![]()

Chapter One

Theory and Architectural Technology

Norman Wienand

Department of Architecture and Planning,

Sheffield Hallam University, UK

Why theory, what has theory got to do with architectural technology and why worry about it? One answer suggests that it needs a differentiating design theory to reinforce its position as the primary technical design authority in the modern construction industry. In saying that, however, it also raises a whole host of further questions such as what is technical design, what position is being referred to exactly and why a differentiating design theory? This chapter is placed at the beginning of the book because it poses some of the principal questions that need to be addressed as the subject of architectural technology develops into a mature academic and professional discipline. Considering architectural technology historically in terms of alternative theories, through theories of technology and also by means of complementary design theories, allows the reader to reflect on architectural technology in its many expressions, be they historical, physical or even metaphysical. In addition, simply establishing and documenting its existence, confirming a theoretical and historical foundation to the discipline, permits continuing deliberation and development, providing a focused context for further relevant research.

Introduction

Why do we need a theoretical approach to architectural technology? Firstly, to answer this question we need to have some understanding of what we mean by theory. The Concise Oxford Dictionary offers three enticing descriptions:

- the sphere of abstract knowledge or speculative thought,

- exposition of the principles of a science, etc.,

- collection of propositions to illustrate principles of a subject.

While the last two can have a significant role to play in many aspects of architectural technology, particularly those related to building physics and architecture generally, it is primarily the first, speculative thought, that gives us the catch-all definition we require, namely theory as ideas as opposed to practice and theory as thinking rather than doing. Most practising technologists, however, will know intuitively that all doing is preceded by thinking and sometimes very long and hard thinking. Calling it theory (e.g. this is all very well in theory but how will it work in practice?) simply gives us a framework and space to structure our thoughts.

Therefore a theoretical approach is already tied to many aspects of the practice of architectural technology but is particularly closely related to its existence as an academic discipline and how we take the subject forward in a controlled and managed way. In academic language, architectural technology is a vocational subject, meaning it is intended to lead on to practice as a professional. This is different to more academic disciplines where there is no closely related occupation. However, even vocational subjects need to be established as having strong academic principles or they exist merely as training programmes. Architectural technology now functions as both a professional discipline and also as an academic discipline and, as with most vocational subjects, these two aspects are very closely aligned (Wienand, 2011a). Although it may be possible to exist as a professional discipline without academic support, architectural technology is now predominately a degree level entry profession. It is taught as an academic subject throughout the UK and is supported by significant areas of research, all hallmarks of an established academic discipline. That is quite an achievement for a discipline of such comparative youth, and the next requirement is to bring what is a wide ranging research base into some form of recognisable arrangement.

This observation leads nicely on to the next set of questions, namely: why research, what is it aiming for, what exactly is architectural technology research, what for that matter is architectural technology? These questions can continue with: is architectural technology just detailing or is it technical design in architecture or perhaps much more than that, and what exactly are architectural technologists?

Leaving the research questions to others for now, we still have to ask: what is technology, what is theory, and therefore what is architectural technology; and what about theories of technology? All of these questions are fundamental to understanding the discipline of architectural technology and theorising allows us to consider these questions and many more in an attempt to provide a stable academic foundation for this exciting and immensely rewarding discipline.

Why we need theories

The concept of theory comes in many forms, from the everyday good idea to the verifiable scientific theory that takes on the mantel of ‘fact’ until proven conclusively otherwise, using scientific method. What they are all about, however, is ideas, and that is precisely why we need theories. Theorising can just be about ideas, making us think and see things in a different way, leading potentially to new innovative ideas. Essentially, though, it is about providing a structure to our thinking and a framework for our conclusions. For the discipline of architectural technology, viewed from either the academic or professional perspective, theories also allow us to use that framework to give some meaning to the past, the present and, in particular, the future. By taking that open and variable philosophical interpretation of what we mean by theory, we can use the simple form of ‘ideas’. In this abstract or speculative sense, the strength of ideas comes from their very nature and therefore, as concepts, they are there to be considered in depth rather than any notion of being deemed factual.

Why exactly does architectural technology need theory? It could be argued (a theory) that it does not actually need theory and exists quite satisfactorily in its present form. That view suggests that it is a constant task based profession, that once mastered remains static for all time, which is clearly not true. The reality, as we all know, is that keeping abreast of change is a vital function of the practising architectural technologist, which leads us to two further questions: how does theory help us master change and, more fundamentally (we keep coming back to this), what exactly is architectural technology? The rest of this chapter attempts to confront this dilemma by using the concept of theorising to provide routes to the answers. For example, understanding how the discipline has got to the position where it exists today will help to provide some insight into what exactly it is. A deeper theoretical understanding of what architectural technology actually is may also help us to understand and grasp the present, predict the future and maybe also allow us to define that future.

Historical perspectives – learning from the past

The claim that theory can help us to understand how we got to where we are and therefore to understand who we are comes with the study of architectural history, and in particular the aspects of architectural theory that place philosophical thinking in distinct historic periods. It is recognised that the constantly evolving world of construction is not a smooth flow from one new idea to another but that just as with biological evolution it moves in a haphazard way, responding to whatever external influences are at play at any one time.

While architectural technology as a professional discipline has much in common with many allied vocational disciplines, such as civil and architectural engineering, building and quantity surveying, service and environmental engineering, it is probably closer to mainstream architecture than any other, especially when viewed from the perspective of the layperson. It can be argued that a study of the shared history of the two disciplines is where the subtle but real differences emerge that allow architectural technology to assume a separate and distinct identity. Both professions will see a significant heritage in the concept of the Master Builder that was so important to the buildings of the Middle Ages, or probably more accurately defined as the Gothic period of the 12th to 14th centuries. The comprehensive role of on-site designer, manager, builder and engineer that was the Master Builder would be entirely familiar to both modern day architects and architectural technologists. The collaboration with fellow craftsman, stonemasons and carpenters in the creation of buildings based on verbal communication and full-scale layout in the field would also be instantly recognisable (Barrow, 2004). Historical texts that celebrate the triumphs of the Gothic era tend to focus on the architectural features that made it all possible and in particular the architectural legacy it provided for the history of Western architecture (see Figure 1.1). Few, however, really celebrate the technical mastery, the depth of understanding and the pure technical design genius required.

The great Gothic epoch was only possible because the Master Builders were the ultimate technical designers before all else as the seminal work, Architectural Technology up to the Scientific Revolution (Mark, 1993) makes abundantly clear. Therefore, by taking a slightly different perspective, it is possible to theorise with some authority that the current professional discipline of architectural technology has very firm roots in the Middle Ages and we could be tempted to go even further back. However, by taking this particular moment in history and assuming a common heritage we can also then trace a lineage that supports but equally differentiates architectural technology from architecture.

It does not take long to move from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries), which witnessed a separation of the architectural design process from on-site technical design of construction and as such triggered an elevation of artistic and architectural design, leading eventually to the now familiar role of the modern architect. Other major developments followed as a consequence, such as the need to produce discrete depictions of their concepts; in other words, drawings. The complex philosophy of communication through drawing is interesting and continues to evolve today as new drawing tools and methods become available. The separation that came about in response to the need to impart specific construction information to builders as opposed to a drawing that depicted the final appearance of the building was another factor that helped to define a division between technical and representational illustration. Indeed, it is no surprise that two Renaissance architects, Brunelleschi and Alberti (Edgerton, 2009), are credited with the clear formulation of perspective drawing, a magnificent method for providing a three-dimensional appearance that from a technical standpoint has little use because, as it is ‘not to scale’, it is not possible to transfer dimensions. Again these historical observations can be used to support a theory that this division of drawing styles helped to precipitate another divergence between the two professions, with technical drawing traditionally the realm of the architectural draughtsperson having a clear lineage all the way to building information modelling (BIM) and an artist inspired façadism with the concept that creativity can exist universally (Wienand, 2011a).

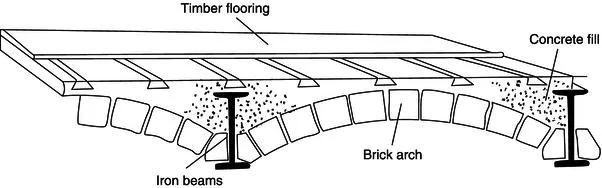

While the architecture of the Middle Ages relied on and celebrated the impact of building technology and technical design on the final built form, the Renaissance delivered major advances in architecture that were not related directly to technology, with some notable exceptions. It was not until the Industrial Revolution that building technology took another major evolutionary surge forward, although this time probably under the command of the engineering profession. The technologies unwrapped during this period allowed the creation of many more wonderful architectural achievements and can also in theory be linked directly to current building design, where much cutting edge architectural design can be claimed to be ‘technology enabled’ (see Figure 1.2).

We have briefly examined distinct historical periods where the impact of technology on the ensuing architecture is markedly different. The Middle Ages was very much constrained and controlled by technical limitations, the Renaissance and beyond saw architectural exuberance unhindered by technical shortcomings and now we have technology essentially driving architectural innovation. Any theoretical exploration of the role of technology in architecture must also examine the role of architectural technology on building and therefore whether it is the ‘technology to build’ or the ‘technology of building’. The answer is clearly both, depending on the circumstances, and is also potentially related directly to the role of an architectural technologist, but the relationship is also a lot more complicated as historic developments illustrate.

In the concluding chapter to his historically significant and remarkably inclusive work, Construction into Design, covering the period from the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution to the latter stages of the 20th century, James Strike (1991) contrasts external drivers on the introduction of architectural technologies such as fashion and war with the spirit of innovation and the potential for failure. He summarises these relationships as involving changing viewpoints, the nature of change and evolutionary themes and in so doing illustrates the apparently capricious world that governs the adoption of new technologies. In discussing changing viewpoints he points to differing views on the value of technology such as ‘one generation reacting against its predecessor’ or straightforward disagreements over the value of industrial technology in the production of architecture – an issue we still struggle with today when using state of the art technology to produce retro-styled buildings. The next point, closely related to changing viewpoints, is recognising in the nature of change that humans are slow and unpredictable when it comes to accepting the value of things new. Here Strike demonstrates this with the considerable time lags between the inventions of cast iron (Abraham Darby with smelting iron in 1709) and concrete (Joseph Aspdin with Portland cement in 1794) and their eventual use in building, let alone enthusiastic adoption. He also points to a discernable pattern in suggesting that: ‘the story line for each material or technique is never identic...