![]()

Chapter 1

The State of Wellbeing Science

Concepts, Measures, Interventions, and Policies

Felicia A. Huppert

University of Cambridge, U.K. and Centre for Positive Psychology and Education University of Western Sydney, Australia

What is Wellbeing?

Wellbeing is a fundamental human goal—we all have a desire for our life to go well. The experience of life going well involves both feeling good and functioning well. Feeling good all the time would not be conducive to wellbeing, as it would devalue the role of negative or painful emotions, which play an important part in our lives when experienced in the appropriate context, such as sadness following misfortune, and distress or even anger following injustice. Some scholars define wellbeing in terms of positive emotions alone (e.g., Layard, 2005, 2011) or the balance of positive to negative emotions (e.g., Kahneman & Krueger, 2006). However, emotional experiences or “hedonic” wellbeing are only part of wellbeing, since emotions are by their nature transient, whereas wellbeing refers to a more sustainable experience. Sustainable wellbeing includes the experience of functioning well, for instance, having a sense of engagement and competence, being resilient in the face of setbacks, having good relationships with others, and a sense of belonging and contributing to a community. The functioning component of wellbeing is similar to Aristotle's notion of eudaimonic wellbeing, and a number of scholars have equated psychological wellbeing with eudaimonic wellbeing (e.g., Ryan, Huta, & Deci, 2008; Ryff, 1989; Waterman, 1993). However, the more general sense of wellbeing described here combines both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects. This combined position has been taken by a number of authors (Huppert, 2009; Keyes, 2002b; Marks & Shah, 2005; Seligman, 2002, 2011).

Some scholars use a very broad definition of happiness that is roughly synonymous with the combined hedonic/eudaimonic view of wellbeing described above. Sometimes this is termed “authentic happiness” (e.g., Seligman, 2002) or “real happiness” (e.g., Salzberg, 2010). The notion of happiness enshrined in Bhutan's Gross National Happiness (GNH) is another example of a very broad use of the term. In the words of Jigmi Thinley, the prime minister of Bhutan: “This ‘happiness’ has nothing to do with the common use of this word to describe an ephemeral, passing mood–happy today or unhappy tomorrow due to some temporary external condition like praise or blame, gain or loss. Rather, it refers to . . . deep, abiding happiness” (United Nations, 2012, p. 89).

Wellbeing can be used to describe an objective state as well as a subjective experience. Objective wellbeing refers to wellbeing at the societal level: the objective facts of people's lives; this contrasts with subjective wellbeing, which concerns how people actually experience their lives. As an objective state, wellbeing relates to the quality of outcomes for which a government or organization traditionally regards itself to be responsible; for example, education, health, employment, housing, security, and the environment. In this context, the term wellbeing is often used synonymously with welfare, the latter term emphasizing what governments do to improve objective wellbeing, as opposed to simply evaluating wellbeing. Used in its subjective sense, wellbeing refers to the way citizens experience their lives, which may bear a strong or only a weak relationship to the objective facts of people's lives. This chapter, and indeed this volume, is focused primarily on wellbeing in its subjective sense. As with objective wellbeing, we can examine its components and current state, and the variety of ways in which efforts have been made, or are being made, to improve it.

What is the Relationship Between Wellbeing and Illbeing?

Wellbeing versus the Absence of Illbeing

A senior civil servant in the United Kingdom recently made the encouraging comment that wellbeing is the core aim of all government departments. He went on to explain that since no department has the intention of making life worse for citizens, wellbeing must therefore be their goal. This comment reflects a classic misunderstanding of the relationship between wellbeing and illbeing.

Wellbeing is more than the absence of illbeing, just as health is more than the absence of disease (World Health Organization, 1946). Yet it is remarkable how resistant large sectors of the academic, practitioner, and policy communities are to recognizing the importance of positive wellbeing or of positive health. Many, if not most of the studies that purport to improve health or wellbeing in fact focus on symptom reduction, and their outcome measures usually do not even include assessment of positive feeling or positive functioning. Surprisingly, this is even true of the numerous trials using the Penn Resiliency Program undertaken in various parts of the world to increase social and emotional wellbeing in schoolchildren (Challen, Noden, West, & Machin, 2011; Gillham et al., 2007). The primary outcome measure has been reduction in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and conduct disorders. In the same way, school-based interventions to prevent bullying rarely go on to examine improvements in subjective wellbeing, interpersonal relationships or pro-social behavior. Likewise, work-based interventions too often assume that wellbeing will result from programs designed to reduce stress, but rarely do they evaluate increases in positive emotions, vitality, perceived competence, and the like. However, as contributions to this volume indicate, the situation is beginning to change, and increases in positive wellbeing outcomes are beginning to be measured in addition to decreases in negative wellbeing outcomes.

Unfortunately, resistance to prioritizing positive outcomes remains high in the field of health, including mental health. In the 1930s, a working group involved in planning a national health system for the United Kingdom wrote:

Health must come first: the mere state of not being ill must be recognised as an unacceptable substitute, too often tolerated or even regarded as normal. We must, moreover, face the fact that while immense study has been lavished on disease, no-one has intensively studied and analysed health, and our ignorance of the subject is now so deep that we can hardly claim scientifically to know what health is.

Political and Economic Planning (1937), p. 395

Sadly, within the medical profession the situation has hardly changed over the intervening 80 years, although some recent attempts are being made to conceptualize and measure positive physical health (e.g., Seeman, 1989; Seligman, 2008). One manifestation of this is the refocusing which has taken place within the American Heart Association, which now emphasizes cardiovascular vitality rather than cardiovascular disease. Within the mental health profession, an encouraging sign comes from the collaborative recovery model, where it is recognized that patients want to move beyond the absence of symptoms, towards feeling good and being fully functional (Oades et al., 2005).

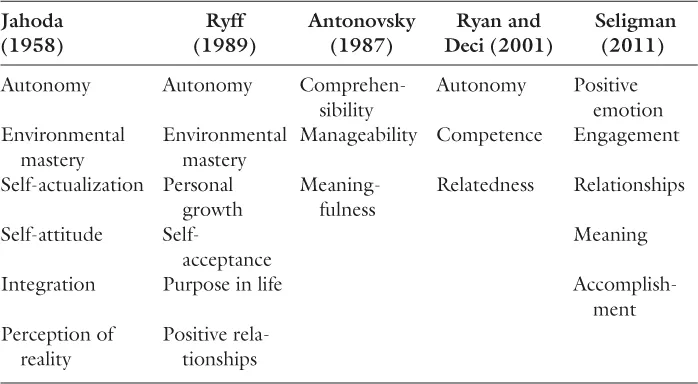

Wellbeing as Positive Mental Health

The real developments in positive mental health, however, have come from non-clinicians, including psychologists, social scientists, and public health researchers, Jahoda (1958) is generally regarded as the first person to have promoted the idea of positive mental health, which she defined in terms of six elements of positive functioning: “attitudes of an individual towards his own self,” “self-actualization,” “integration,” “autonomy,” “perception of reality,” and “environmental mastery” (Table 1.1). In the 1980s, Ryff (1989) proposed six dimensions of positive mental health or “psychological wellbeing” that bear some resemblance to Jahoda's six elements of positive functioning: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relationships, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Antonovsky (1987) coined the term “salutogenesis” to promote an interest in the development of health rather than of disease. Central to his concept of health is a “sense of coherence,” whereby life is seen as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful. All three of these theorists view mental health and mental illness as lying along a continuum, with mental illhealth at one end and mental health at the other, although each has a different list of what they regard as the key components of mental health.

Table 1.1 Components of Positive Mental Health or Psychological Wellbeing.

Other wellbeing theorists do not explicitly refer to a mental illness/health continuum but can nevertheless be regarded as contributing to the body of theories about what constitutes positive mental health. Seligman, who initially regarded wellbeing (“authentic happiness”) as the combination of pleasure, engagement, and meaning (Seligman, 2002), has added two components in his more recent book (Seligman, 2011). These are relationships and accomplishment, which creates the acronym PERMA: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment. For Ryan and Deci (2001), wellbeing arises from the fulfilment of what they describe as the basic psychological needs, and which they identify as autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

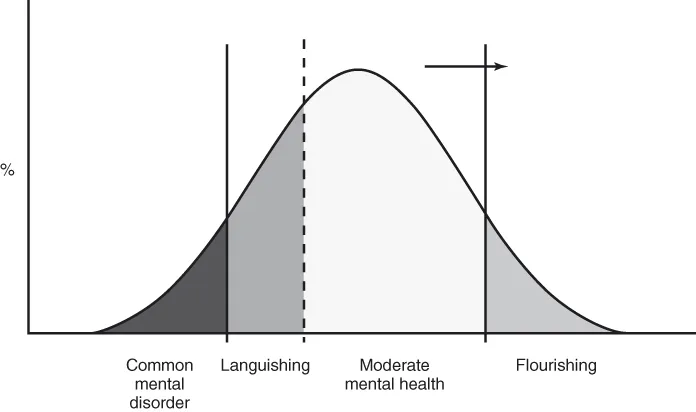

Although there is substantial overlap between these major theoretical approaches to psychological wellbeing or positive mental health, each scholar has their own preferred list of components. A recent paper by Huppert and So (2013) endeavored to derive a list of the components of psychological wellbeing in a more objective manner. They began by proposing a single, underlying mental health spectrum, with mental illbeing at one end and mental wellbeing at the opposite end. This meant that they conceived wellbeing not as the absence of illbeing, but as its opposite (Figure 1.1). To establish the components that comprise wellbeing, they examined the internationally agreed criteria for the common mental disorders (as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV, and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-10) and for each symptom listed the opposite characteristic. This resulted in a list of 10 features which represent positive mental health or “flourishing”: competence, emotional stability, engagement, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationships, resilience, self-esteem, and vitality. And just as symptoms of mental illness are combined in specific ways to provide an operational definition of each of the common mental disorders, they proposed that positive features could be combined in a specific way to provide an operational definition of flourishing.

Having an operational definition of flourishing makes it possible to examine the prevalence of flourishing within or between groups and the factors associated with flourishing.

One Mental Health Continuum or Two?

There is an alternative school of thought which proposes that mental wellbeing and illbeing are not at opposite ends of a continuum, but rather form two different continua. According to this view, it is possible to have both a serious mental illness, and be flourishing at the same time. The strongest proponent of the two-continua model is Keyes (2002b); one continuum goes from severe mental disorder to no mental disorder, while the other goes from low wellbeing (“languishing”) to high wellbeing (“flourishing”). This is a reasonable position to take in the case of certain chronic mental disorders, such as schizophrenia or personality disorder, in which there are undoubtedly times when the person may be feeling and functioning well, despite their clinical diagnosis. But it is argued by Huppert and So (2013) that this model is less convincing in relation to the common mental disorders, such as major depression and anxiety. Such disorders are common both in the sense that they are very prevalent in the population, and in the sense that virtually any member of the population may be diagnosed with one of these disorders at some point in their life. It is difficult to conceive how someone with a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder could be regarded as flourishing at the same time. Certainly in the course of recovery, when the person no longer meets diagnostic criteria, and is feeling and functioning better, they may move towards flourishing. Indeed it is encouraging that the recovery model now recognizes that for patients who have had a mental disorder, it is not sufficient to be relieved of their symptoms; rather, they want to be able to feel good and function well.

The fact that symptoms of mental disorder can coexist with some features of flourishing is not in doubt; it is the interpretation of this coexistence which requires examination. For example, in a representative population sample of over 6,000 U.K. adults, Huppert and Whittington (2003) created scales of both positive and negative wellbeing from the General Health Questionniare (GHQ-30) (Goldberg, 1972; Goldberg & Williams, 1988) and reported that there was some degree of independence between these measures. While the majority of people (65%) who had high scores on one of the scales (either high negative or high positive) had low scores on the other scale, 35% either had high scores on both positive and negative wellbeing measures, or low scores on both. There are at least two explanations ...