- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Clinical Nutrition

About this book

This second edition of Clinical Nutrition, in the acclaimed textbook series by the Nutrition Society, has been revised and updated in order to:

- Provide students with the required scientific basis in nutrition, in the context of a systems and health approach.

- Enable teachers and students to explore the core principles of nutrition and to apply these throughout their training to foster critical thinking at all times. Each chapter identifies the key areas of knowledge that must be understood and also the key points of critical thought that must accompany the acquisition of this knowledge.

- Are fully peer reviewed to ensure completeness and clarity of content, as well as to ensure that each book takes a global perspective and is applicable for use by nutritionists and on nutrition courses throughout the world.

Ground breaking in scope and approach, with an additional chapter on nutritional screening and a student companion website, this second edition is designed for use on nutrition courses throughout the world and is intended for those with an interest in nutrition in a clinical setting. Covering the scientific basis underlying nutritional support, medical ethics and nutritional counselling, it focuses solely on the sick and metabolically compromised patient, dealing with clinical nutrition on a system by system basis making the information more accessible to the students.

This is an essential purchase for students of nutrition and dietetics, and also for those students who major in other subjects that have a nutrition component, such as food science, medicine, pharmacy and nursing. Professionals in nutrition, dietetics, food sciences, medicine, health sciences and many related areas will also find this an important resource.

Libraries in universities, medical schools and establishments teaching and researching in the area of nutrition will find Clinical Nutrition a valuable addition to their shelves.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Principles of Clinical Nutrition: Contrasting the Practice of Nutrition in Health and Disease

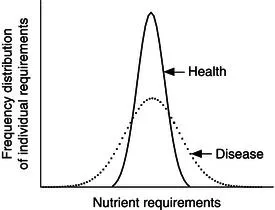

- To understand how to best meet the nutritional needs of an individual, the distinction between physiology in health and pathophysiology in disease needs to be carefully considered.

- For some groups of patients, the requirements are higher than those in health, while for other groups of patients they are lower. If recommendations for healthy individuals are applied to patients with certain types of disease, they may produce harm.

- In health, only the oral route is used to provide nutrients to the body. In clinical practice, other routes can be used. The use of the intravenous route for feeding raises a number of new issues.

- Alterations in nutritional therapy during the course of an acute disease may occur because the underlying disease has produced new complications or because it has resolved. Similarly, in more chronic conditions there is a need to review the diet at regular intervals.

1.1 Introduction

1.2 The spectrum of nutritional problems

| Adverse effect | Consequence | |

| Physical | ||

| Impaired immune responses | Predisposes to infection | |

| Reduced muscle strength and fatigue | Inactivity, inability to work effectively, and poor self-care. Abnormal muscle (or neuromuscular) function may also predispose to falls or other accidents | |

| Reduced respiratory muscle strength | Poor cough pressure, predisposing to and delaying recovery from chest infection | |

| Inactivity, especially in bed-bound patient | Predisposes to pressure, sores, and thromboembolism | |

| Impaired thermoregulation | Hypothermia, especially in the elderly | |

| Impaired wound-healing | Failure of fistulae to close, un-united fractures, increased risk of wound infection resulting in prolonged recovery from illness, increased length of hospital stay, and delayed return to work | |

| Foetal and infant programming | Predisposes to common chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and diabetes in adult life | |

| Growth failure | Stunting, delayed sexual development, and reduced muscle mass and strength | |

| Psychosocial | ||

| Impaired psychosocial function | Even when uncomplicated by disease, undernutrition causes apathy, depression, self-neglect, hypochondriasis, loss of libido, and deterioration in social interactions. It also affects personality and impairs mother–child bonding | |

1.3 Nutritional requirements

Effect of disease and nutritional status

Fluid and electrolytes

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Nutrition Society Textbook Series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Series Foreword

- Preface

- First Edition Acknowledgements

- 1 Principles of Clinical Nutrition: Contrasting the Practice of Nutrition in Health and Disease

- 2 Nutritional Screening and Assessment

- 3 Water and Electrolytes

- 4 Over-nutrition

- 5 Under-nutrition

- 6 Metabolic Disorders

- 7 Eating Disorders

- 8 Adverse Reactions to Foods

- 9 Nutritional Support

- 10 Ethics and Nutrition

- 11 The Gastrointestinal Tract

- 12 Nutrition in Liver Disease

- 13 Nutrition and the Pancreas

- 14 The Kidney

- 15 Nutritional and Metabolic Support in Haematological Malignancies and Haematopoietic Stem-cell Transplantation

- 16 The Lung

- 17 Nutrition and Immune and Inflammatory Systems

- 18 The Heart and Blood Vessels

- 19 Nutritional Aspects of Disease Affecting the Skeleton

- 20 Nutrition in Surgery and Trauma

- 21 Infectious Diseases

- 22 Nutritional Support in Patients with Cancer

- 23 Paediatric Nutrition

- 24 Cystic Fibrosis

- 25 Illustrative Cases

- Index

- Access to Companion Site