![]()

Section 1

General Fertilization Concepts

![]()

Chapter 1

Nutrient Cycling

Claude E. Boyd

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Pond fertilization is the practice of adding plant nutrients to pond water. These additions enhance phytoplankton growth at the food web base, eventually culminating in fish and other aquaculture species. This task is accomplished by applying either chemical fertilizer or organic matter such as animal dung and other agricultural wastes. Chemical fertilizers dissolve in pond water increasing nutrient concentrations and stimulating phytoplankton growth. Organic matter is decomposed by saprophytic microorganisms with mineralization of inorganic nutrients for use by phytoplankton. Organic matter also may be a direct organic nutrient source for invertebrate fish food organisms, and some fish species feed directly on manure particles. Pond treatment with organic matter actually represents combined fertilization and feeding.

In this chapter, only inorganic nutrients resulting from chemical fertilizer and organic matter applications to ponds will be considered. These nutrients participate in complex biogeochemical cycles, and effective pond fertilization programs must consider how these cycles influence fertilizer nutrient availability to phytoplankton.

1.2 PLANT NUTRIENTS

Green plants require numerous inorganic nutrients in relatively large amounts (macronutrients) or in fairly small quantities (micronutrients) (Pais and Jones 1997). Macronutrients are carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, calcium, magnesium, and potassium. Sodium is a macronutrient for some species, and diatoms need a relatively large silicon amount. The common micronutrients are iron, manganese, zinc, copper, and molybdenum—some plants also require one or more other elements such as chloride, boron, and cobalt.

Carbon dioxide enters water from the atmosphere and from microbial organic matter decomposition. Hydrogen and oxygen are available from water. The major nitrogen source is organic nitrogen mineralization to ammonia nitrogen during microbial organic matter decomposition. Other nutrients are derived from mineral dissolution. Sources of these nutrients may be runoff entering ponds following contact with minerals in catchment soils, spring or well water contacting minerals in aquifer formations, and mineral dissolution in pond bottom soil. Seawater and estuarine water used in coastal ponds have high major cation concentrations.

According to Liebig’s Law of the Minimum (Odum 1975), plant growth is limited by the nutrient present in shortest supply relative to its need by phytoplankton. Phytoplankton and other aquatic plants are limited most commonly by inadequate phosphorus and nitrogen, but in waters of either low or high alkalinity, a carbon dioxide shortage may limit plant growth (Boyd 1972). In seawater, it is suspected that low iron and manganese concentrations may also limit phytoplankton growth (Nadis 1998).

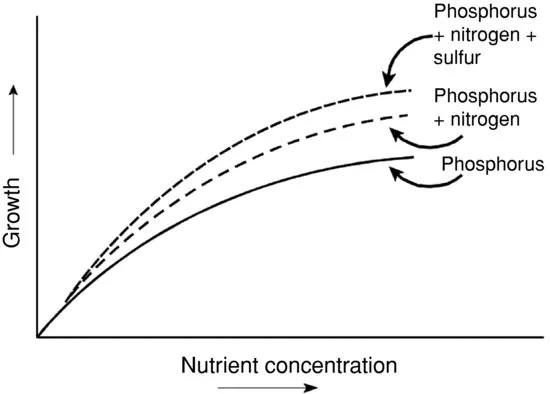

Liebig’s Law does not imply that a single nutrient controls phytoplankton growth. To illustrate, suppose, phosphorus is the most limiting nutrient in a pond to which a phosphorus fertilizer application is made. After fertilizer application, phytoplankton abundance will increase in response to the greater phosphorus concentration until some other nutrient becomes limiting. Remaining added phosphorus will not elicit a growth response until more second limiting nutrient is applied. Adding more second limiting nutrient could lead to a third nutrient becoming limiting (Polisini et al. 1970). Thus, Liebig’s Law applies to multiple limiting nutrients (Fig. 1.1).

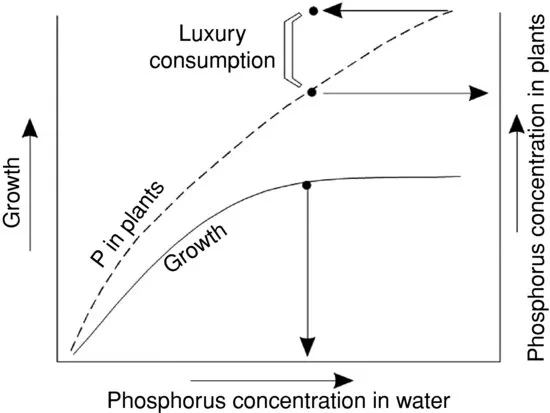

Plant response to nutrients also may be confounded by luxury consumption (Gerloff and Skoog 1954, 1957). In luxury consumption, plants absorb more nutrient than necessary for maximum growth. The excess nutrient is stored in plant cells for later use, or in the case of phytoplankton cells, the nutrient may be passed on to succeeding generations when cells divide. The luxury consumption concept is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

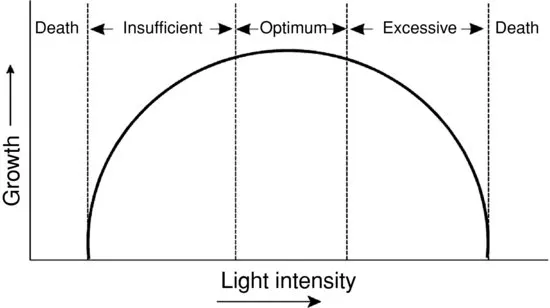

Liebig’s Law was expanded by Shelford’s Law of Tolerance (Odum 1975). This law states there may be either too little or too much nutrient or other environmental factors as illustrated in Figure 1.3 for light. In the case of nutrients, some such as copper can be limiting to phytoplankton growth at low concentrations, but be toxic to phytoplankton at higher concentrations (Boyd and Tucker 1998). In fact, copper sulfate is probably the most common algicide in use today. Most nutrients can be toxic at high concentration, but in ponds, nutrient concentrations seldom reach toxic levels.

Factors other than nutrients also can limit phytoplankton growth. Some examples are inadequate light because of cloudy weather or excessive pond turbidity, low temperature, and low pH.

Water analyses may be used to measure nutrient concentrations, but it is difficult to determine which nutrients limit phytoplankton growth. In lake eutrophication studies, water samples were filtered to remove phytoplankton, aliquots were placed in flasks, nutrients were added singly and in various combinations to flasks, flasks were inoculated with a planktonic algal species, and after a few days, the algal abundance was more in the flasks compared with algal abundance in a flask to which no nutrients were added (Miller et al. 1974; Golterman 1975). Because of its complexity, this procedure is seldom suitable for determining nutrient requirements for individual ponds, but it could be used in a study to assess nutrient limitations in ponds across a region. Results of such a study would reveal the likely limiting nutrients for ponds in the region.

Experience with pond fertilization in many countries suggests nitrogen and phosphorus are the only two nutrients normally needed in fertilizers for freshwater ponds (Mortimer 1954; Hepher 1962; Hickling 1962; Boyd and Tucker 1998). These two nutrients also are most commonly used in fertilizing ponds filled with brackish water or seawater. However, micronutrients are sometimes included in fertilizers for shrimp ponds. Moreover, because they think diatoms are a superior natural food for shrimp, farmers in Central and South America often apply silicate fertilizer such as calcium silicate to shrimp ponds.

There is a widespread idea, phosphorus is not as important in brackish water and seawater ponds as in freshwater ponds. This has led to frequent use of wide N:P ratios in fertilizers for shrimp ponds in Central and South America. However, a recent review (Elser et al. 2007), suggested nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems are similar.

Another common idea about nutrient ratios in fertilizer originates in the observation of the average molecular ratio of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in marine phytoplankton of 106:16:1 (weight ratio = 41:7.2:1)—the Redfield ratio (Redfield 1934). Brzezinski (1985) suggested including silicon in the Redfield ratio—the molecular ratio C:Si:N:P for marine phytoplankton is 106:15:16:1 (weight ratio = 41:13.6:7.2:1). The Redfield ratio suggests phytoplankton need nitrogen and phosphorus in roughly a 7:1 ratio, and it is often recommended that pond fertilizers for freshwater and saline water ponds should contain nitrogen and phosphorus in this ratio. However, several factors influence the fate of nitrogen and phosphorus added to ponds in fertilizers, and adding nitrogen and phosphorus in fertilizers according to the Redfield ratio does not assure the same ratio of the two nutrients in pond water.

1.2.1 Phosphorus

FORMS IN WATER

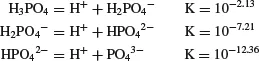

There are several phosphorus forms in water; the most common are: (1) soluble inorganic phosphorus, (2) soluble organic phosphorus, (3) phosphorus in particulate organic matter (living plankton or detritus), and (4) phosphorus adsorbed on suspended mineral particles. Soluble inorganic phosphorus is an ionization product of orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4):

Pond water pH is usually between 6 and 9, and the most common soluble inorganic phosphorus forms are H2PO4− and HPO4−. These two ion proportions are equal at pH 7.21—at lower pH, H2PO4− is dominant and at higher pH, HPO4− is more abundant.

All soluble phosphorus in water is not in inorganic form; some associated with soluble organic compounds. The most common way of estimat...