eBook - ePub

Violence Risk - Assessment and Management

Advances Through Structured Professional Judgement and Sequential Redirections

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Violence Risk - Assessment and Management

Advances Through Structured Professional Judgement and Sequential Redirections

About this book

This expanded and updated new edition reflects the growing importance of the structured professional judgement approach to violence risk assessment and management. It offers comprehensive guidance on decision-making in cases where future violence is a potential issue.

- Includes discussion of interventions based on newly developed instruments

- Covers policy standards developed since the publication of the first edition

- Interdisciplinary perspective facilitates collaboration between professionals

- Includes contributions from P.Randolf Kropp, R. Karl Hanson, Mary-Lou Martin, Alec Buchanan and John Monahan

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Violence Risk - Assessment and Management by Christopher D. Webster,Quazi Haque,Stephen J. Hucker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Forensic Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Decision Points

…practitioners should approach the task of risk assessment with transparency, circumspection and humbleness.

(Cooke & Michie, 2013, p. 3)

Laws

Perhaps the most important aspect of any violence risk management activity relates to the pertinent law, be it local, national, or international. Statutes and how they are interpreted by case law determine how the violence risk assessment should proceed and which interventions are permissible.

Although this text is not written to promote understanding of the legal approach to mentally disordered offenders in a specific country, it is nonetheless instructive to outline this particular path. There are similarities among legal systems in Canada, most states in the United States, and many western European countries (see Melton et al., 1997).

Criminal law and mental health law will vary across countries and may change with time. Legal and mental health systems intersect at frequent points, often with different values and objectives. Mental health practitioners are focused on welfare of the individual client and the reduction of the patient’s risk of harming themselves or others. The legal system, comprising the civil, criminal, and other courts and tribunals, is concerned with the interests of society as a whole and the administration of justice. Justice is a multifaceted concept that is based on principles of directing punishment and retribution, deterrence, seeking reparation for victims, and rehabilitating offenders while maintaining public safety.

Civil mental health legislation will usually provide criteria for compulsory detention or treatment. The criteria often relate to the presence of a mental disorder and, in broad terms, risk (whether to self or others) or impaired decision-making capacity or competence, irrespective of whether any criminal law has been broken. Despite variations in definitions between jurisdictions, proof of risk of bodily harm is a common threshold for justifying commitment on grounds of risk of violence. Commentators seem to agree that three key variables influence whether a particular risk is significant, that is, (i) severity, (ii) imminence, and (iii) likelihood (e.g., Litwack, 2001; Melton et al., 1997). “A workable standard would not be any kind of violence at any time in the future. Rather, a proper measure would be sufficiently serious violence occurring sufficiently soon in the future that, had it been foreseen, would have justified continued commitment” (Litwack, 2001, p. 432). Although there are international differences in how judicial or quasi-judicial bodies review the process of detention, developed countries have tended to establish their own laws over time. The absence of such mechanisms would violate any established human rights legislation.

Criminal mental health legislation comes into play to allow compulsory treatment or detention after a mentally disordered offender has been convicted. There are earlier stages at which an individual with mental health difficulties may be diverted for assessment and treatment, but the main point is that in many European countries, United States, and Canada, the criminal law provides a range of sentences or remedies to allow risk management through treatment. Historically, the extent of such interventions has been mainly determined by the degree of emphasis placed on risk management by any pertinent criminal justice policy.

Interfaces

Law and psychiatry tend to regard each other with circumspection. Each has its own language, purposes, and professional rituals. Clinicians attempt to convey the meaning of complex and sometimes subtle influences of mental illness in settings where legal constructs and language are often binary in nature. Courts seek to find truth while psychiatry looks for meaning within information. Because scientific “certainty” changes almost every day, the law tends to incorporate the fruits of research with caution. Some law is quite vague in its wording about “dangerousness” and violence risk, some is remarkably detailed, some of it is more or less unaffected by medical or social research findings and observations, and some of it has incorporated recent scientific thinking and language. What is important to note, though, is that practitioners alike are obliged to work within the ambit of the applicable law. It is the necessary starting point at each decision point.

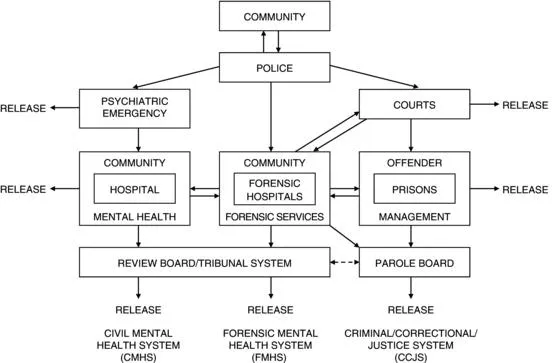

The title of this chapter is influenced by Saleem Shah’s article in 1978 which presciently described the scientific and ethical issues that may arise when making violence risk evaluations at key decision points. These decision points can be found at the various interfaces that arise between communities: the Civil Mental Health System (CMHS), the Forensic Mental Health System (FMHS), and the Criminal/Correctional/Justice System (CCJS). Figure 1.1 describes a general layout of these systems.

Figure 1.1 Schematic diagram portraying possible linkages between CMHS, FMHS and CCJS.

There are certain notable features about the relationship between these three main systems.

- Individuals with mental health difficulties often drift between systems, and it can be very difficult to monitor them for the purposes of treatment or maintaining supervision by health or criminal justice agencies.

- Most complaints, disruptions, or criminal activities are dealt with by police officers. When they attend an incident, they have to make a decision whether the individual is routed to the criminal justice or mental health system. Of course, in many instances, they cannot exercise much discretion. If the incident is highly serious, one involving say substantial physical injury, they have no alternative but to lay charges. In the majority of cases, they have to make what seems to be the best decision at the time. If there is no specific specialist support, the decision whether to be diverted to a mental health facility can be complex if the history of the individual is unknown and their presentation is complicated by factors such as intoxication or communication difficulties.

- The vast majority of acts of violence carried out by psychiatric patients occur when in contact with general, not forensic services (Appelby et al., 2006). Patients with schizophrenia who commit crime and end up in the FHMS are more likely than not to have been in contact with CMHS often before the index offense (Hodgins, 2009; Hodgins & Müller-Isberner, 2004).

- The prison population is rising in many countries with concerning high rates of severe mental disorder within these settings (Fazel & Seewald, 2012). Vulnerable groups such as young people, the elderly, and those with intellectual disability have particular difficulty in gaining access to specialized mental health services. Strategies to provide treatment for these groups of individuals through diversion to CMHS or FMHS, or in combination with bolstering prison healthcare services, can fall short often due to the challenges entailed in coordinating different organizations, especially if economic pressures are prevalent.1,2

- The mental health system does not operate in isolation from the criminal justice system, and vice versa. Penrose (1939) long ago observed that as the population in one rises, the other tends to drop. Similar trends may occur between civil and forensic mental health systems. Many countries have developed community alternatives to hospital admission. For example, Keown et al. (2011) suggest that in England such service reorganizations are associated with an increased relative rate of involuntary admissions to hospital for persons with mental illness.

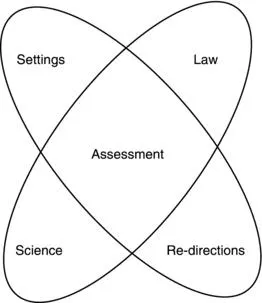

Figure 1.2 Risk appraisal practices viewed as being in need of constant reappraisal and refinement.

These observations also serve to emphasize the point made in Figure 1.2 that the nature of violence risk assessments can shift gradually or even dramatically with the introduction of new law, new scientific findings, and new advances in interventions or treatments (redirections) and through experience gained in other jurisdictions or systems. Such changes can also greatly affect clinical, administrative, and research practices. Indeed, clinicians who choose to work in this area have constantly to be evaluating their limits, those imposed by law, by the ability to keep up with changes in professional standards, and by an ever-increasing accumulation of scientific evidence.

Since Shah’s article, there have been further increases in the number of decision points across these systems whereby an individual’s risk of harm to others is considered. The juvenile criminal justice system, for example, has developed in many countries to provide the opportunity for diversion and rehabilitation on the grounds of welfare. Some settings are in the margins of the systems described previously (e.g., immigration centers, social care settings) where the criterion for intervention on the grounds for risk posed to others may be vague. This dilemma can be compounded if there is doubt about the extent of one’s own role at such interfaces. In recent years, mental health services in the United Kingdom and some US states have extended in scope to include broader public protection functions. Those societies in which such systems operate place increased demands to manage the risks posed by mentally disordered offenders regardless of whether the mental disorder is amenable to treatment. Redirecting the potential manifestation of violence has thus become the treatment target (see Maden, 2007).

As suggested earlier, particular ethical dilemmas commonly arise when mental health legislation is widened to allow detention for treatment for conditions where welfare-based approaches can be difficult to demonstrate at the very least. A prominent example of this is the now reconfigured English “Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD)” program which caused many psychiatrists and lawyers to express concern about a public protection agenda being dressed up in the name of healthcare (see Duggan, 2011). Within this landscape, mental health professionals have already found themselves increasingly pushed to give opinions on risk-based sentencing.3

Professional Ethics and Standards

The inherent difficulty of predicting future behavior while working across a range of different decision points can appear daunting to even the most experienced practitioners in the field. Each system and interface has its own set of priorities, policies, and language. How does one practice ethically and effectively in such conditions? A basic standard would be to recognize that defensibility rather than certainty is a goal of risk assessment practice. A defensible risk assessment is one which is judged to be as accurate as possible and which would stand up to scrutiny if the handling of the case were to be investigated (Kemshall, 1998, p. 113). This principle is, of course, different to defensive risk management. The latter being an approach in which a fear of what may happen interferes with a clinician’s or team’s ability to taking an evidence-based approach to risk taking. A defensible approach can better conceptualized as those evaluations when all reasonable steps have been taken, reliable assessment methods have been used, information is collected and thoroughly evaluated, decisions are recorded, staff work within agency policy and procedures, and the practitioner or staff communicate with others and seek information they do not have (Kemshall, 2003).4

Personal professional guidelines are strengthened if there is an overarching set of standards agreed by the relevant professional bodies and enshrined in policy. The proliferation of evidence-based practice in medicine has led to many best practice guidelines being issued. Many fail at implementation. It is therefore notable that expert groups in the Risk Management Authority (RMA) of Scotland (2005), the Department of Health for England and Wales (DoH, 2007), and the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP, 2008) all decided that there was sufficient evidence to develop best practice guidelines for managing clinical risk. The recommendations from these national bodies share similar principles (see Box 1.1) and can be applied by practitioners and services at many of the decision points observed earlier.5,6

Box 1.1 Best practices in managing risks (themes loosely adapted from guidelines proposed by the DoH (2007), RCP (2...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Tribute

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Boxes

- About the Authors

- Foreword

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Decision Points

- 2 Points of View

- 3 Predictions and Errors

- 4 Developmental Trajectories

- 5 Symptomologies

- 6 Personality Disorders

- 7 Substance Abuse

- 8 Factors

- 9 SPJ Guides

- 10 Competitions

- 11 Planning

- 12 Transitions

- 13 Sequential Redirections

- 14 Implementations

- 15 Teaching and Researching SPJ Guides

- 16 Spousal Assaulters

- 17 Sex Offenders

- 18 Teams

- 19 Communications

- 20 Getting It Wrong, Getting It Right (Mostly)

- Questions

- Afterword

- References

- Index