![]()

Part I

Product considerations: medicinal formulations

All medicines and therapeutics formulated as ‘emulsions’ must typically and characteristically contain consistent amounts and specified polymorphic forms of the relevant drug (Mahato, 2007). Depending on the route of administration, some intervention may be required in order to pasteurise or sterilise the sample and thus reduce the risk of microbial growth and pathogenicity or the production of toxins. Unfortunately, most pharmaceutical dispersions, including emulsions, are thermodynamically unstable (metastable) and undergo significant change upon heating or irradiation as a consequence of changes in bulk and interfacial rheology (Sarker et al., 1999).

A patient receiving a cytotoxic drug intravenously in the form of a fine emulsion dispersion requires as a minimum that the product be suitably pure (P), suitably consistent (C) between batches and free from injurious elements, for example pathogenic microorganisms, spores and toxins, and thus of appropriate quality (Q). Acceptable PCQ is essential in any high-quality medicine (Sarker, 2008). Topical medicines (Sarker, 2006b) do not necessarily require the same degree of sterility (unless applied to broken skin), but it is worth striving for, as poor quality (Di Mattia et al., 2010) lessens product shelf life.

Shape, size, polydispersity and surface coverage (Sarker et al., 1999) all impact on the shelf life and efficacy (Sarker, 2005a, 2006b) of a drug delivery system (DDS). The most significant difficulty, industrially speaking, is the routine manufacture of a product and its profile, given variabilities and extremes of thermal and mechanical processing and resultant changes in surface chemistry and composition (Sarker et al., 1999; Sarker, 2005b).

An emulsion (derived from the Latin

mulgeo and/or Ancient Greek αμ

λγω (

amelgo): terms for milk, which is an emulsion) is a mixture of unmixable, immiscible or in principle unblendable fractions. It implies a discontinuity and heterogeneity on a microscopic (nanoscopic) scale. In classic terms, both phases are usually liquid, but this can be challenged in a plethora of common forms. The two phases can be entwined in the form of a crude ‘amalgam’, as in a depot (as with many liquid phases) of transdermal patches, of a colloidal particle (e.g. micelle), as in a microemulsion, or microheterogeneously, as in the case of a fine emulsion (cream, lotion, ointment). However, it is also the case that both the interior of a normal micelle and the bilayer leaflet of a vesicle represent a phase in which water is immiscible but apolar conjugated, aromatic or lipophilic molecules are miscible. The dispersion (see Section 2.1.1 and 2.3.1) is aided by inclusion of an emulsifier (emulgent, surfactant, etc.), which helps mixing and dispersion (Becher, 2001).

In order to make scholarly and industrial use of emulsions, the right level of background in physical chemistry and the theory of emulsion formation and stability are important, providing understanding of emulsion behaviour and the construction of effective DDSs. Critical considerations for medicinal formulations are: safety, efficacy, dose, hygiene, consistency, purity, quality, reproducibility, toxicity, effects, impurities and extraneous matter, cost, legal compliance, supplier reputation (for the fabrication) and the finished form.

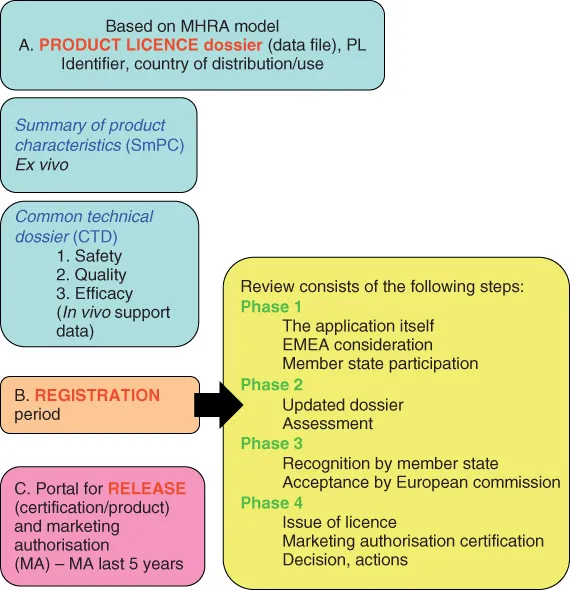

All new emulsion products must pass through a regulatory process as just outlined. Figure I.1 shows a summary of the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regulation process for the approval of a new dispersion drug dosage form. Other regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), also demand presentation of satisfactory safety and efficacy data (the presentation form may, however, change).

A drug product receives approval based on a product licence (PL or marketing authorisation, MA) dossier. Here the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) includes, for example, descriptions of the drug, the routes of manufacture and the physicochemical characteristics (ex vivo) of the molecule, batch information and stability testing information. In humans, the new chemical entity (NCE, candidate molecule) becomes known as an investigational new drug (IND), as presented in the common technical dossier (CTD). The absolute content of the CTD changes between different global regulators, but all CTDs contain information on the human response to the molecule and are responsible for chronicling the clinical evaluation in three tiers of increasingly complex (scrutiny, complexity, modelling, testing, severity and reliability) studies. The central aim of the clinical trials is to prove the product's quality (purity and consistency), based on toxicology and other in vivo tests. This then permits the IND to pass on to a new drug (product) application (NDA) and terminate development, proceeding to product registration and subsequent release.

The PL (or MA) is customarily granted for five years (Sarker, 2008).

![]()

Chapter 1

Historical perspective

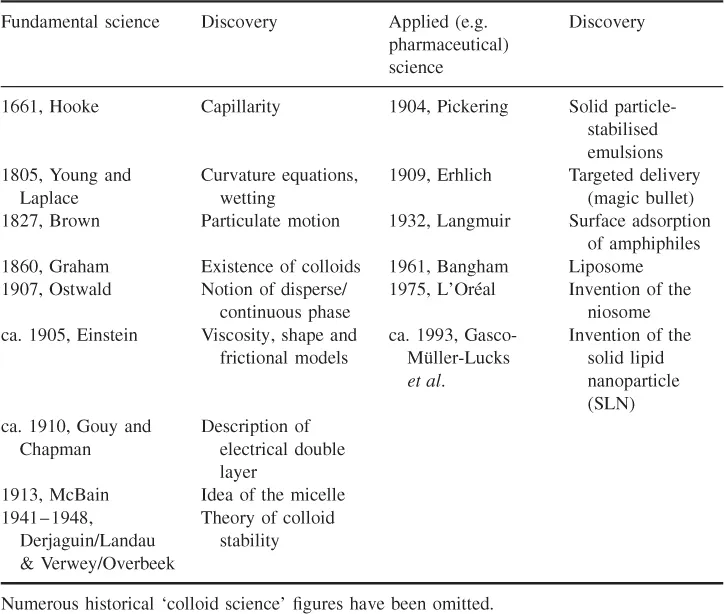

Emulsions in various guises have been around since the dawn of time (e.g. mammalian milk, opal gemstones). What we describe as an ‘emulsion’ is today a very measured and well-understood entity (Becher, 2001), as a result of a chronology of profound and insightful scientific discoveries (see Table 1.1) and industrial practices (Valtcheva-Sarker et al., 2007; Sarker, 2010). Some very ‘big’ names feature in the list of events behind ‘emulsion’ and associated colloid (nanotechnology) science (Gregoriadis, 1973, 1977; Sarker et al., 1999; Pashley and Karaman, 2004; Sarker, 2009a,b, 2012a).

Table 1.1 Historical landmarks in the development of the fundamental and applied sciences relevant to the manufacture and use of ‘pharmaceutical emulsions’

1.1 Landmarks

These are largely definable b...