in ecology but has great explanatory power when linking the processes occurring at small scales to those on a regional leve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1: Introduction: defining nature

- Part I: Species

- Part II: Diversity

- Part III: Communities

- Part IV: Biogeography

- Appendix A: Diversity analysis case study: Butterfly conservation in the Rocky Mountains

- Glossary

- Index

- End User License Agreement