![]()

1

HISTORY OF BIOMIMETIC, BIOACTIVE, AND BIORESPONSIVE BIOMATERIALS

Matteo Santin and Gary Phillips

1.1 THE FIRST GENERATION OF BIOMATERIALS: THE SEARCH FOR “THE BIOINERT”

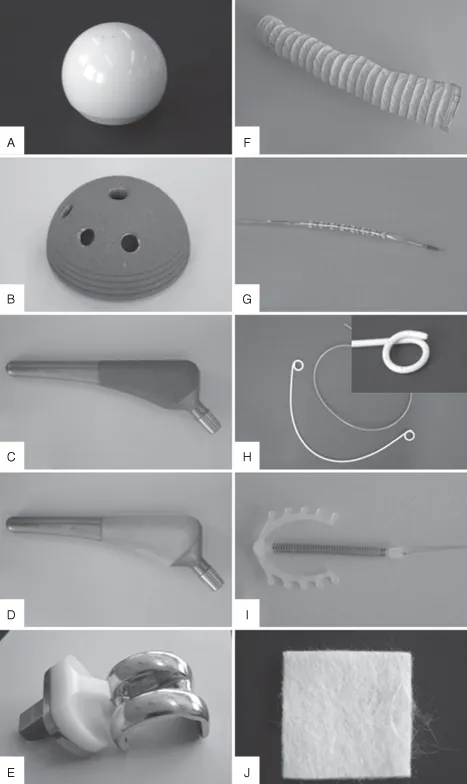

Since it was first perceived that artificial and natural materials could be used to replace damaged parts of the human body, an “off-the-shelf” materials selection approach has been followed. These materials, now referred to as “first-generation” biomaterials, tended to be “borrowed” from other disciplines rather than being specifically designed for biomedical applications, and were selected on the basis of three main criteria: (1) their ability to mimic the mechanical performances of the tissue to be replaced, (2) their lack of toxicity, and (3) their inertness toward the body’s host response [Hench & Polack 2002].

Following this approach, pioneers developed a relatively large range of implants and devices, using a number of synthetic and natural materials including polymers, metals, and ceramics, based on occasional earlier observations and innovative approaches by clinicians. Indeed, many of these devices are still in use today (Figure 1.1A–J). A typical example of this often serendipitous development process was the use of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) to manufacture intraocular and contact lenses. This material (Table 1.1) was selected following observations made by the clinician Sir Harold Ridley that fragments of the PMMA cockpit that had penetrated into the eyes of World War II pilots induced a very low immune response (see Section 1.3.1) [Williams 2001].

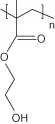

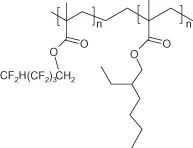

TABLE 1.1. Chemical Structure of Typical Polymeric Biomaterials

|

| Polystyrene | |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) | |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) | |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | |

| Chronoflex 80A poly(urethane) | -(-PHECD-DesmW-BD-)-n |

| Hydrothane poly(urethane) | Polyethylene glycol polyurethane |

| PFPM/PEHA75/25 | |

| Poly(octofluoropentyl methacrylate/ethylhexyl methacrylate) |

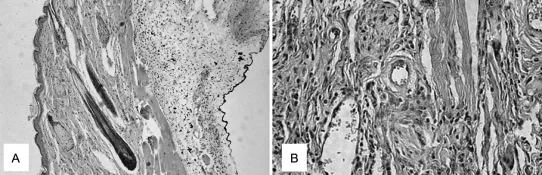

Also against the backdrop of the Second World War, a young Dutch physician named Willem Kolff pioneered the development of renal replacement therapies by taking advantage of a cellophane membrane used as sausage skin to allow the dialysis of blood from his uremic patients against a bath of cleansing fluid [Kolff 1993]. Later, in the early 1960s, John Charnley, learning about the progress materials science had made in obtaining mechanically resistant metals and plastics, designed the first hip joint prosthesis able to perform satisfactorily in the human body [Charnley 1961]. These are typical examples of how early implant materials were selected; however, it was soon recognized that the performance of these materials was often limited by the host response toward the implant, which often resulted in inflammation, the formation of a fibrotic capsules around the implant, and poor integration with the surrounding tissue (Figure 1.2A,B) [Anderson 2001].

The poor acceptance and performance of early biomaterials indicated that their interaction with body tissues was a complex problem that required the development of more sophisticated products. As a result, it was realized that inertness was not a guarantee of biocompatibility. Indeed, in 1986, the Consensus Conference of the European Society for Biomaterials put in place widely accepted definitions of both biomaterials and biocompatibility, which took into account the interaction between an implanted material and biological systems. According to these definitions, a biomaterial was “a nonviable material used in a medical device intended to interact with biological systems,” whereas biocompatibility was defined as “the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application” [Williams 1987]. Perhaps for the first time, materials scientists and clinicians had an agreement on what their materials should achieve. However, as you will see later in this chapter and throughout this book, the ever-expanding fields of biomaterials science and tissue engineering call for newer and more specific definitions.

1.1.1 Bioinert: Myth, Reality, or Utopia?

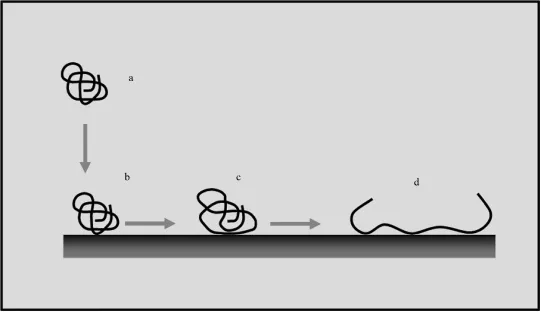

In the 1980s, the formation of a fibrotic capsule “walling off” many biomedical implants from the surrounding tissue triggered biophysical and immunological studies that identified the molecular, biochemical, and cellular bases of the host response that caused the formation of this interposed and pathological tissue [Williams 1987; Anderson 1988]. In particular, many studies highlighted that this host response could not be avoided due to the immediate deposition of proteins onto the material surfaces and their change of conformation [Norde 1986]. The material surface-induced conformational changes transformed the host proteins into foreign molecules, antigens, which were capable of eliciting a foreign body response by the host (Figure 1.3).

Biomaterial surfaces contacted by blood, saliva, urine, cerebrospinal and peritoneal fluids, or tears cannot avoid interactions with proteins and other molecules that are naturally contained in the overlying body fluid [Santin et al. 1997]. As a consequence, the implant surface is rapidly covered by a biofilm that masks the material surface and dictates the host response. It is clear, therefore, that as a result of these processes, no biomaterial can be considered to be totally inert. However, although they are subjected to a continuous turnover, it is a fact that proteins (and more broadly, all tissue macromolecules) retain their native conformation during the different phases of tissue formation and remodeling. Hence, for the past two decades the scientific community has striven for the development and synthesis of a new generation of biomaterials that are able to control protein adsorption processes and/or tissue regeneration around the implant.

1.2 THE SECOND GENERATION OF BIOMATERIALS: BIOMIMETIC, BIORESPONSIVE, BIOACTIVE

In conjunction with the findings regarding the biochemical and cellular bases of host response toward implants, material scientists began their search for biomimetic, bioresponsive, and bioactive materials capable of controlling interactions with the surrounding biological environment and that could participate in tissue regeneration processes.

The move toward the synthesis and engineering of this type of biomaterial was initiated by the discovery of ceramic biomaterials that were proven to favor the integration of bony tissue in dental and orthopedic applications [Clarke et al. 1990], as well as by the use of synthetic or natural polymers [Raghunath et al. 1980; Giusti et al. 1995]. Second-generation metals also emerged that were able to improve the integration with the surrounding tissue.

1.2.1 Hydroxyapatite (HA) and Bioglass®: Cell Adhesion and Stimulation

The ability of HA, and Bioglass to integrate with the surrounding bone in orthopedic and dental applications strictly depends on the physicochemical properties of these two types of ceramics, which will be described in Chapter 7. Here, it has to be mentioned that since their early discovery and use in surgery, the good integration of these biomaterials with bone, the osteointegration, depends on mechanisms of different nature that have triggered new concepts/definitions and new technological targets among scientists.

Although HA osteointegration can intuitively be attributed to their ability to mimic the bone mineral phase (see Chapter 3), the mechanisms underlying Bioglass-induced bone formation are not as clearly identifiable. It is known that HA favors the deposition of new bone on its surface by supporting osteoblast adhesion and by promoting the chemical bonding with the bone mineral phase [Takeshita et al. 1997]. Furthermore, the ability of HA to induce bone formation when implanted intramuscularly in animals, allegedly via the differentiation of progenitor cells, clearly shows their osteoinductive potential; indeed, osteoinductivity is defined as the ability of a biomaterial to form ectopic bone. Conversely, Bioglass osteoinductivity seems to be intrinsic to its degradation process whereby (1) growth factors remain trapped within the gel phase formed during the degradation of the material and, consequently, released to the cells upon complete material dissolution; (2) structural proteins of the extracellular matrix (ECM) such as fibronectin form strong bonds with particles of the degrading material; and (3) silicon ions stimulate osteoblast (and allegedly progenitor cell) differentiation and, subsequently, the production of new bone [Xynos et al. 2000]. Regardless of the type of ceramic used, it is now widely recognized that the topographical features of these types of biomaterials are also fundamental to their bioactivity. For example, the absence of porosity or porosity of different sizes may lead to no osteointegration or to only poor bone formation [Hing et al. 2004].

1.2.2 Collagen, Fibrin Glue, and Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels: Presenting the ECM

The use of collagen, fibrin, and hyaluronan, which are all natural components of the ECM, was born from scientists’ intuition that tissue cells recognize these biopolymers as natural substrates to form new tissue.

Fundamental to the application of these biological materials was an appreciation of their physicochemical and biological properties. Collagen is the most ubiquitous structural protein in the human body and the principal constituent of ECM in connective tissues [Rivier & Sadoc 2006]. It consists of a tightly packed structure composed of three polypeptide chains that wind together to form a triple helix [Rivier & Sadoc 2006]....