eBook - ePub

The Science of Intimate Relationships

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Science of Intimate Relationships

About this book

The Science of Intimate Relationships represents the first interdisciplinary approach to the latest scientific findings relating to human sexual relationships.

- Offers an unusual degree of integration across topics, which include intimate relationships in terms of both mind and body; bonding from infancy to adulthood; selecting mates; love; communication and interaction; sex; passion; relationship dissolution; and more

- Summarizes the links among human nature, culture, and intimate relationships

- Presents and integrates the latest findings in the fields of social psychology, evolutionary psychology, human sexuality, neuroscience and biology, developmental psychology, anthropology, and clinical psychology.

- Authored by four leading experts in the field

- Instructor materials are available at www.wiley.com/go/fletcher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Intimate Relationships by Garth J. O. Fletcher,Jeffry A. Simpson,Lorne Campbell,Nickola C. Overall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

1

The Science of Intimate Relationships

Focus of the book – domains of scientific study – interdisciplinary links – relationship mind and body – common sense and pop psychology – research methods – book overview – summary and conclusions

The emergence of a science of relationships represents a frontier – perhaps the last major frontier – in the study of humankind.

Berscheid and Peplau, 1983

The first known academic treatise on intimate relationships was Plato’s Symposium, written approximately 2300 years ago. In this historic document, Aristophanes tells a tale of a curious mythical being that is spherical in form with two complete sets of arms, legs, and genitalia. Because of the strength and speed of these creatures (they cartwheeled around on four arms and four legs), they posed a threat to the gods. Accordingly, Zeus split them in half and rearranged their genitals so that they were forced to embrace each other front on to have sexual relations. Some of the original beings had two sets of male genitalia, some had two sets of female genitalia, and some had one set of female and one set of male genitalia. Thus, procreation of the species was possible only by members of the original male–female creatures getting together. Possibly in deference to the sexual orientation of some of his audience (or to the tenor of that time), Aristophanes was quick to add that males who sought union with other males were “bold and manly,” whereas individuals who originated from the hermaphrodite creatures were adulterers or promiscuous women (Sayre, 1995, p. 106). Regardless of sexual orientation, the need for love is thus born of the longing to reunite with one’s long-lost other half and to achieve an ancient unity destroyed by the gods.

As this allegory suggests, individuals are alone and incomplete – an isolation that can be banished, or at least ameliorated, when humans pair off and experience the intimacy that can only be gained in a close, emotionally connected relationship. Such intimacy, the experience of reuniting with one’s long-lost other half, reaches its peak in parent–infant bonding and in the intimate high of romantic sexual relationships. But such intimacy is also experienced quite powerfully and deeply in platonic relationships, familial relationships, and in the long sunset of sexual relationships that have lost their passionate urgency and settled into a deep form of close companionship.

Just like Plato’s mythical beings, then, humans have a basic need to be accepted, appreciated, and cared for, and to reciprocate such attitudes and behaviors – in short, to love and to be loved (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). This is especially true for finding a sexual or romantic partner, a quest that can range from a one-night stand to seeking out a mate for life. Indeed, for most people the goal of forming a permanent, sexual liaison with another person is a pivotal goal in life in which a massive outlay of energy is invested.

In this textbook, we confine our attention largely to intimate relationships that are sexual or romantic rather than other types of relationships, such as parent–child relationships, platonic friendships, casual friendships, or co-worker relationships. Obviously, intimate relationships can be, and often are, influenced by these other types of relationships. When these connections are important or salient, we will address them. Moreover, we discuss certain categories of non-sexual relationships that are centrally related to adult intimate relationships, the most important being parent–child relationships. And we discuss both heterosexual and same-sex relationships, including their similarities and differences. Nevertheless, our attention is focused on heterosexual relationships, simply because most scientific research has investigated heterosexual relationships.

This introductory chapter sets the scene for the book by tracing the history of scientific work on relationships, dissecting what is true (and false) about common-sense and pop psychology, briefly discussing basic research methods in the field, and finally presenting a brief overview of the book’s contents. We have boldfaced all technical terms the first time they appear in each chapter of the book, and provide brief definitions of each term in the glossary at the end of the book.

The Science of Intimate Relationships: a Brief History and Analysis

As Plato’s symposium attests, humans have been theorizing about relationships for eons. This is not surprising, given the proclivity of humans to develop causal models and explanations, many of which are based on culturally shared understandings. Indeed, this is one hallmark of our species. Consistently, many of the topics covered in this book have been discussed in literature and plays hundreds of years before any rigorous scientific investigation of relationships appeared (think Homer, Shakespeare, and Jane Austen).

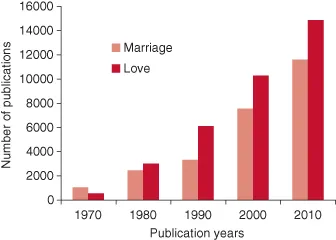

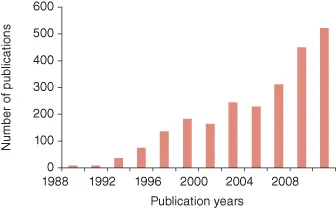

The first scientific forays into intimate relationships did not take place until the twentieth century. To give you some idea of the way in which scientific work has taken on tsunami proportions in relatively recent years, we used a popular academic data base – the Web of Science – to assess the number of publications in scientific journals devoted to the topic of relationships during the past 40 years (from 1970 to 2010). We first used the key words love and marriage. As shown in Figure 1.1, the number of publications has rapidly increased over the last 40 years. We then used the key words sexual or romantic relationships and looked at the number of publications in two-year periods from 1987 to 2010. The results, shown in Figure 1.2, also reveal a dramatic rise in publications, in this case from 12 in 1987/1988 to 520 in 2009/2010! These results show that nearly 70% of all the publications in scientific journals in these domains have appeared during the past 20 years, with about 40% of the articles published within the last decade.

Figure 1.1 Publications from 1970 to 2010 – love and marriage

Figure 1.2 Publications from 1988 to 2010 – sexual or romantic relationships

Domains of Study

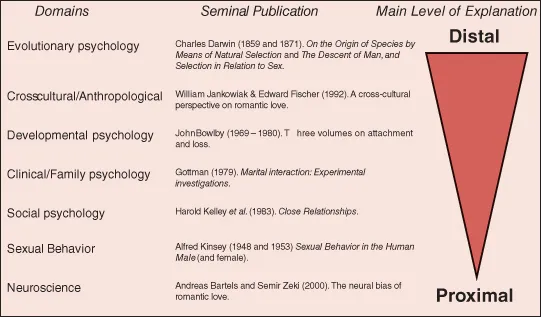

Publications relevant to romantic relationships have appeared across a diverse set of disciplines, including cross-cultural and anthropological studies, neuroscience, clinical and family psychology, developmental psychology, the science of sexual behavior, evolutionary psychology, and social and personality psychology. Figure 1.3 gives our take on the pioneering contributions in each field. Notably, all of the pioneering contributions were published in the second half of the twentiethcentury, with two stunning exceptions – two publications in the second half of the nineteenth century by Charles Darwin (more on Darwin later).

Figure 1.3 Major scientific domains studying sexual relationships from distal to proximal levels, along with seminal publications

Scientific approaches to the study of intimate relationships differ according to their goals and level of focus (see Figure 1.3). At the most general level, all human sciences have the same core aims – the explanation, prediction, and control of human behavior – although certain aims are sometimes emphasized depending on the particular approach. For example, clinical psychology emphasizes the prediction and control of relationship phenomena (especially relationship functioning, success, and stability), whereas social psychology and evolutionary psychology focus more on explanation.

Different approaches to the study of human relationships concentrate on different goals or questions, and, thus differ in their specific domain(s) of investigation. The study of social development, for example, is interested in understanding the development of bonding and attachment in childhood and how it relates to the development of intimate relationships across the life span (termed an ontogenetic approach). Evolutionary psychology is primarily concerned with understanding the evolutionary origins of human courting, sexual behavior, mate selection, parenting, and so forth. Thus, evolutionary psychology is primarily concerned with distal causes stemming from our remote evolutionary past in order to clarify current human behavioral, cognitive and emotional tendencies. Social psychology, in contrast, takes human dispositions (behavioral, cognitive, and emotional) as givens, and seeks to model the way in which our dispositions combine with external contingencies in our local environment to produce important behavior, social judgments, and emotions. Thus, social psychology offers much more fine-grained predictions and explanations of particular behaviors and cognitions that occur in specific situations (a proximal level) than does evolutionary psychology. Anthropological and cross-cultural approaches, on the other hand, focus on the way in which broad cultural and institutional contexts frame and guide the behavior of individuals and couples. Whereas social psychology tends to focus on the links between the individual and the dyadic relationship (e.g. how one person’s traits influence his or her partner and relationship outcomes), anthropological approaches tend to focus on connections between the couple (e.g. the rules and norms in relationship) and the wider culture in which the relationship is embedded.

An Example

A social psychological approach to understanding how people select mates might be to postulate a psychological model examining the importance that each partner places on particular characteristics (which will vary across individuals) are treated as cognitively stored standards, such as the perceived importance of finding an attractive and healthy mate. Individuals may then use these ideal standards to make choices between different potential mates or to evaluate how satisfied they are with their current mate. Resultant levels of satisfaction and relationship commitment, in turn, might then affect their own behavior, which might influence their partner’s behavior, resulting in the couple deciding to live together or break off the relationship. Thus, a social psychological model describes how cognitions, emotions, and behaviors interact (combine) within each person, and also how individuals in relationships communicate and influence each other (see Chapter 3). These models can be quite detailed, describing, as they do, a complex reality. Nevertheless, they deal only with a certain slice of what influences individuals and relationships at a given point in time, much of which operates at the proximal level (see above) rather than at the distal level emanating either from the remote evolutionary past or wider cultural forces.

Evolutionary psychology, on the other hand, asks important questions that social psychologists usually do not ask, such as why do people want mates who are attractive and healthy in the first place, or what are the origins of certain gender differences? (To avoid confusion, throughout the book we will use “gender” to refer to males versus females, and “sex” to refer to sexual intercourse or related behaviors and attitudes.) Answers for evolutionary psychologists often lie in the evolutionary history of humans, particularly in the adaptive advantages that should have accrued to our ancestors in ancestral environments if they were attracted to and chose certain kinds of mates, such as those who were relatively attractive and healthy.

Interdisciplinary Links

Scientists are increasingly working in an interdisciplinary fashion across all the domains shown in Figure 1.3. For example, social psychologists now are beginning to team up with evolutionary psychologists, developmental psychologists, and neuroscientists. Indeed, the whole field is becoming inter-disciplinary. Covering all these aspects in a single book is a tall order, and this cannot be accomplished in just one theory. Nevertheless, we attempt to address this broad and diverse body of work in this book (which makes this textbook unique among relationship texts). Our ecumenical strategy is based on our conviction that the most appropriate way to deal with the wide range of scientific approaches to relationships is in terms of a theory-knitting approach that focuses on different levels of explanation, ranging from proximal to distal causes. Different theories focus on different claims and deal with different parts of the very complex causal nexus that drives human behavior, including how people think, feel, and act in their intimate relationships. Accordingly, such theories are not necessarily in conflict; rather, they are often complementary, providing different ways to view and understand how different parts of the proverbial elephant can be combined (see the final chapter).

The Relation Between Mind and Body

In this book, we constantly move between biological and psychological processes. In Chapter 3, we cover the relationship mind. In Chapter 4, we discuss the relationship body and brain – which raises a longstanding debate in philosophy and science about the connection between minds and brains. The standard scientific stance, to which we adhere, is termed a materialist perspective. According to this view, the human mind and brain are one and the same, but they describe what is happening at different explanatory levels. A computer analogy clarifies this esoteric-sounding claim. The same computer software or program can be used to access and manipulate the stored information in the memory of two computers that differ in their internal hardware. A precise description of the two computers in terms of their electrical currents, stored electrical potentials, and hardware can also be provided. These latter descriptions, however, fail to give an adequate description and explanation of what the two computers actually do, which may be identical according to a higher-order description of how the information is processed in each computer (as specified by the programming software).

This computer analogy of the human brain and mind is irresistible – the mind is akin to a higher-order description of the brain’s hardware that details how information is stored, accessed, organized, and the specific functions it is used for. Both cognitive and social psychology operate at the software level. A neurological description of the brain, on the other hand, describes the hardware.

Interestingly, the common-sense psychology of human behavior is typically pitched at the software level of the brain. When we say that Mary believes that George is unhappy and buys him a gift to cheer him up, we are explaining Mary’s behavior in terms of information that is stored and acted upon in the same way that we explain how other intelligent systems work (such as non-human animals and computers). If anyone believes that human behavior can be described and interpreted without the spectacles of common-sense psychological theory, try to imagine someone baking a cake without perceiving their actions as intentional, or developing a good explanation for why George drove his car to Mary’s place without mentioning any of his goals, beliefs, wishes, wants, personality traits, abi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- About the Authors

- Preface: The Science of Intimate Relationships

- Part One: Introduction

- Part Two: The Relationship Animal

- Part Three: Beginning Relationships: Attachment and Mate Selection

- Part Four: Maintaining Relationships: the Psychology of Intimacy

- Part Five: Ending Relationships: the Causes and Consequences of Relationship Dissolution

- Part Six: Conclusion

- Glossary

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index