eBook - ePub

Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology

The Essentials

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology

The Essentials

About this book

Gastroenterologists require detailed knowledge regarding the anatomy of the GI system in order to understand the disturbances caused by diseases they diagnose and treat.

Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology will bring together the world's leading names to present a comprehensive overview of the anatomical and physiological features of the gastrointestinal tract.

Full colour and with excellent anatomical and clinical figures throughout, it will provide succinct, authoritative and didactic anatomic and physiologic information on all the key areas, including GI motility, hepatic structure, GI hormones, gastric secretion and absorption of nutrients.

GI trainees will enjoy the self-assessment MCQs, written to the level they will encounter during their Board exams, and the seasoned gastroenterologist will value it as a handy reference book and refresher for re-certification exams

Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology will bring together the world's leading names to present a comprehensive overview of the anatomical and physiological features of the gastrointestinal tract.

Full colour and with excellent anatomical and clinical figures throughout, it will provide succinct, authoritative and didactic anatomic and physiologic information on all the key areas, including GI motility, hepatic structure, GI hormones, gastric secretion and absorption of nutrients.

GI trainees will enjoy the self-assessment MCQs, written to the level they will encounter during their Board exams, and the seasoned gastroenterologist will value it as a handy reference book and refresher for re-certification exams

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology by John F. Reinus, Douglas Simon, John F. Reinus,Douglas Simon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gastroenterology & Hepatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Structure and innervation of hollow viscera

Laura D. Wood

Elizabeth A. Montgomery

Department of Pathology, Baltimore MD USA

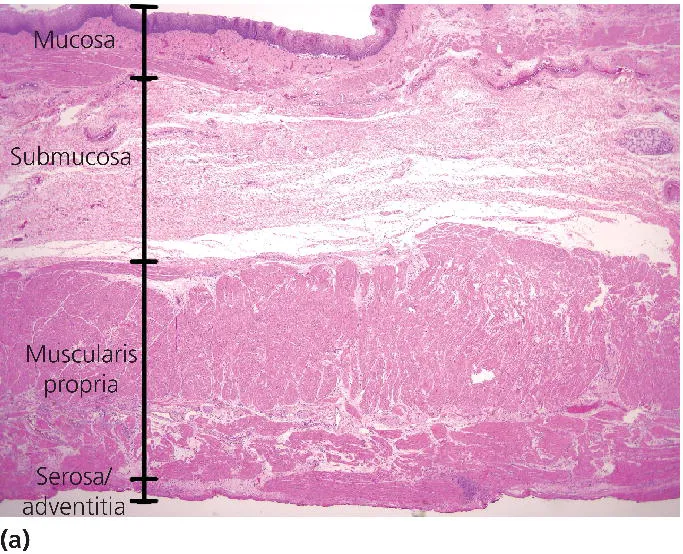

The tubular gastrointestinal (GI) tract consists of hollow organs composed of distinct tissue layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa or adventitia. The mucosa of each GI organ has a unique cellular structure, whereas the other layers are similar throughout the GI tract. Innervation of the hollow viscera consists of postsynaptic sympathetic and presynaptic parasympathetic neurons with parasympathetic ganglion cells present in the myenteric (Auerbach’s) and submucosal (Meissner’s) plexi. It is important to note that there is more lymphoid tissue (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) in the GI tract than there is in all the rest of the body combined.

The mucosa

The mucosa is the innermost layer of the GI tract; its function will be discussed in detail in the succeeding text. The mucosa has three components:

- The epithelium, which has protective and secretory or absorptive properties.

- The lamina propria, a loose connective tissue zone supporting the avascular epithelium. In the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine, but not the colorectum, the lamina propria has many lymphatics, allowing mucosal tumors to easily invade the lymphatics of the upper GI tract. In the upper GI tract, there are fewer immune cells (lymphoid and plasma cells) in the lamina propria than there are in the lamina propria of the small bowel and colon.

- The muscularis mucosae, a narrow double layer of inner circular and outer longitudinal smooth muscle separating the mucosa from the submucosa. The muscularis mucosae resembles the muscularis propria but in miniature.

The submucosa

The submucosa is composed of connective tissue and contains Meissner’s nerve plexus as well as large-caliber blood vessels.

The muscularis propria

The muscularis propria gives structural strength to the hollow viscera. It is composed of an inner circular and outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle. Between these layers is Auerbach’s nerve plexus.

Serosa or adventitia

The outermost layer of the GI tract is either a serosa or an adventitia. The latter is distinguished by its lack of a mesothelial membrane lining.

Parasympathetic ganglion cells are found in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s nerve plexi. The submucosal Meissner’s plexi also contain neuronal cell bodies of the intrinsic sympathetic nerve system that function on the local area of the gut. These are the neurons that have chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors. They synapse on both other ganglion cells and on muscle and secretory cells.

Esophagus

The esophagus is about 25 cm in length and consists of a cervical and upper-, mid-, and lower-thoracic segments. It is physiologically constricted by the cricoid cartilage, the aortic arch, the left atrium, and the diaphragm. The esophagus is unique among the hollow viscera in that it has skeletal (voluntary) muscle, which surrounds its upper portions. The vagus nerve provides the esophagus with parasympathetic innervation, whereas its sympathetic innervation is from the cervical and paravertebral ganglia.

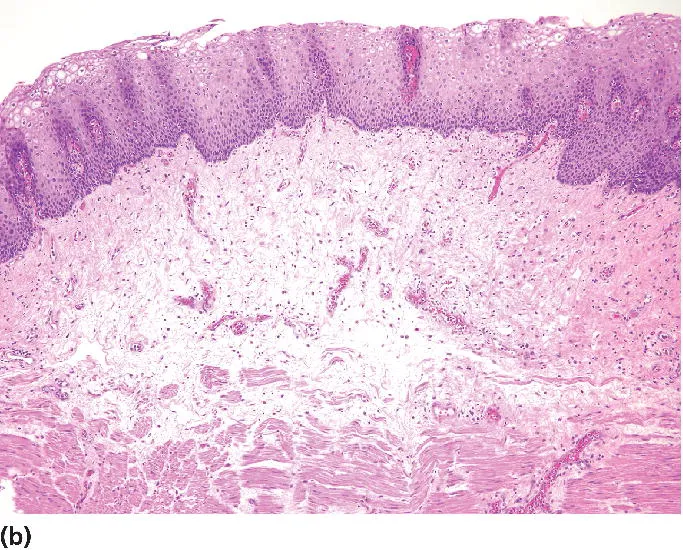

Histologically, the squamous mucosa of the esophagus is heaped up in folds (Figure 1.1a and b). The mitotically active basal layer matures completely into a surface layer containing tonofilaments within 10 days. The basal layer comprises about 15% of the esophageal epithelial thickness. The cells become flatter and more eosinophilic as they approach the surface. The normal esophageal epithelium lacks a granular layer (present in skin) and does not keratinize. A small number of T lymphocytes are normally present in the epithelium.

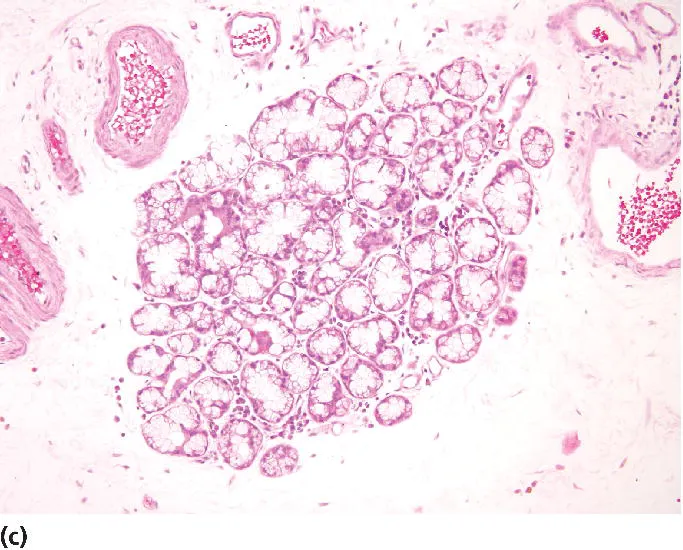

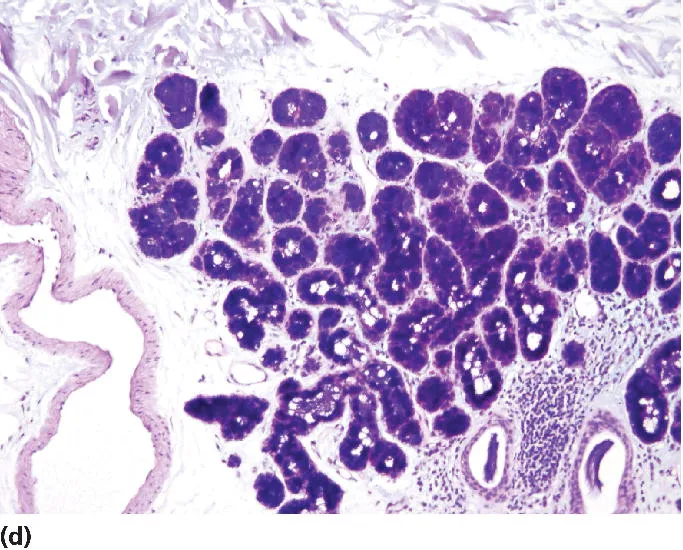

Figure 1.1 Normal histology of the esophagus. (a) Low-power image (H&E stain) of normal esophagus illustrating the characteristic layers of the wall – mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia/serosa. A submucosal gland can be seen at the right side of the image. (b) Medium-power image (H&E stain) of the esophageal mucosa, with stratified squamous epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae. Note the rich vascularity in the lamina propria. (c) High-power image (H&E stain) of an esophageal submucosal gland. (d) High-power image (PAS-AB stain) of an esophageal submucosal gland with characteristic dark blue color.

Beneath the esophageal epithelium is the lamina propria, which contains numerous small capillary-sized blood vessels and lymphatics as well as elastic fibers. The esophageal lamina propria has very few lymphocytes and essentially no eosinophils or plasma cells. The lymphovascular network of the lamina propria facilitates spread of invading cancers, as do similar networks in the stomach and small intestine (but not the colon).

The muscularis mucosae of the esophagus is a slender layer that rapidly thickens in response to injury; resultant reduplication of this layer may make cancer staging difficult. Normally, the smooth muscle fibers of the muscularis mucosae are mostly longitudinal in orientation. There is no skeletal muscle in the esophageal muscularis mucosae (in contrast to the esophageal muscularis propria which contains skeletal muscle fibers). In the upper esophagus, the muscularis mucosae blends with the fibrous membrane of the hypopharynx, whereas in the lower esophagus, it merges with the muscularis mucosae of the stomach.

The submucosa of the esophagus is composed of loose connective tissue with abundant elastic fibers, a rich lymphovascular network that has well-developed venous plexi, scattered ganglion cells, and nerve fibers of Meissner’s plexus. The esophageal submucosa also contains glands (Figure 1.1c and d). These glands are composed of mucin-producing cells that are deeply alcianophilic on periodic acid–Schiff–Alcian blue (PAS-AB) staining. They may undergo various types of metaplasia in response to injury. Ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium convey mucus secreted by the glands to the luminal surface of the esophagus where it lubricates the passage of food.

The esophageal muscularis propria is composed of striated muscle in the upper esophagus, smooth muscle in the lower esophagus, and a mixture of the two in between. The amounts of smooth and striated muscle are said to become equal about 5 cm below the esophageal–pharyngeal junction. There is a well-developed neural plexus (Auerbach’s plexus) between the inner circular and outer longitudinal muscle layers. The inner circular layer of the lower esophagus, or lower esophageal sphincter (LES), contracts or relaxes in response to gastrin or secretin. There are no specific histologic features that distinguish the LES from the rest of the muscularis propria.

The esophagus has an adventitia, a layer of coarse connective tissue that connects the esophagus to adjoining structures, in particular the mediastinum. The adventitia contains thick nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics.

Stomach

The stomach has four parts, each with different mucosal features: the cardia (most proximal), fundus, body, and antrum (most distal). The cardia and antrum are histologically similar and have the function of protecting the esophagus (cardia) or duodenum (antrum) from the acid and enzymes present in the rest of the organ. The cardia expands, and may even be acquired, as a result of acid injury and other insults in the region of the gastroesophageal junction [1–5]. The stomach receives sympathetic innervation from the celiac plexus and parasympathetic innervation from the vagus nerve.

The luminal surface of the em...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 : Structure and innervation of hollow viscera

- CHAPTER 2 : Gastrointestinal hormonesin the regulation of gut function in health and disease

- CHAPTER 3 : Gastrointestinal motility

- CHAPTER 4 : Gastrointestinal immunology and ecology

- CHAPTER 5 : Gastric physiology

- CHAPTER 6 : Structure and functionof the exocrine pancreas

- CHAPTER 7 : Absorption and secretion of fluid and electrolytes

- CHAPTER 8 : Absorption of nutrients

- CHAPTER 9 : Hepatic structure and function

- CHAPTER 10 : The splanchnic circulation

- CHAPTER 11 : Composition and circulation of the bile

- CHAPTER 12 : Bilirubin metabolism

- Index

- Access the Companion Website

- End User License Agreement