![]()

Section 1

Introduction

![]()

1 The past, present and future of adaptation: setting the context and naming the challenges

JEAN PALUTIKOF1, MARTIN PARRY2, MARK STAFFORD SMITH3, ANDREW J. ASH3, SARAH L. BOULTER1AND MARIE WASCHKA1

1 National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Griffith University, Australia

2 The Grantham Institute for Climate Change and Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, UK

3 CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship, Australia

1.1 The purpose of this book

This book seeks to expose and debate key issues in climate change adaptation, and to report the current state of knowledge on adaptation. Adaptation is often the poor cousin of the climate change challenge – the glamour of international debate in metaphorically smoke-filled rooms is around mitigation, whereas the bottom-up activities of adaptation carried out in community halls and local government offices are often overlooked. Yet as international forums increasingly fail to deliver against mitigation targets, the realisation is dawning that effective adaptation will be essential across all sectors to deal with the unavoidable impacts of climate change.

Many challenges surround the definition and implementation of successful adaptation, which this book seeks to address. To explore these challenges, we have taken a selection of papers from the First International Conference on Climate Change Adaptation ‘Climate Adaptation Futures’, held on the Gold Coast, Australia, in June 2010. This three-day meeting of over 1000 researchers and practitioners in adaptation was the first of its kind.

What are these challenges? We begin this chapter with a discussion of five principal challenges for adaptation. We then outline the content of this book. We map the chapters of the book onto the five challenges, so that those who wish to explore in greater depth can do so.

1.2 What are the five principal challenges for adaptation today?

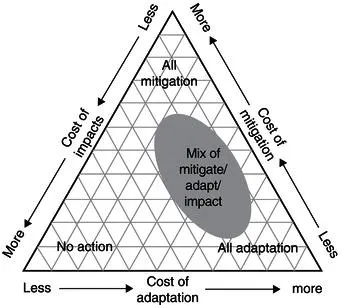

1.2.1 Challenge 1: Understanding the balance of actions to adapt and actions to mitigate

We tend to assume that the wisest course of action in confronting climate change involves a mix of two actions: (a) reducing emissions as much as we can afford so as to keep impacts and adaptation costs to the minimum over the long term, (b) adapting to most of the remaining impacts so as to minimise damage to society and the environment. Then, thirdly, we bear the costs of the unavoidable residual damage (which includes impacts that we cannot adapt to or we judge not worth adapting to). Figure 1.1 is a schematic of the trade-offs between these three with, in the example shown, the mix being located to the right of the triangle, the predominant actions being roughly equal amounts of mitigation and adaptation, with less being spent on remedial damage. A less optimistic picture (more ‘realistic’ say those dismayed at the slow progress of international climate policy) would be to locate the mix of actions more to the left of the triangle, with less action on mitigation and adaptation leading to more damage from impacts.

Schemas such as this suggest that we know the relationship between action and outcome, whether it be mitigation or adaptation. In theory we might, but in practice we do not. Even if we did, it is not clear whether an ‘optimal’ mix of actions exists even in theory (i.e. one where actions along each of the three lines give the most reward). However, this schema is a fair reflection, in outline, of how our current actions are premised: that if we take one line of action we will ultimately reduce costs along another. If this is the case, what task is being left to adaptation given the current effort (and expected outcome) from mitigation?

Adapting for ‘overshoot and recover’

It is widely accepted that the threshold for dangerous climate change is a warming of 2 °C above pre-industrial levels. It is increasingly unlikely that emissions of greenhouse gases can be held at a level that will ensure global temperatures remain below this threshold (Rogelj et al. 2011): it would require stabilisation at about 450 ppm CO2 equivalent (CO2e) and we are already at 430 CO2e. Therefore, we need to explore scenarios in which atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, and possibly even global temperatures, overshoot their targets and then recover to stabilise below dangerous levels.

Since the 2007 Fourth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), partly in response to gaps in the Assessment and also driven by the need to answer urgent questions from policymakers, a number of analyses have been completed of the climate outcomes for varying strategies of emissions reductions (e.g. Hansen et al. 2008; Van Vuuren et al. 2008; Allen et al. 2009a; Meinshausen et al. 2009; Parry et al. 2009b; Schneider 2009; Sanderson et al. 2011; Tomassini et al. 2010).

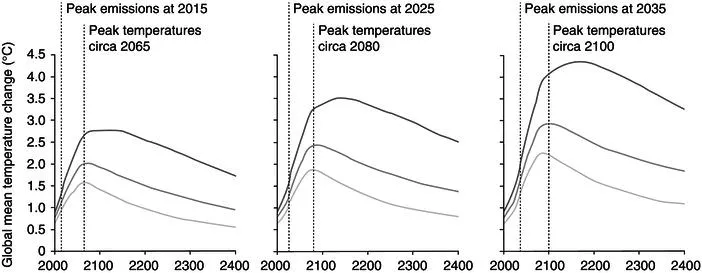

Figure 1.2 shows the projected global temperature increases using a simple Earth-system model (Lowe et al. 2009). Here we assume that rates of global emissions, which are currently increasing at about 3% per year, are transformed to a 3% annual reduction. The emissions peak or downturn is at varying dates (Parry et al. 2009b):

- immediate action with an emissions downturn in 2015 would lead to a global mean temperature peak at about 2 °C (above pre-industrial) around 2065

- delayed action leading to an emissions downturn in 2025 gives temperature peak at about 2.5 °C around 2080

- a further delay in action with a 2035 downturn points to peak temperatures at about 3 °C around 2100.

Calculations such as these (and there is broad agreement among the estimations referenced above) led to the view voiced at the Copenhagen summit in 2009 that almost immediate action was needed to avoid warming by more than 2 °C (Allen et al. 2009b).

It was agreed at the 2011 Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Durban, that action will not be immediate but is planned to be implemented by 2020 – and will still be intended to avoid exceeding 2 °C warming. To achieve this would require more substantial emissions reductions, levels which many find difficult to envisage (Anderson and Bows 2011; New et al. 2011).

The likelihood, from the analysis above and others similar to it, is that we will exceed 2 °C of warming, and realistically we should be planning to adapt to at least 3 °C. We should assume that very substantial adaptation will be needed, in combination with an annual 3% per annum emissions reduction over two centuries (i.e. until 2200). This would bring global temperatures back to about 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels by 2200 and 1.0 °C by 2300, a state advocated by some as being the highest temperature at which the biosphere could be sustained over the long term (Hansen et al. 2008).

The adaptation ‘need’ implied by mitigation

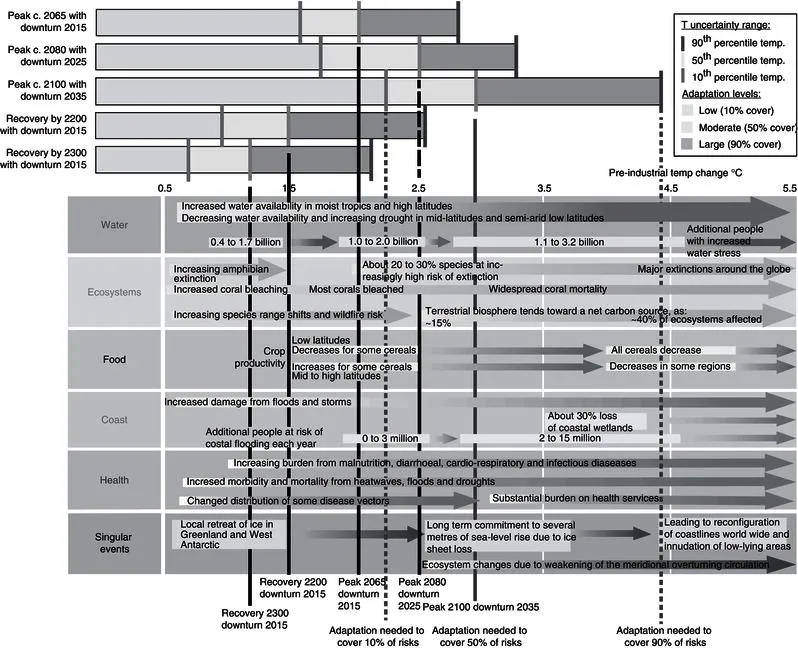

As discussed with respect to Figure 1.1, there is a balance to be achieved between adaptation and mitigation. Thus, even if we are successful at limiting warming to just 1.5 °C through mitigation, we will still have to adapt to the impacts we have failed to avoid. This concept is explored further in Figure 1.3.

When the climate outcomes discussed in the previous section are superimposed on the table of impacts from the 2007 Working Group II Fourth Assessment of the IPCC (Parry et al. 2007, Table TS.3), as shown in Figure 1.3, we can explore the impacts avoided (or not) by mitigation, as well as the amounts of adaptation needed to keep residual impacts to an acceptable level. The vertical lines represent projected median temperature outcomes, so that impacts to the right of the lines are as likely as not to be avoided by mitigation, and vice versa for impacts to the left. The area to the left is thus the ‘adaptation field’, the area of potential impacts that either must be borne or adapted to.

From Figure 1.3, we can see that, even assuming the strongest possible mitigation action (giving an even chance of exceeding 2 °C) the potential impacts are substantial; for example, 1 to 2 billion people are estimated to become short of water. The consequences for delayed or reduced action can also be inferred from Figure 1.3.

There is a substantial range of uncertainty surrounding the temperature outcomes for different courses of mitigative action, shown by the upper horizontal bars in Figure 1.3, and these represent a major challenge for adaptation. Since adaptation costs increase steeply, sometimes even quadratically, with climate change there are difficult decisions to be made about the extent of cover to plan for.

In Figure 1.3 we assume that high levels of adaptation are needed to cover 90% of impacts, moderate levels of adaptation would cover 50%, and low levels would cover only 10% of impacts. On this basis, for example, if global emissions did not peak until 2035 and if we wished to cover 90% of expected impacts, then we should be planning to adapt to at least 4 °C of warming.

The challenge left to adaptation by the UNFCCC

What does the analysis so far imply in terms of what has been achieved by the UNFCCC? The accords achieved so far in the UNFCCC process call for all countries to commit to emissions reductions to avoid a global temperature rise of more than 2 °C, and aim to mobilise US$100 billion annually by 2020 for developing countries to fund mitigation and adaptation (UNFCCC 2010).

The pledges put forward by nations so far have, for the most part, been accepted domestically – with one notable exception. The US promise to cut emissions to 14–17% below 2005 levels by 2020 has yet to be approved by the US Senate and for now remains unconfirmed. The outcome of the current pledges, both those officially announced and those under consideration would, if fully implemented, lead to a temperature peak of 3.5 °C (Hohne et al. 2011).

The funding for implementation by developing countries (adaptation and mitigation) agreed to in the UNFCCC Cancún Adaptation Framework is US$100 billion per annum. Assuming that about one half of this US$100 billion is used for adaptation, this is likely only to address the impacts resulting from 1.5 °C of warming (Parry 2009). The food and health sectors, for example, might be able to adapt and thus avoid impacts of up to a 1.5 °C rise by 2030, the water sector up to a 2 °C rise by 2050 and coasts up to a 2.5 °C rise by 2080 (Parry et al. 2009a). But for ecosystems and some singular events, such as Greenland ice melt, most impacts simply cannot be avoided whatever the scale of funding available.

Consequently there is currently a gap of 1.5 °C between the adaptation covered by present funding targets (1.5 °C) and the mitigation pledged within the UNFCCC negotiations (3 °C). If this gap is not closed the unavoided impacts will likely be substantial. This is shown in Figure 1.4.

Moreover the UNFCCC figures for adaptation (to 1.5 °C) could be substantial underestimates. The financial assistance needed by developing nations may be two to three times higher overall and many more times higher for certain sectors (Parry et al. 2009a). The UNFCCC estimates do not, for example, include any costs for ecosystem adaptation, which alone have been valued at US$65–80 billion annually by 2030 for protected areas and almost US$300 billion annually for non-protected areas (Fankhauser 2010). Even the latter figure covers mainly protection of forests and biodiversity in farmed areas and does not include the ecosystem damage in unmanaged areas that is simply unavoidable, such as the loss of warm-water coral reefs.

To conclude, there are currently plans (possibly themselves underestimates) to fund adaptation to 1.5 °C of warming, but the peak of warming from projected emissions, assuming current efforts on mitigation, is likely to be 3 °C or more. Closing this 1.5 °C gap presents a huge challenge to adaptation.

1.2.2 Challenge 2: Adaptation as transformation, adaptation as incremental change

A key challenge for adaptation is knowing when to adapt and how much to adapt. Humans have always adapt...