![]()

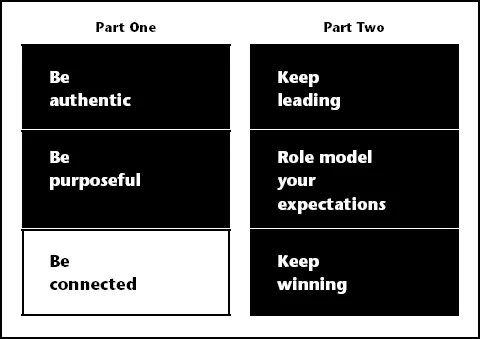

Part One

Unleashing the Power of Me

How to Make Yourself and the People Around You Stronger

Part One of this book discusses how to make yourself and the people around you stronger. Its three major change-leadership takeaways are: be authentic, be purposeful and be connected.

The first change-leadership takeaway is to be authentic. Chapter One focuses on valuing integrity, knowing who you are and knowing what you want to do with your life.

The second change-leadership takeaway is to be purposeful. This is the subject of Chapter Two. Once you know what you want, develop clear goals, venture out, build energy and renew yourself periodically.

The third change-leadership takeaway, as discussed in Chapter Three, is to be connected, which moves beyond being connected with yourself to being connected with people around you and with your environment.

![]()

Chapter 1

Be Authentic

The first change-leadership takeaway is to be authentic. It begins with valuing integrity, knowing who you are and knowing what to do with your life.

Look in the Mirror

When, in 1974, I moved from northern New Jersey to work at the Dorsey Laboratories Company in Lincoln, Nebraska (about as far from where I grew up as anywhere in the world), I understood how I might be perceived—as a foreigner with an accent in a suit sent from corporate. I was also only the second senior Sandoz executive to show up at this fiercely independent company, which had been taken over by Sandoz seven years earlier. Acknowledging that there would be all sorts of reasons for people to resent or be suspicious of me, I resolved to show them what I believed to be the real me—a down-to-earth person who wanted to make a difference.

Noreen and I acculturated with ease. Our positive attitudes made living in Nebraska enjoyable. We appreciated the warmth and hospitality of the new friends we made. We even became Cornhuskers fans and took in several home games, which were always amid a sea of red from the clothing of the enthusiastic fans chanting, “Go Big Red!”

“ ” At the office, I focused on listening, learning and making a difference. Within weeks, I knew I was gaining traction. I was getting invited in on important projects, such as the company's first five-year plan, and was soon promoted to the Operations Committee, Dorsey's Team at the Top that ran the company.

It was at Dorsey that I realized the collective teamwork and role modeling by the Team at the Top is critical as part of shaping a culture. That is why my Playbook uses this term repeatedly rather than conventional terms such as “Corporate Management.”

I kept getting promoted every year or two until I became the top commercial person at Dorsey. Then, while in my mid-30s, I accepted the opportunity to run a country operation for Sandoz as the local CEO. At my farewell dinner in June 1980, I received a plaque from the Operations Committee that described the philosophy I follow and carry with me to this day: “Success begins by reinventing oneself—via self-awareness, self-knowledge, and self-development.”

I had started developing my Playbook even before I went to business school, and now I was using and refining it—always starting with having a positive attitude (described in more detail later in the book). Building strength begins with having the courage to look into the mirror and to be brutally honest about what you see. You need to look in the mirror in order to recognize how people perceive you, so that you can then decide how to present yourself as you truly are. Positive transformation requires you to ask yourself the following questions: Who am I? What do I want? How am I doing? How am I really doing? How can I improve?

Learning self-truths via self-interrogation builds personal strength, which is necessary for building strength in others and for building team strength.

Use Mirrors to Tell the Truth

In a crisis, getting people to honestly see themselves can help turn around a game that is going badly for the home team. Going into the crisis at Schering-Plough (SGP) in 2003, I wanted to do something to show our people that we were all in this together—that only through their efforts could Schering-Plough be saved.

Brent Saunders, whom I brought in as head of compliance, had mirrors mounted at principal sites around the company. (Brent later became CEO of Bausch + Lomb). The idea was to start changing the mindset of our people. Since the company was in serious hot water with federal investigators for a variety of compliance issues, one goal of the mirrors was a practical one: to convince people to alert us to issues we should know about. There was a telephone number posted just under the mirror so that people knew whom to call if they had a question on compliance, suspected wrongdoing or knew of even unintentional violations.

We were encouraging people to do the right thing, but the purpose of the mirrors was much more. At companies in crisis, people tend to feel victimized and send negative energy to the people around them. We wanted our people, especially our frontline people, to take ownership of both the problems and the solutions. We wanted people to see themselves as part of the answer, as opposed to looking at others. We wanted them to develop productive attitudes.

We hoped the person in the mirror staring back would say, “If you see bad things happening, you are responsible for doing something about them. If you see good things happening, recognize them too.”

Self-honesty is an essential authenticity strength.

Know Who You are not

Sometimes looking in the mirror can help you recognize your limitations. In 1991 I was heading up Wyeth Domestic and Wyeth R&D (research and development), and one of the tough calls I made was in the leadership of the R&D division. Productivity, especially in the D (development) area, had not kept up with the best-performing companies. We had a big hole in our late-stage new-product pipeline. In trying to replace the exited R&D chief, I flirted with some radical thoughts. I was considering breaking up Wyeth's R&D and having both research and development report to me directly. This way, I could focus on the development operations directly.

Bob Essner worked for me as head of commercial. (Bob later became chairman and CEO of Wyeth.) He had taken a chance on me by being the first to join me in 1989 at Wyeth from Sandoz U.S. I asked Bob for his opinion about my idea of taking direct control of both research and development. He responded with a question: “Are you comfortable being head of R&D?” This subtle question made me realize what Bob already knew—I was not an “R&D guy.” Instead, I hired Bob Levy, MD, a world-renowned medical research leader, to head both R and D. He thrived in that position, and helped us build the strongest pipeline in Wyeth's history.

Another “know who you are not” leadership style I learned was to rely on the functional and technical experts to do their jobs. I didn't hesitate to pressure-test where I felt the need—but in the end, I wanted them to own their decisions.

Strong executives at every level of a company have mature and attuned attitudes that enable them to ask those they trust the tough questions about their abilities and their ideas—and to listen even if it isn't what they want to hear.

External feedback is important. Strong leaders must build a safe environment in which they can receive honest feedback from those around them. Besides recognizing your strengths, it is important to know when you need help from smart people. I know iconic CEOs who got derailed because they did not mitigate their own weaknesses with “A-players.” I have always tried to have strong players on my team, whose strengths obviated weaknesses and whose skills were complementary to mine and the other players'. I have also tried to have sounding boards and advisers on various subjects both within and outside the companies where I work, and outside people who could be even more objective. Having people around you who become the yangs to your yin, who help you keep your feet on the ground, becomes even more important the higher up you go in an organization.

The higher up we go in the organization, the more we get work done through other people. This means not only building trust with the people who will execute our decisions, but also a willingness to let go of the control that we may have had as successful individual contributors.

We may be fiercely proud of our own accomplishments, but, as leaders, we take pride in the accomplishments of others.

By knowing who you are not, you can offset your weaknesses.

Know Who You are

In addition to knowing who you are not, it is important to know who you are. I learned early in my career that I had a passion for and an ability to drive product innovation and global product launches. At Dorsey in the 1970s, I volunteered with corporate to launch a new antihistamine allergy medicine, Tavist. This medicine had already been launched in Europe. Even though the FDA had approved the product, Tavist had sat on the shelf for more than a year at Dorsey's then-larger sister division, Sandoz, because the Sandoz product-management group felt it was too difficult to launch. I got Dorsey Product Management busy with Tavist—but I also dug in as a “product driver.” The creative sessions built energy and growing conviction. We launched Tavist within six months of it being assigned to us. Tavist sales and profits in the United States soon surpassed those in other territories. Corporate headquarters in Basel, Switzerland, was so surprised with our success that the CEO, Dr. Marc Moret, asked me to be a special speaker on the Tavist story at the company's centennial celebration in Basel in the fall of 1986.

Some important questions to ask yourself are: Do I have the natural talent to excel in the job to which I am aspiring? Am I willing to fail? Am I willing to be relentless in the face of disappointments? Where you are not sure about your abilities, my perspective has been that you should have a bias toward “I can do it.” Believing in yourself makes you more likely to succeed.

You should try to find your hidden strengths, and then lead from them.

Make Business Integrity a Competitive Edge

Business integrity is a better working model than ethics or morality. The latter two are colored by the lens of the beholder, which sometimes reflects local religion or culture in a judgmental and divisive way. Business integrity is universal.

I learned from my parents that reputation and trust are critical. My dad retired in 1969. In 1976, the prime minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, asked him to come out of retirement to be Pakistan's ambassador to India, and to reopen the embassy, which had closed after the 1971 war. Prime Minister Bhutto told my father that he was choosing him knowing that he did not belong to his political party, but knowing that my father's whistle-clean reputation would help him gain rapid acceptance by India's prime minister, Indira Gandhi. I saw my dad succeed as a leader in his field because he earned trust.

The Catholic schools I went to embedded in me the values of diversity of thought, self-learning and doing good to others. I remember two booklets that were a part of our curriculum, both of which made a lasting impression on me. One was called Moral Science, and the other, Hints on Politeness. From them I learned that all human beings are special because they have intellect, memory, will and conscience. I learned that there were crosscutting basic values, such as the Golden Rule, that bring people together.

The fundamental premise is that we start life being morally equal—regardless of the family, the religion or the country we are born into. Through experience we refine our awareness of what is right or wrong until we become responsible for our own integrity. As CEO, I worked to develop a common language and understanding of business integrity that could span countries, cultures and religions. After my arrival at SGP, when the company was in serious hot water with the Department of Justice, one of my main messages at the first global town hall meeting in April 2003 was, “Let's look to business integrity as a way to differentiate ourselves by earning trust.”

Business integrity was commonly understood—whether we were in Kuala Lumpur, or Nanjing, or Prague, or Berlin, or New York, or São Paulo. The strong culture we developed made it possible to reenter into “compliance-challenged” countries like South Korea and Brazil, and to grow fast with our local operations there. SGP's Business Integrity Program became a learning center for other much larger companies.

Business integrity also means not playing favorites—even when we like someone more than others. Fairness builds trust. As CEO, I tried to be impartial not only on business matters, but also on social matters (such as not singling out any Level 2 colleagues for golf or card games or social trips).

All of us at one time or another, in both our careers and our private lives, will be confronted with decisions that will be guided by our own view of “doing the right thing.” Business integrity will allow us to sleep well at night.

In the spring of 1997, I had already decided to leave Wyeth (WYE) to take the CEO job at Pharmacia & Upjohn (PNU) when Ulf Wiinberg, a global executive who we inherited as a result of the American Cyanamid acquisition ...