eBook - ePub

Computational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behavior in Social Dilemmas

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Computational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behavior in Social Dilemmas

About this book

Computational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behaviour in Social Dilemmas shows students, researchers, and professionals how to use computation methods, rather than mathematical analysis, to answer research questions for an easier, more productive method of testing their models. Illustrations of general methodology are provided and explore how computer simulation is used to bridge the gap between formal theoretical models and empirical applications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Computational Approaches to Studying the Co-evolution of Networks and Behavior in Social Dilemmas by Rense Corten in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mathematics & Probability & Statistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Our social environment influences much of what we do. To be more precise, individual behavior is often influenced by the social network surrounding the individual. For instance, when we form an opinion about a political issue, we are likely to be influenced by the opinions of our friends, family, and colleagues and likewise, we influence them.

Much sociological research has been devoted to showing how various forms of social influence shape individual action (Marsden and Friedkin 1993). However, social networks are not always rigid structures imposed on us. Often, we have considerable control over our own social relations. Returning to our example, we may be influenced by our friends when forming political opinions, but we are also, to a large extent, free to choose our own friends. Moreover, it is likely that our decisions in choosing friends are in part related to those same opinions. Thus, social networks and the behavior by individuals within those networks develop interdependently or, in other words, co-evolve. What social network structures should we expect to emerge, and how will behavior be distributed in those networks? In a nutshell, this is the general type of problem this book is concerned with. The example of political opinions is one in which social networks and individual characteristics co-evolve and the same holds for many other types of opinions and behavior. This book focuses on the co-evolution of networks and behavior of a particular kind, namely, behavior in social dilemmas.

1.1 Social dilemmas and social networks

Broadly speaking, a social dilemma is a social situation in which individually rational behavior can lead to suboptimal results at the collective level. We encounter many social dilemmas in daily life. For example, when two researchers are working on a joint project, each might be tempted to let the other person do the majority of the work while profiting equally. However, if both follow this reasoning, the project will never get done, and there will be no profit at all. Similarly, if there is a rumor that a bank might go bankrupt, it is perfectly rational for every individual client to go to the bank and try to withdraw his or her savings. However, if all clients do this, the bank will indeed go bankrupt, and most clients will lose their savings. Another social dilemma arises when a group of people want to participate in an event, say, a protest demonstration. For each participant, it is only worth going to the demonstration if others are going as well. By attending, one runs the risk of being the only participant, in which case there will be no demonstration and one will have wasted one's time. Given this risk, it might be wise to stay at home, in which case the demonstration will indeed not occur.

The situations described above have in common that if individuals try to obtain the most favorable outcome for themselves and behave rationally, the result might be that collectively everyone is worse off than they could have been. In other words, we find a conflict between individual rationality and collective rationality (Rapoport 1974). Using the terminology of game theory,1 we can define a social dilemma more formally as a situation (game) that has at least one Nash equilibrium that is Pareto-suboptimal.2

While all of the examples above can be classified as social dilemmas in this sense, there are also some differences between them. Roughly speaking, the first two examples can be described as cooperation problems, and the third example can be described as a coordination problem. While other types of social dilemmas exist, we only focus on coordination and cooperation problems in this book.

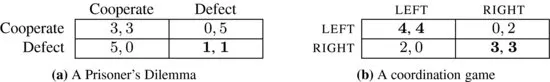

The crucial characteristic of cooperation problems is that although the actors involved can benefit from cooperation, they have an incentive to take advantage of each other, which leads to suboptimal outcomes at the collective level. A game-theoretic model for such situations is the famous Prisoner's Dilemma (see Figure 1.1a). In this game, each player has two options: cooperation or defection. The players’ payoffs associated with each combination of actions are represented as numbers in a matrix. The actual numbers in Figure 1.1 a serve only as an illustration. The relation between the payoffs is what matters. In this game, both players are tempted to play “defect” because this will lead to a higher payoff regardless of what the other player does. If both players defect, they will both earn only 1, which is suboptimal because both could have earned 3 if they had cooperated. However, game theory predicts that goal-directed players will defect because mutual defection is the only Nash equilibrium. Clearly, this equilibrium is suboptimal.3

att voffset="-6pt"? Figure 1.1 Two social dilemma games. (a) A Prisoner's Dilemma; (b) A coordination game.

The Prisoner's Dilemma has become the archetypical social dilemma in the literature and has motivated a vast amount of research. It is typically associated with the problem of social order, which has to do with the questions of why people cooperate even when they have incentives to exploit each other and why society does not collapse into a “war of every man against every man” (Hobbes, [1651] 1988). The Prisoner's Dilemma has been used to model a wide range of social phenomena, including the production of public goods (e.g., Heckathorn 1996), social exchange (Hardin 1995), and the emergence of social norms (e.g., Ullmann-Margalit 1977; Voss 2001).

In coordination problems, the dilemma is of a different nature. Figure 1.1b shows a coordination game (the labels “LEFT” and “RIGHT” in this game are arbitrarily chosen and have no further substantive meaning). In contrast to the Prisoner's Dilemma, the coordination game no longer demands that to maximize his or her payoffs the player should always perform the same action regardless of what the other does. Rather, each player prefers to perform the same action as the other player, that is, to coordinate. Players do not have incentives to exploit one another, but there are incentives to try to work together. Thus, game theory predicts that either both players will play LEFT, or both players will play RIGHT. Once the players have established one of these equilibria, they have no incentive to deviate as long as the other player does not deviate. In this sense, we can consider equilibria in coordination problems as conventions (Lewis 1969).

In so-called pure coordination games, actors have no preference for one convention over the other, but this is not the case in Figure 1.1b. If both players play LEFT, they both earn more than if they both play RIGHT. Therefore, the equilibrium (LEFT, LEFT) is the efficient equilibrium, also called the payoff-dominant equilibrium (Harsanyi and Selten 1988). At first sight, it may seem obvious that if the players simply play LEFT, the social dilemma is solved. This game, however, also involves an element of risk. If the row player plays LEFT and the column player plays RIGHT, the outcome is suboptimal for both. However, the burden of the suboptimal outcome is not distributed equally among the players—the column player still earns a payoff of 2, whereas the row player earns nothing. Given that the row player does not know in advance what the column player will do, playing LEFT is risky. In fact, if the row player assumes that it is equally likely that column player will play LEFT or RIGHT, the expected payoff of playing LEFT is lower than the expected payoff of playing RIGHT. The same reasoning holds for the column player. This equilibrium (RIGHT, RIGHT) can be classified as the risk-dominant equilibrium (Harsanyi and Selten 1988) because it has less risk.

Although the situation in which both players play LEFT is the efficient equilibrium, it is also the equilibrium with greater risk, and it is therefore not trivial that players will play this equilibrium. This feature makes this game especially interesting for analysis as a social dilemma (Kollock 1998). Another reason to classify this game as a social dilemma is that the mixed equilibrium (in which the players play each action with some probability) is also inefficient (Harsanyi 1977).

Coming back to one of the examples above, every potential participant of a demonstration would rather join a successful demonstration than stay at home. However, if everyone else stays home, he or she would rather stay home too. In the case of a coordination failure (some come to the demonstration and some stay home making the demonstration a failure), the outcome is worse for those who did come to the failed demonstration than for those who stayed home. Many forms of collective action share this feature (Hardin 1995).

Although coordination problems have received less attention in the literature on social dilemmas than cooperation problems, applications in real life are abundant. The analysis relates to many types of conventions, such as etiquette (Elias 1969), standards of speech, or technological standards (e.g., choice of computer operating systems or GSM frequencies). Generally, the coordination game can be used as a game-theoretic model of social conformism whenever actors have strategic reasons to align their behavior. Moreover, it can be argued that many social dilemmas that are commonly viewed as Prisoner's Dilemmas could be more fruitfully analyzed as coordination games (Hardin 1995; Kollock 1998). One could say that the value of the coordination game as an explanatory model has been underappreciated in comparison with the enormous amount of attention that the Prisoner's Dilemma has received (Kollock 1998).

Nevertheless, both dilemmas have been studied extensively in political science, psychology, economics, and sociology (as well as in the life sciences, particularly in the case of the Prisoner's Dilemma). The main question in these studies is, under what conditions will actors behave in such a way that they obtain the socially efficient outcome? Social networks can play an important role in answering this question.

1.1.1 Cooperation and social networks

There are different types of answers to the question of why people cooperate in situations such as in the Prisoner's Dilemma. The first type of answer looks for the solution at the individual level and challenges the assumption that people only care about their own payoffs. Proponents of this approach argue that people cooperate because they are motivated by fairness considerations (Rabin 1993) or inequity aversion (Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Kolm and Ythier 2006).

Another approach does not abandon the assumption that people are selfish, but instead looks for social causes of cooperation—social conditions that provide individuals with incentives to cooperate in social dilemmas, even if these individuals only care about their own payoffs. One particular source of such incentives is that cooperative relations often do not occur in isolation but are embedded in a social context (Granovetter 1985). Such “embeddedness” may take several forms. As argued by Axelrod (1984) and others (Taylor 1976, 1987), cooperation may emerge if actors interact repeatedly. This type of embeddedness is referred to as dyadic embeddedness (Buskens and Raub 2002). The prospect of a long-term relationship with the same partner may persuade actors to cooperate on the condition that others cooperate as well.

A second type of embeddedness exists in social networks and can be referred to as network embeddeness (Buskens and Raub 2002; Granovetter 1985). This occurs when interactions are part of a larger network of relations. The presence of third parties further increases the interdependence between interaction partners as compar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- WILEY SERIES IN COMPUTATIONAL AND QUANTITATIVE SOCIAL SCIENCE

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Consent or conflict: Co-evolution of coordination and networks

- Chapter 3: Cooperation and reputation in dynamic networks

- Chapter 4: Co-evolution of conventions and networks: An experimental study

- Chapter 5: Alcohol use among adolescents as a coordination problem in a dynamic network

- Chapter 6: Conclusions

- Appendix A: Instructions used in the experiment

- Appendix B: The computer interface used for the experiment

- Index