eBook - ePub

Heterogeneous Catalysts for Clean Technology

Spectroscopy, Design, and Monitoring

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Heterogeneous Catalysts for Clean Technology

Spectroscopy, Design, and Monitoring

About this book

Reactive, but not a reactant. Heterogeneous catalysts play an unseen role in many of today's processes and products. With the increasing emphasis on sustainability in both products and processes, this handbook is the first to combine the hot topics of heterogeneous catalysis and clean technology.

It focuses on the development of heterogeneous catalysts for use in clean chemical synthesis, dealing with how modern spectroscopic techniques can aid the design of catalysts for use in liquid phase reactions, their application in industrially important chemistries - including selective oxidation, hydrogenation, solid acid- and base-catalyzed processes - as well as the role of process intensification and use of renewable resources in improving the sustainability of chemical processes.

With its emphasis on applications, this book is of high interest to those working in the industry.

It focuses on the development of heterogeneous catalysts for use in clean chemical synthesis, dealing with how modern spectroscopic techniques can aid the design of catalysts for use in liquid phase reactions, their application in industrially important chemistries - including selective oxidation, hydrogenation, solid acid- and base-catalyzed processes - as well as the role of process intensification and use of renewable resources in improving the sustainability of chemical processes.

With its emphasis on applications, this book is of high interest to those working in the industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Heterogeneous Catalysts for Clean Technology by Karen Wilson, Adam F. Lee, Karen Wilson,Adam F. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Industrial & Technical Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to Clean Technology and Catalysis

1.1 Green Chemistry and Clean Technology

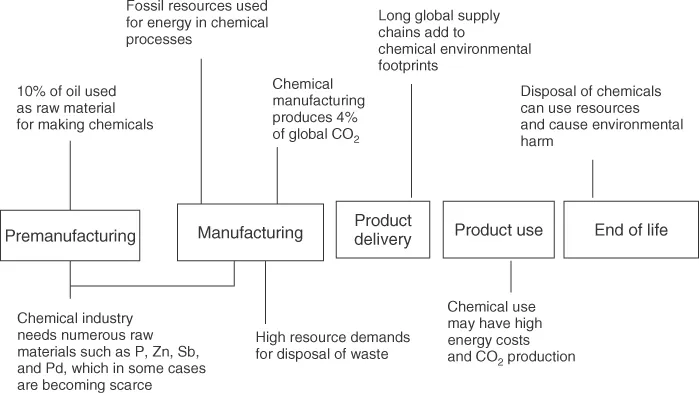

Traditional chemical manufacturing is resource demanding and wasteful, and often involves the use of hazardous substances. Resources are used throughout the production and including the treatment of waste streams and emissions (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Resource demands of traditional chemical manufacturing.

Green chemistry focuses on resource efficiency and on the design of chemical products and processes that are more environmentally benign. If green chemistry is used in a process, it should be made simpler, the inputs and outputs should be safer and more sustainable, the energy consumption should be reduced and costs should be reduced as yields increase, and so separations become simpler and less waste is generated [1]. Green chemistry moves the trend toward new, clean technologies such as flow reactors and microwave reactors, as well as clean synthesis. For instance, lower temperature, shorter reaction time, choice of an alternative route, increased yield, or using fewer washings at workup improve the “cleanness” of a reaction by saving energy and process time and reducing waste [2].

At present, there is more emphasis on the use of renewable feedstocks [3] and on the design of safer products including an increasing trend for recovering resources or “closed-loop manufacturing.” Green chemistry research and application now encompass the use of biomass as a source of organic carbon and the design of new greener products, for example, to replace the existing products that are unacceptable in the light of new legislation (e.g., REACH) or consumer perception.

Green chemistry can be seen as a tool by which sustainable development can be achieved: the application of green chemistry is relevant to social, environmental, and economic aspects.

To achieve sustainable development will require action by the international community, national governments, commercial and noncommercial organizations, and individual action by citizens from a wide variety of disciplines. Acknowledgment of sustainable development has been taken forward into policy by many governments including most world powers notably in Europe [4], China [5], and the United States [6].

1.1.1 Ideals of Green Chemistry

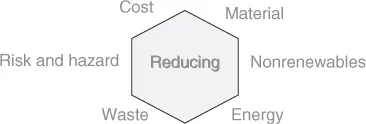

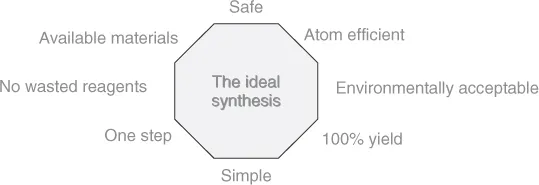

In Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3, the ideals of green chemical synthetic design are shown.

Figure 1.2 Factors for reduction in syntheses.

Figure 1.3 The eight parts of an ideal synthesis.

It is important to note that these green chemistry goals are most effectively dealt with and are easier to apply if they are considered at the design stage rather than retrospectively – green chemistry is not an end-of-pipe solution.

Chemical plants have traditionally concentrated on mechanical safety devices, reducing the probability of accidents. However, mechanical devices are not infallible and safety measures cannot completely prevent the accidents that are happening. The concept of inherently safer design (ISD) was designed with the intention of eliminating rather than preventing the hazards and led to the phrase “What you don't have can't harm you” [7]. ISD means not holding significant inventories of hazardous chemicals or not using them at all.

This approach would have prevented the accident at Bhopal, India in 1984, where many thousands of people were killed or seriously injured. One of the chemicals used in the process at the Union Carbide factory was highly water sensitive, and when a watertight holding tank was breached, the accident occurred, releasing the chemicals into the air, affecting the villages surrounding the factory. The chemical is nonessential and the ISD approach would have been used an alternative, thus eliminating the risk altogether.

Green chemistry research has led to the invention of a number of clever processing technologies to save time and energy or reduce waste production, but these technologies mostly exist in academia and, with very few exceptions, industry has been slow to utilize them. Green chemical technologies include heterogeneous catalysis (well established in some sectors but much less used in fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals, see the subsequent text), use of supercritical fluids (as reaction and extraction media), photochemistry, microwave chemistry, sonochemistry, and synthetic electrochemistry. All these replacements for conventional methods and conductive heating can lead to improved yields, reduced reaction times, and reduced by-product formation. Engineered greener technologies also exist, including a number of replacements for the stirred tank batch reactor, such as continuous stirred tanks, fluidized bed reactors, microchannel reactors, and spinning disc reactors as well as microwave reactors, all of which increase the throughput, while decreasing the energy usage and waste. Unfortunately, despite these many new processes, industry is reluctant to use these hardware solutions because of the often massive financial expenditure involved in purchasing these items and the limited number of chemistries that have been demonstrated with them to date. There is also a reluctance to change well-established (and paid for) chemical plant so that newer, cleaner technologies may well have more success in the developing (e.g., the Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC)) nations, where the chemical industry is growing and new plant is required to meet the increasing expectations of local and increasingly affluent markets.

1.2 Green Chemistry Metrics

It is important to be able to quantify the change when changes are made to chemical processes. This enables us to quantify the benefit from the new technology introduced (if there are benefits). This can aid in in-house communication (to demonstrate the value to the workforce) as well as in external communication. For yield improvements and selectivity increases, simple percentages are suitable, but this simplistic approach may not always be appropriate. For example, if a toxic reagent is replaced by a less toxic one, the benefit may not be captured by conventional methods of measuring reaction efficiency. Equally, these do not capture the mass efficiency of the process – a high-yielding process may consume large amounts of auxiliaries such as solvents and reagents, as well as those used in product separation and purification. Ideally, we also need to find a way to include energy and water, both of them have been commonly used in a rather cavalier way but they are now subject to considerable interest that they can vary depending on the location of the manufacturing site.

Numerous metrics have been formulated over time and their suitability discussed at great length [8–12]. The problem observed is that the more accurate and universally applicable the metric devised, the more complex and unemployable it becomes. A good metric must be clearly defined, simple, measurable, objective rather than subjective, and must ultimately drive the desired behavior. Some of the most popular metrics are

E factor (which effectively measures the amount of product compared to the amount of waste – the larger the E factor is, the less product-specific is the process; the fine chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturing sectors tend to have the highest E factors) [13];

effective mass yield (the percentage of the mass of the desired product relative to the mass of all nonbenign materials used in its synthesis – this includes an attempt to recognize that “not all chemicals are equal” – important and very real but very difficult to quantify);

atom efficiency/economy (measures the efficiency in terms of all the atoms involved and is measured as the molecular weight of the desired product divided by the molecular weight of all of the reagents; this is especially valuable in the design “paper chemistry” stage when low atom efficiency reactions can be easily spotted and discarded);

reaction mass efficiency (essentially the inverse of E factor).

Of course, the ultimate metric is life cycle assessment (LCA); however, this is a demanding exercise that requires a lot of input data, making it inappropriate for most decisions made in a process environment. However, some companies do include LCA impacts such as greenhouse gas production in their in-house assessment, for example, to rank solvents in terms of their greenness. It is also essential that we adopt a “life cycle thinking” approach to decision making so that we do not make matters worse when greening one stage in a manufacturing process without appreciating the effects of that change on the full process including further up and down the supply chain.

1.3 Alternative Solvents

Most chemical processes involve solvents – in the reactions and in the workups as well as in the cleaning operations [14, 15]. The environmental impact of a chemical process cannot be properly evaluated without considering the solvent(s). For some time there has been a drive toward replacing or at least reducing the use of traditional volatile organic solvents such as dichloromethane, tetrahydrofuran, and N-methylpyrollidone – commonly used solvents in, for example, catalytic processes.

Ionic liquids, fluorous biphasic systems, and supercritical fluids have all been studied as alternatives to conventional organic solvents. However, because of their nature, some of these novel systems require additional hardware for utilization. For example, some suppliers have designed advanced mixing systems to enable polyphasic systems to be intimately mixed at the laboratory scale. There has also been considerable rethinking of the green credentials of some of these alternative solvents in recent years and many ionic liquids are no longer considered suitable because of their complex syntheses, toxicity, or other unacceptable properties, or difficulty in separation and purification. Fluorous solvents (which are based on heavily fluorinated usually aliphatic compounds) are not considered to be environmentally compatible (as they persist in the environment).

Supercritical solvents are difficult to manipulate because of the high pressures and temperatures often employed. In the case of supercritical water, equipment had to be designed, which could contain the highly corrosive liquid. Vessels for creating supercritical solvents such as supercritical CO2 (scCO2) are now available and are capable of fine adjustments in temperature and pressure to affect the solvents' properties. Very high pressure and temperatures are not required to produce scCO2 and it is becoming an increasingly popular reaction medium as its properties are controllable by varying the temperature and pressure or by the use of a cosolvent [16]. The main environmental benefit of scCO2 lies in the workup, as the product mixture is obtained free from solvent by simply returning to atmospheric conditions. Additionally, carbon dioxide is nontoxic, nonflammable, recyclable, and a by-product of other processes. However, there are energy and safety concerns associated with the elevated temperatures and pressures employed and in particular, there are high capex costs to install a plant. These must be balanced against the benefits of its use.

scCO2 can be a good medium for catalysis, although its low polarity means that either catalysts are heterogeneous or they have to be modified to enable them to dissolve (e.g., by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Introduction to Clean Technology and Catalysis

- Chapter 2: Mechanistic Studies of Alcohol Selective Oxidation

- Chapter 3: Reaction Monitoring in Multiphase Systems: Application of Coupled In Situ Spectroscopic Techniques in Organic Synthesis

- Chapter 4: In Situ Studies on Photocatalytic Materials, Surface Intermediates, and Reaction Mechanisms

- Chapter 5: Enantioselective Heterogeneous Catalysis

- Chapter 6: Mechanistic Studies of Solid Acids and Base-Catalyzed Clean Technologies

- Chapter 7: Site-Isolated Heterogeneous Catalysts

- Chapter 8: Designing Porous Inorganic Architectures

- Chapter 9: Tailored Nanoparticles for Clean Technology – Achieving Size and Shape Control

- Chapter 10: Application of Metal–Organic Frameworks in Fine Chemical Synthesis

- Chapter 11: Process Intensification for Clean Catalytic Technology

- Chapter 12: Recent Trends in Operando and In Situ Characterization: Techniques for Rational Design of Catalysts

- Chapter 13: Application of NMR in Online Monitoring of Catalyst Performance

- Chapter 14: Ambient-Pressure X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

- Index