![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to the Process of Internal Erosion in Hydraulic Structures: Embankment Dams and Dikes 1

1.1. Introduction

The first part of this book presents the initial results of the National Project ERINOH (the acronym for Erosion Interne des Ouvrages Hydrauliques, i.e. Internal Erosion of Hydraulic Structures) and this chapter provides a general introduction to the problem. What is this lesser known pathology that can seriously damage the safety of such hydraulic structures as embankment dams, dikes, and canals? So far, there has been a strong imbalance in the way academics have presented the physical phenomena that govern the maintenance of hydraulic structures.

Relevant textbooks place the emphasis on the mechanical analysis of general stability, although stability is only marginally involved in the majority of incidents and failures. Consequently, this chapter aims to provide several basic elements that are necessary to understand and analyze the complex hydraulic phenomena that, under changeable circumstances, bring into play the interactions between water and porous media. The main objective of this chapter is to render familiar the knowledge we have obtained so far, thus offering a more global and easier reading of the chapters that follow.

1.2. The significance of internal erosion for hydraulic structures

1.2.1. The set of hydraulic structures in France

France disposes of a significant stock of hydraulic structures. The linear lengths of dikes are roughly equivalent to 13 times the largest dimension of its territory, with more than 9,000 km of protection against flooding, 8,000 km of dikes for navigation canals, and 1,000 km of hydroelectric canals. The number of small embankment dams, whose height does not surpass 15 m, is around several tens of thousands, while the number of large dams approaches 600.

While the first characteristic of French hydraulic assets is their amplitude, the second characteristic is their age: most dikes are more than 100 years old and most dams are older than half a century. Finally, the predominance of natural materials used in the backfilling of these dams is the third characteristic.

The maintenance of such a wide patrimony, both old and built with local materials, requires a costly and decentralized upkeep, which is difficult to achieve in an economically restrictive context. This, in turn, poses a problem for exploitation safety, and hence the need for innovative and economical solutions.

Hydraulic structures are civil engineering structures whose function is to retain or transport water. Apart from being a natural resource, water is also a kind of “fluid” energy. Because it stands in the way of the water, a hydraulic structure must constantly fight against this energy, which can take advantage of the slightest fault in order to break loose. Consequently, following the example of the International Commission On Large Dams (ICOLD), we have regarded the loss of this main function of the hydraulic work as a failure.

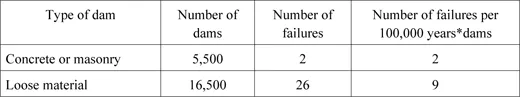

1.2.2. The vulnerability of hydraulic structures

The dams are either built of natural materials without using any binder (backfill) or of materials that are reinforced using hydraulic binders (i.e. lime in the first gravity dams that were built using masonry, and then cement, fly ash, or slag cement in the case of concrete dams). The statistical data gathered by the International Commission on Large Dams (1995), presented in Table 1.1, emphasizes the fact that backfill dams make for more vulnerable structures than concrete or masonry dams. However, this table does not include the more fragile backfill dams that make up the flood-protection dikes whose failures hit the headlines during large floods.

1.2.3. Erosion as a leading cause of failure

Water is the main load as well as the main aging factor that the facility must hold against throughout its exploitation. Without maintenance, the weathering of its watertightness or a massive flood can easily trigger the failure of the entire hydraulic facility.

The forces that traverse the facility either go through the solid phase, in the form of intergranular stress forces (also called effective stress forces), or go through the liquid phase, i.e. water. Water, in turn, can either be found in a permanent and isotropic form, i.e. hydrostatic pressure, or in a transient and anisotropic form, i.e. hydrodynamic pressure. Consequently, there are two types of forces that are fundamental in every abnormal motion, which can trigger two types of completely different failures:

– a global mechanical shearing that separates the grains through tangential intergranular forces that are too elevated, throughout the entire sliding surface, called sliding or general instability;

– a local pullout of the grains, triggered by the hydrodynamic forces of the water, here called erosion and sometimes referred to as local or internal instability.

There are two criteria for the application of hydrodynamic forces; this chapter is only concerned with the first criterion:

– the seepage flow that causes internal erosion;

– the stream flow that can be found on the surface of the porous medium, which produces external erosion.

To get a more precise idea about the relative significance of each of these erosions, it is useful to refer to the statistics compiled by Foster et al. [FOS 00] regarding large dams. The following table shows that erosion (whether internal or external) represents the greatest danger, being far ahead of the problem of stability against sliding phenomena. Of the failures, 94% are caused by erosion. Over time, the failure probability for backfill dams has decreased, but the relative significance of erosion among the causes of failure has increased (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Relative significance of failure modes (ICOLD 1995, excluding China)

| Modes of failure in large dams | Number of failures to number of dams ratio in 1970–1979 | Number of failures to number of dams ratio in 1980–1989 |

| Internal erosion | 20 × 10–4 | 16 × 10–4 |

| External erosion | 26 × 10–4 | 19 × 10–4 |

| Sliding | 4 × 10–4 | 1 × 10–4 |

Although it is less known, internal erosion by no means is less dangerous, as is shown by the recent surveys on the failure of large dams.

1.2.4. Internal erosion: one failure per year in France

Internal erosion has been targeted as a recurrent maintenance problem. The first European symposium of ICOLD in 1993 confirmed that internal erosion is a major concern at international level, thus requiring a European research team to work on such issues. Soon after, the flooding of the Rhône in October 1993 and January 1994 caused 16 breaches in the dikes of the Camargue. The investigations carried out by Cemagref identified the internal erosion as the only cause. Following this incident, the French Committee for Large Dams (CFGB) appointed a team of researchers from the relevant field to collect feedback. The team submitted their report on the typology, detection, and repair of disorders caused by internal erosion, which was then distributed at the ICOLD Congress in Florence in 1997 [FRY 97]. The team identified that from 1971 to 1995, 71 incidents, of which 23 failures, had been reported on 550 large dams, several thousands of small dams, and 1,000 km of dikes. This study did not take into account the flood-protection dikes or the navigation canals.

Despite this publication, the frequency of failures remained high and constant during the following years, that is approximately one failure per year: the failure of the Arroux gutter in 2001, the Ouches dam in 2001, the Briare canal at Montambert in 2002, the North canal in 2003, the Rhône-Rhine canal in 2005, and the Roanne canal at Digoin in 2007. The most significant water damage took place at the time of the great floods in the Lower Rhône. The breaches of the Gard flood on 9 September 2002 cost the lives of five people in the village of Aramon and caused damages of € 1,200 million. The following year, when the Rhône flood took place in December 2003, more than 100 points of disorder were noted, of with half a dozen breaches, causing €845 billion in damages, spread over five déparments. More generally, in Europe, the yearly cost of floods between 1980 and 2003 was estimated at three billion dollars. In France, it reached a billion euros in 2002 and 2003. The vulnerability of these structures is such that a decrease of only 1% in these damages would be enough to justify the profitability of a research project on internal erosion, whose predicted annual gains should be clearly higher.

1.3. The impact of incidents on embankment dams and dikes

1.3.1. Terminology

In what follows, we will adopt the definitions given by the ICOLD as well as the most recent definitions given by French regulations.

An embankment dam is a facility that retains a permanent body of water (and is thus considered to be a hydroelectric canal or a navigation canal). A dike is a facility that retains the water only temporarily (i.e. flood-protection dike).

A failure is a collapse or a displacement of the entire backfill dam or of the foundation of the facility so that the water can no longer be retained by the facility.

A dam accident is a collapse or a displacement of the backfill dam that, in the absence of immediate intervention, can lead to failure.

A failure mode is a breaching process generated by a generic type of force. We can d...